EL DORADO, Ark.—Spend a few days in Arkansas and you’re almost sure to hear the unofficial state slogan: Thank God for Mississippi.

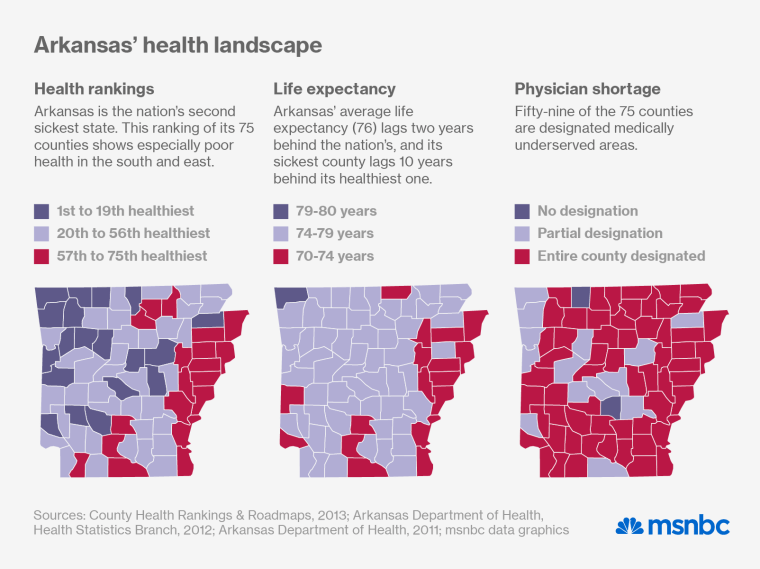

Arkansas is the second sickest state in the nation (Mississippi, its eastern neighbor, takes the prize), and it lags far behind national averages on most measures of human development, from education and income to life expectancy. A fifth of its 2.9 million residents live in poverty, a similar proportion lack health insurance, and even those with coverage often get low-quality care. In 2011, a statewide survey found that only 28% of diabetics and 30% of people with high blood pressure had their conditions under control. All this despite a decade of devastating, unsustainable increases in health-care spending.

Yet despite these challenges, and partly because of them, Arkansas is now pioneering some of the nation’s most creative, ambitious efforts to transform health care. Its groundbreaking approach to Medicaid expansion made national headlines this month, when it survived a close reauthorization vote in the legislature. But the Medicaid experiment is just part of Arkansas’ broader effort to reinvent health care. The other challenge—more audacious, more complicated and just as critical—is to build a payment system that rewards doctors and hospitals for the value, rather than the volume, of services they provide.

The state’s Democratic governor, Mike Beebe, had no particular interest in health care when he assumed office in 2007; he wanted to improve education and expand the state’s economy. But when the recession struck in 2008, he realized he had to confront health care—if only for economic reasons. The cost of private health insurance had nearly doubled in less than a decade, and the recession made it all the less affordable. The growing ranks of uninsured workers were handicapping employers through illness and absenteeism and ravaging the state treasury through Medicaid claims and unpaid medical bills.

“The Governor realized he had to fix health care in order to get anything else done,” says Arkansas Surgeon General Joe Thompson. “And that meant fixing the way we pay for it.”

The rural road to cost control

Consensus is rare in health care politics, but virtually no one believes that America’s fee-for-service payment system is sustainable. It rewards providers for administering more treatment, not for keeping people healthy enough to avoid it. So costs rise but outcomes don’t improve. Per-capita health care spending in the U.S. now tops $8,200 a year—more than twice what France, Belgium or Sweden spends—yet we trail the rest of the developed world on virtually every measure of health and well-being.

To break the cycle of rising costs and diminishing returns, the federal government is seeding new payment schemes through the Affordable Care Act. In the most popular model, a large health system or medical practice forms an “accountable care organization,” or ACO, which accepts a fixed fee, or “bundled payment,” to provide a certain type of care. Instead of racking up invoices for every service a patient receives, the ACO works to achieve the best possible outcome in the most efficient way. If the practice can achieve good outcomes for less than the bundled payment, it gets to keep a share of the savings.

The ACO model can work well in urban areas that have large, integrated, full-service medical practices, but health care is still a cottage industry in more rural states like Arkansas. Solo practitioners are still common here. Most group practices have fewer than six doctors, and they’re often many miles apart. Fifty-nine of the state’s 75 counties are designated medically underserved areas, and it’s easy to see why as you drive Route 167 through the center of the state, from Little Rock down to El Dorado, near the Louisiana border. The scattered towns and trailer parks are hardly big enough to support a KFC, let alone an ACO.

In light of that reality, the state’s health officials have devised an alternative model that meets the providers where they live. Under the state’s new payment system, doctors and hospitals will continue to receive piecemeal payments rather than global ones, but they’ll have new incentives—and new opportunities—to trim waste and coordinate their services. “Physicians agreed that 20 to 30% of the money in the system was being wasted,” says Thompson, the new model’s leading advocate. “We realized we could keep paying claims the old way if providers had incentives cut that waste.”

