This weekend members of Congress will join the crowds flooding the streets of Selma in remembrance of one of the most heinous attacks by law enforcement on civilians in our country — Bloody Sunday. They will shake hands with civil rights leaders, pose for photo ops, attend services and celebrations, but it is uncertain whether they will actually cross the bridge they need to cross. The political aisle remains a bridge too far for some conservative members of Congress to traverse to ensure a meaningful fix to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the crown jewel of civil rights laws ushered in by Bloody Sunday.

RELATED: Obama on why the march isn't over

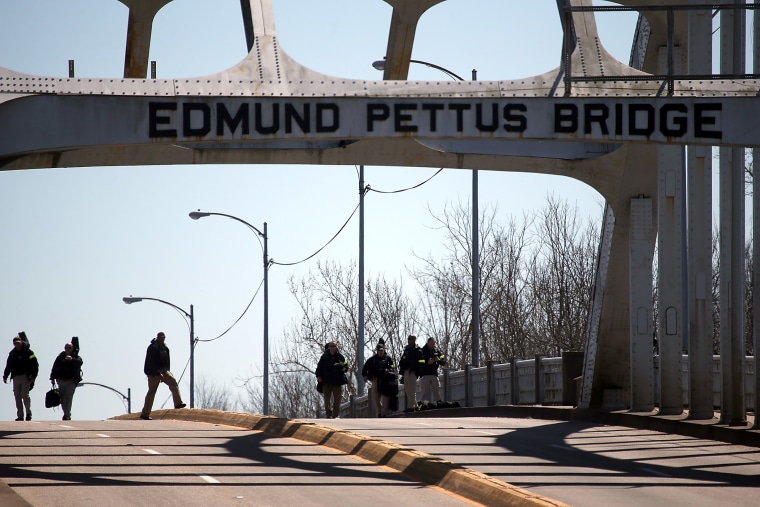

Instead, Congressional representatives and other politicians will participate in a symbolic march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which is named after a former senator, Confederate soldier, and Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. For too many, this weekend’s marches are merely symbolic and, for that reason, an entirely different animal from the original bridge crossing that was orchestrated by Martin Luther King Jr. and countless foot soldiers who led one of this nation’s most transformative democracy movements.

"The political aisle remains a bridge too far for some conservative members of Congress to traverse to ensure a meaningful fix to the Voting Rights Act of 1965."'

The primary goal of the movement was to ensure that African-Americans could register to vote and participate equally in the political process. Voting rights were not just the foundation of political power but also the vehicle to justice. Much like today, the courts regularly did not hold white individuals accountable for taking black lives. This was, in part, because of the composition of juries, which were (and still are) drawn from the pool of registered voters. All-white jurors were loathe to convict law enforcement or other white actors for killing or assaulting blacks.

Thus, the right to vote was not just a political tool, it was a hoped-for lifeline.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which became law just six months after Bloody Sunday, delivered protection of the right to vote and a new equality standard for our democracy. Importantly, passage and reauthorization of the act had enjoyed increasing bi-partisan support — until now. When first enacted in 1965, the House approved the law by a vote of 328-74. When Congress was called to reauthorize the special provisions of the act, it did so with overwhelming bi-partisan support on four separate occasions: in 1970, 1975, 1982, and, most recently, in 2006 with a vote of 98-0 in the Senate and 390-33 in the House.

Congress is being called upon now to support the Voting Rights Act again. In June 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the part of the Voting Rights Act that triggered federal screening of voting changes in jurisdictions with a documented history of virulent racial discrimination in voting. The Court’s decision in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, took away the ability to preemptively challenge some of the most pernicious and retrogressive anti-voter laws before they discriminated against minorities.

Since Shelby, there has been ample and incontrovertible evidence of its discriminatory fallout.

RELATED: Reactions on the ground at #Selma50

Voter ID laws that purport to protect against the statistical ghost of in-person voter fraud are a prime example. In a joint report with the Center for American Progress, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, where I serve as associate director-counsel, documented a sharp decrease in voter turnout in 2014 as compared to the 2010 midterm elections in four of five states studied — Texas, Alabama, North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia. Those four states were formerly covered by the provision of the act that the Court struck down, section 4(b).

In Texas, LDF represented college students who were blocked from using their state-issued student IDs — but not gun-carry permits — to vote in the November elections, despite the district court’s finding that Texas’ photo ID law was enacted with the intent to discriminate against black and Latino voters, two groups that had recently become a record percentage of that state’s electorate.

"Ironically ... because of the Selma’s success, those of us who support stronger protections for voting rights have further to go in convincing Congress of the need for a fix."'

Among other restrictions, North Carolina passed legislation making it harder to vote by slashing seven days of early voting, requiring photo ID, throwing out provisional ballots cast at the wrong polling station, and eliminating same-day voter registration — 40% of day-of registrants were black. Similarly, in Tallahassee, Florida, a polling place serving 90% African-Americans was closed and moved to a new location that was harder to access by public transportation. Officials in Athens, Georgia, considered cutting the number of polling places in half and replacing them with just two early voting centers, which were located inside police stations and would require many voters of color and students to reach via three-hour bus rides. And the list goes on.

Ironically, despite these and countless other examples, because of the Selma’s success, those of us who support stronger protections for voting rights have further to go in convincing Congress of the need for a fix.

To be sure, the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014 (VRAA) which aims to restore the pre-Shelby protections has received support on both sides of the aisle. This makes sense: Every lawmaker — indeed, every American — should support the right to participate in our democracy, regardless of race, language, or class. But is it not enough. The VRAA has yet to be put to a vote in Congress. While the country waits for Congress to act, the right to vote is being chipped away — not with clubs and attack dogs, but with a highly partisan legislative strategy of death by a thousand cuts.

RELATED: Why North Carolina is the new Selma

As Selma’s visitors and residents stand ready for the symbolic crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge this weekend, I hope that Congress will conjure the courage to cross bridges of even greater expanse — those of ideology and politics, recognition and understanding. This should not be a partisan issue. This is about living up to America’s promise to give every person a voice in our democracy. We should be concerned about having more — not fewer — people exercise the hard-fought right for every citizen to vote.

The least that Congress can do is allow the VRAA to reach the floor for a vote. Indeed, every member of Congress in Selma this weekend should openly commit to advance this important legislation in this anniversary year. To do anything less than that — to allow the crown jewel of the civil rights laws to remain disemboweled and hollowed — would be the greatest fathomable desecration of the legacy of Bloody Sunday.

Janai Nelson is associate director-counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.