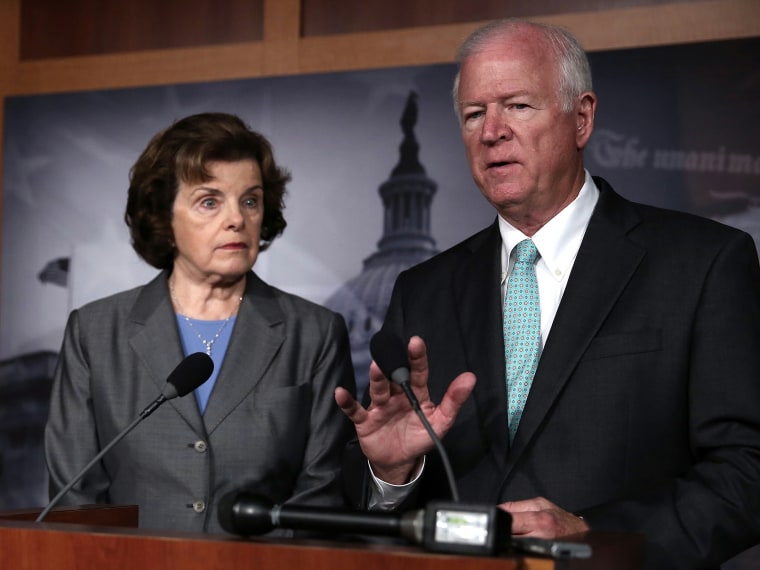

The top senators on the intelligence committee were eager to reassure the public that disclosures about the National Security Agency vaccuming up the communications data of American citizens were nothing to panic about. So Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Saxby Chambliss held a press conference to get the word out that legislators had the issue well in hand.

But some of the actual legislators, such as Maryland Democratic Senator Barbara Mikulski, felt differently."'Fully briefed’ doesn’t mean we know what's going on," Mikulski told Attorney General Eric Holder in a Senate hearing.

A report in the Guardian revealed that the secret court that approves requests for surveillance on suspected foreign agents in the U.S. ordered Verizon Business Network to turn over communications data on its customers in the U.S. to the National Security Agency. The information did not include the content of phone calls or the identity of the customers; it did include time, duration, and the numbers involved of all calls "between the United States and abroad; or wholly within the United States, including local telephone calls." The request was only for three months, but intelligence committee chair Senator Feinstein suggested that such a request could be frequently renewed if approved by the court.

Every member of the United States Congress can ask for briefings on national security legislation before voting on them, but they often don't, relying instead on the expertise and opinions of colleagues who serve on the relevant committees.

"Non-committee members really are not informed," says Greg Theilmann, a former Senate intelligence committee staffer now with the Arms Control Association. "It's only the members of the intelligence committees of Congress that get the briefings and have the staff that can develop sufficient expertise to understand and help them ask the probing questions." Judiciary committee staffers also receive briefings from the intelligence community but don't always get the same level of access that the intelligence committee does.

The cliche is that Washington is riven by partisan rancor, but when national security powers are up for renewal, legislators find a way to clasp hands and work together. Since being passed in 2001 the PATRIOT Act, under which the request to Verizon for Americans' communications records was made, has been reauthorized by large margins, no matter which party held Congress or who occupied the White House.

During the debate over legislation related to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, Congress twice voted down attempts to compel public disclosure of NSA surveillance and of legal opinions reached by the secret court that approves requests for data like the one made to Verizon. Defenders of the Obama administration can point out that unlike the secret warrantless wiretapping program discovered under the Bush administration, these surveillance powers have been consistently approved by Congress. Feinstein's office provided msnbc with two letters showing that classified reports on the section of the PATRIOT Act cited in the Verizon order were made available to all members of the Senate in 2010 and 2011.

But again: just because legislators voted to approve sweeping surveillance powers doesn't mean that they understood them. In the Senate, intelligence committee and judiciary committee members have at least one staffer designated to them by the committee. In the House, even intelligence committee members do not have staff designated to them with the necessary security clearance to discuss such matters—they have to rely on information given to them by staffers on the committee. Individual members of Congress who are not on those committees can go to a secure room called a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (or "skiff") to receive briefings from congressional staff with the relevant expertise, or they can read confidential reports describing intelligence-gathering programs-- but not many do, either because they are uninterested or because they are busy with other matters.

Even if those interested legislators do get briefings, many can't talk to their staff about them because their staffers don't have the necessary security clearance. So legislators have to rely on what the committee staff—who in turn have to trust that the intelligence community or the administration is being up front—tell them. Particularly when it comes to digital surveillance, the briefings can be highly technical and sometimes fly over the heads of legislators who were born decades before computers were in regular use. These complex issues can take a long time to master, while there are an infinite number of other important matters vying for a legislator's attention at any given time.

"Reliance on staff in matters of national security, outside of the members who really focus on national security, is absolute," says Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center, a former counsel to former Democratic Senator Russ Feingold of Wisconsin. "If you don't have a staffer that can help you with this, you're out of the game."

Two senators who have been most vocal in criticizing the Obama administration's surveillance policies are Democrats Ron Wyden of Oregon and Mark Udall of Colorado. In 2011, Wyden and Udall sent a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder warning that Americans would be "stunned" to learn how broadly the Obama administration and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court was interpreting the PATRIOT Act.

Following Feinstein and Chambliss' press conference on Thursday, Wyden released a statement saying he had long been concerned about the surveillance policies they defended. "When law-abiding Americans call their friends, who they call, when they call, and where they call from is private information," Wyden said. "Collecting this data about every single phone call that every American makes every day would be a massive invasion of Americans’ privacy."

"Those two senators have been able to be so organized and vocal because they have dedicated staff who can get into this arcane area of the law and really understand what's going on," says Michelle Richardson, an attorney with the ACLU. Wyden's statement Thursday also hinted at how circumscribed the public debate truly is, with Wyden stating that he was "barred by Senate rules" from "commenting on some of the details at this time."

Some legislators who aren't privy to the kind of detail intelligence committee members get do take the time to learn about how the government is conducting national security policy. Oregon Democratic Senator Jeff Merkley, who is not on the intelligence or judiciary committees, tried last year to change the law so that the secret FISA court opinions interpreting legislation like the PATRIOT Act would be made public. Merkley called the revelations "an outrageous breach of Americans' privacy" in a statement Thursday.

"Knowing about this stuff, and having the opportunity to know about it are obviously two different things," says a former Obama administration official. "If you voted for it, and you express surprise now, you're either being disingenuous or you didn't do your job."

Despite voting on these laws, Theilmann says that past experience suggests that legislators don't necessarily know a lot about them. He pointed to the fact that only a handful of legislators who voted for the war in Iraq in 2003 actually took the time to go read the classified intelligence estimate on Iraq held in a secure room in the Capitol.

"That was an issue of war and peace," says Theilmann points out. "That gives an idea of how frequently members go to a highly classified space to inform themselves."