By any measure, Mario Rubio went to great lengths to vote last fall.

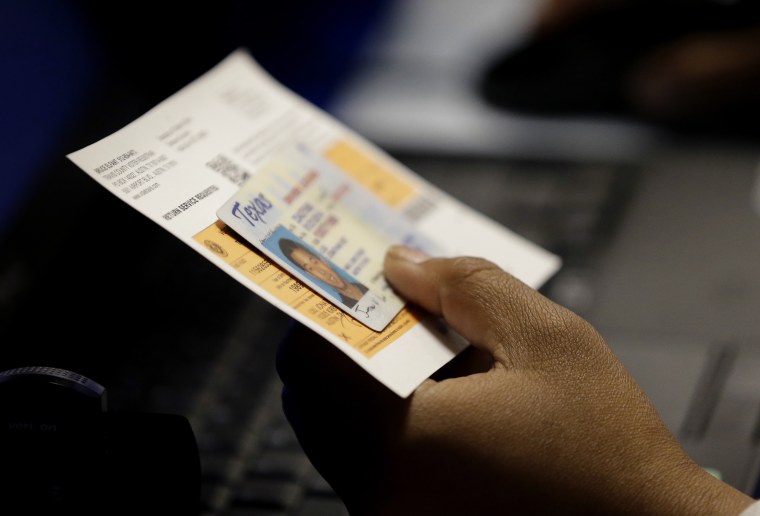

Though he was in a rehab center after developing an infection during surgery, Rubio, a 60-year-old resident of Austin, Texas, asked the facility’s director whether a trip to the polls could be arranged. But he had given his wallet with his driver’s license to his brother for safe-keeping when he went to the rehab center, meaning he didn’t have an acceptable photo identification under the state’s strict voter ID law. As a result, after waiting in a van for over an hour and a half, Rubio was forced to cast a provisional ballot, even though he had plenty of other identification.

A day later, Rubio was transferred to a different facility. But the papers he’d been given telling him where to send a copy of his ID in order to make his provisional ballot count weren’t transferred with him. That left him unable to validate his provisional ballot within the 6-day time frame provided by the law. Rubio later got a letter telling him his vote was thrown out.

RELATED: New study rebuts John Roberts on Voting Rights Act

Rubio is a regular voter—he described himself as an independent who is “semi-conservative”—and he said the experience left him feeling “pissed off.”

“I really went through a lot of effort to vote,” said Rubio, who msnbc located via the Brennan Center for Justice, which, along with the U.S. Justice Department and other groups, is challenging the law in court. “You have to understand, I had just gone through surgery. I wasn’t feeling good, and I was still trying to recoup from surgery, and then I have to wait ninety minutes, two hours in a van—and then my vote doesn’t count.”

Of course, Rubio was far from alone in being stymied by his state’s ID law. It’s impossible to say how many people it stopped from voting last fall, but around 600,000 disproportionately non-white registered Texas voters—and around 1.2 million eligible voters in the state—lack the ID required under the law. (MSNBC spoke to a number of disenfranchised would-be voters last fall, and the Brennan Center has itself publicized several other stories.)

On Tuesday comes the next stage in a years-long battle over the law that may well be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, and could have a major impact on the ongoing national fight over Republican-backed voting restrictions. A three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans will hear Texas’s appeal of a district court ruling last fall that struck down the ID law.

Myrna Perez, a top Brennan Center lawyer who is helping to bring the challenge to the law, said stories like Rubio’s and numerous others that have emerged demonstrate the real harm done by the ID measure.

“This law does not abstractly hurt people,” said Perez. ”This law concretely is making it harder for eligible Texans to be able to vote.”

The law has had a tortured path through the courts up to this point. Passed in 2011 by Texas’s Republican legislature and signed by then-Gov. Rick Perry, it was blocked as racially discriminatory under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act the following year. But just hours after the Supreme Court neutered Section 5 in 2013, Texas announced that the law would go back into effect.

Last October, it was struck down as racially discriminatory under a different part of the VRA, and as an unconstitutional poll tax. In a scathing and thorough opinion, District Court Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos wrote that proponents of the law were motivated “because of, and not merely in spite of,” its detrimental impact on minorities. But weeks later, the Supreme Court issued a one paragraph order blocking that ruling from going into effect, green-lighting the law for use in last November’s election.

The record compiled in the district court trial was damning. A parade of experts testified to the substantial financial and time costs required to obtain an ID. Some voters “have to choose between using their money to buy an ID or something else that may be important to them,” one said on the stand.

And Texas all but acknowledged it had done little to help provide IDs for the huge number of its citizens who lack one. The program it set up last year to provide IDs had given out under 300 at the time of the trial in September.

RELATED: Hillary Clinton has been outspoken on voting rights

Several historians pointed out how the law fit with Texas’s long history of voting discrimination against minorities. And an expert on voter fraud noted that she’d found just four fraudulent votes in Texas since 2000 that the ID law would have prevented.

The case could have a major impact on voter ID laws nationally. Similar laws passed by several other states have been challenged lately. But because of the strictness of the Texas law, and the state’s uncontested history of discrimination, many voting rights advocates see this case as the strongest. They even hope it could lead to a Supreme Court ruling that makes clear that at least some ID laws are so restrictive as to violate the Constitution.

The 5th Circuit is known as perhaps the most conservative appeals court in the country. But the law’s challengers may have been heartened by the news that two of the three judges who will sit on Tuesday’s panel are appointees of Democratic presidents. They also say that as a procedural issue, Judge Gonzales Ramos’s ruling shouldn't be overturned lightly.

“The question that the appellate courts are going to be deciding is whether or not the judge made any decision that was a clear legal error, which is a high standard to meet,” said Perez. “They’re not going to be in a position where they’re supposed to be substituting their judgment over what the district court did.”

Of course, whichever side loses is likely to appeal either to the full court, or directly to the Supreme Court. Ultimately, the right to vote for hundreds of thousands in Texas—and perhaps millions more around the country—may well end up in the hands of John Roberts and co.