Unlike the ACO model, which limits spending by limiting payments up-front, the Arkansas system uses after-the-fact analysis to reward efficient care. At the end of each year, participating payers will use a common set of benchmarks to analyze billings. If the analysis shows that a practice has exceeded the “acceptable” cost threshold for a certain type of care, the practice will have to repay a portion of the excess. But if the billings come in below a “commendable” level for that same care, the practice will receive a check for share of the savings. The waste and excess that once drove profits will now reduce earnings. The efficiencies that used to pinch providers’ billings will now help them prosper.

A moon shot instead of a pilot project

That’s the theory, anyway. ACOs can be designed and tested individually, in low-risk pilot projects, but Arkansas doesn’t have that luxury. In order to work at all, its model needs a wide array of insurers and providers to rethink their business models. Willing providers must work as teams rather than soloists and rigorously track their own performance, both individually and at the practice level. And participating insurers must adopt a standardized, statewide payment system designed to track quality and efficiency rather than second-guess specific medical decisions. “Our whole system was in dire jeopardy,” says Thompson. We didn’t have the luxury of running pilot projects. It was all or nothing.”

It’s far too soon to call the effort a success, but it’s taking off fast and meeting surprisingly little resistance. The state’s Medicaid program and its largest private insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arkansas, are both on board, as are its biggest self-insured employers. And clinical sites serving nearly a half-million Arkansans have tapped into the statewide database that will standardize billing and reimbursement. Stakeholder groups have agreed on cost and quality benchmarks for a half-dozen “episodes,” including upper respiratory infections, child birth, total joint replacement and congestive heart failure. Participating medical practices could see their first “shared savings” payments as early as next month. In a December progress report, Thompson noted that the quality of care was already improving in some of those areas: less misuse of antibiotics for viral infections, more prenatal screenings, and fewer cesarean births.

By 2017, the state expects to have payment models in place for 75 to 100 clinical episodes, casting the new net over 50% to 70% of the state’s medical spending. By that time, it also expects most Arkansans to get their primary health care through patient-centered medical homes, using similar incentives to improve outcomes and reduce waste

A home instead of an escalator

The medical home isn’t an Arkansas invention; it’s a national strategy, enshrined in the Affordable Care Act, to revive the nation’s failed primary care system. Instead of a brief annual encounter with an internist, a patient with a medical home gets continual support from a team of health workers, many of them non-MDs, who offer the routine services the person needs to stay well. And the doctor doesn’t perform as a soloist. Each one leads a team while tracking its performance on basic measures of quality, such as vaccination rates for seniors, colonoscopy rates for people in their 50s, and blood-pressure control among people with hypertension.

Under Arkansas’ payment reform initiative, medical homes will bill insurers for services rather than taking a flat annual payment for each patient. But like the specialized practices that handle “episodes,” they’ll profit by reducing waste rather than creating it. A traditional primary care practice can’t even track the health of its patients as a group. But a state-of-the-art medical home knows how many of its patients have particular needs—and how well its providers are meeting them. If a year-end analysis shows that a group’s routine services have helped prevent costly medical crises (e.g., pneumonia, colon cancer and stroke), the practice will get a share of the savings.

Building a medical home requires staff, skills and technology that few small practices can afford. But as one of seven states participating in Medicare’s Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, Arkansas has already helped 69 of them make the transition. One early adapter is SAMA Health Care, a longstanding group practice based in El Dorado (population 18,491), the largest metropolis between Little Rock and Shreveport. Until recently, SAMA’s four docs worked independently, rotating their shifts so that everyone got regular days off, and the nurse practitioners filled gaps.

They all saw the futility of encounter-based medicine (treating illness rather than preventing it), but they lacked the resources to build practice devoted to health. Everything changed when they heard that the Medicare initiative was funding innovative proposals to turn traditional practices into medical homes. After sitting through a briefing, Pete Atkinson, SAMA’s sharp young administrator, flipped over a pizza box, grabbed s marker, and drew a circle around four smaller ones—each representing a team composed of a doctor, a nurse practitioner, a care coordinator and three RNs.

With some back-of-the-box calculations, the SAMA docs realized they could transform their facility and their practice for $500,000, and guessed that they could sustain it by reaping the new rewards for efficiency. The Medicare grant provided $400,000 and they raised another $100,000 on their own. “We had wanted to do this for years,” says Dr. Gary Bevill, one of the group’s founding partners. “Once we got the resources, we jumped out of the gate.”

Twenty months later, SAMA is a picture of what primary care could and should be. The clinic’s four teams, sporting color-coded scrubs, work as units to ensure that each of their patients gets enough care, support and follow-up to stay well and avoid hospitalization. The group’s technology guru, Nancy New, documents their performance in quarterly reports that quickly highlight lapses or weaknesses. Sitting at her screen, she tosses off graphs comparing the status of the four teams’ patients and checking the clinic’s overall performance against state and national averages. At a glance, we see that 40% of SAMA’s diabetic patients got potentially limb-saving foot exams last year—compared to 10% nationally—and that the clinic’s on-site services prevented 880 emergency room visits, saving the system a quick $2.6 million.

Matt Salo, director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors, ranks Arkansas’ health care innovators among the smartest in the country—a happy coincidence when you consider that they’re facing the country’s worst health care challenges. If they succeed at transforming the payment system, other states may soon croon Thank God for Arkansas—and mean it.