GOT QUESTIONS ABOUT WENDY DAVIS, GREG ABBOTT, AND THE TEXAS GOVERNOR'S RACE? ASK OUR NATIONAL REPORTER ZACHARY ROTH HERE.

McKINNEY, Texas -- When Greg Abbott announced his campaign for governor of Texas last summer, he talked about keeping taxes low, securing the border, and improving education. But the date that Abbott chose for the kickoff—July 14—was as significant as anything he said. On that day in 1984, Abbott was out jogging with a friend in Houston when a falling oak tree hit him in the back, crushing his spine and paralyzing him for life at 26.

Abbott’s disability is surprisingly central to his campaign—and he uses it mostly as evidence of the kind of “toughness” conservatives revere.

At a recent campaign event in McKinney, outside Dallas, Abbott, 56, recalled how doctors pieced together fragments of his shattered vertebra and implanted metal rods in his back. Countless politicians, he said, promise that if elected they’ll have a spine of steel. “Well, I really do have a steel spine that I use to fight for you and your families every single day,” he shouted, as the crowd, heavy on retirees and local Republican activists, roared its support.

A staunch conservative who is currently Texas’s attorney general, Abbott has the record to back that boast up. He likes to point out that he’s filed 30 lawsuits against “Barack Obama”—never President Obama—and his administration.

“I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home,” Abbott has said.

Abbott has sued over Obamacare and over administration efforts to fight global warming, and he’s sued Attorney General Eric Holder to let Texas implement its strict voter ID law—a resume item that drew raucous cheers among the nearly all-white crowd in McKinney.

At the same time, a kind of sober, no-frills competence is central to Abbott’s appeal. “I like him, I trust him, and when I go to bed at night, I can feel safe with him in the governor's mansion,” Eugene Lund, a retiree from nearby Sherman, told msnbc after Abbott’s campaign appearance here.

Next year, Abbott is likely to have an even more powerful perch from which to wage his campaign against Obama. He easily won the Republican gubernatorial primary Tuesday night, and he’s the overwhelming favorite in the general election. His Democratic opponent, state Sen. Wendy Davis, is generating excitement and campaign cash after her 11-hour filibuster over strict abortion restrictions made her a national figure. But no Democrat has won statewide in Texas in two decades.

If Abbott wins in November, expect America’s second-largest state to continue on the hard-right course it’s pursued under current Gov. Rick Perry—only more so.

But the race could also have implications beyond the Lone Star State. Abbott’s election would make him the most important Republican executive in the country. The last two Texas governors, Perry and George W. Bush, have gone on to run for president, and already there are whispers that Abbott could have a national future.

Democrats have their eye on Texas, too. Davis’s high-profile candidacy, combined with the state’s growing Latino population, has helped stoke a new optimism among the state’s Democrats—with backing from some high-level Obama campaign veterans—determined to turn Texas blue. That won’t happen overnight, but if it ever does, it would represent a tectonic shift in the national political map, eliminating the GOP’s largest, richest and most culturally prominent stronghold, and giving Democrats a perhaps-decisive upper-hand in national elections.

As the next de facto leader of the Texas GOP, likely for many years to come, it’s Abbott—not just a conservative crusader but a disciplined, pragmatic campaigner and a tough-as-nails competitor whose focus and determination can’t be doubted—who’ll be standing in the way.

“You never look back”

At campaign stops, Abbott likes to talk about his plan to ease traffic congestion by building more roads—without raising taxes, of course. He says he wants to run a campaign ad on the issue, featuring a wide-angle shot showing hundreds of cars stuck on the freeway. As he described the ad at the McKinney event, Abbott deftly maneuvered himself to one side of the stage. “We’ll pan in closer—and then we'll see a guy in a wheelchair rolling right past them,” he said as he wheeled himself joyfully from left to right in front of the crowd.

Abbott’s next line—“vote for me and I will get traffic moving in the state of Texas”—was drowned out by the crowd’s laughter and applause. But that was OK, because he wasn’t really talking about traffic anymore. He was instead telling people that it’s alright to relax a little, that they don’t need to treat him like a victim or a delicate object. It’s an enormously charming and self-deprecating performance, and at three separate campaign events in different cities, the laughter it produced had a quality of gratitude and relief that made it clear he’d won the room over about as completely as a politician can.

Abbott has also put his disability to a stranger use. Asked by a reporter whether he regretted campaigning with Ted Nugent, the controversial right-wing singer who recently called Obama a “sub-human mongrel” and has admitted to sex with underage girls, Abbott said no.

“When I had the tree crash down on my back, it changed my life forever,” he answered, with an immediacy that made clear the line was carefully prepared. “A lot of people ask me, do you have any regrets going out jogging? What would you have done differently? Could you have run faster or slower? Could you have done anything to avoid the accident? I learned at that crucial time in my life, you never look back."

In some ways, he hasn’t. The accident nearly killed Abbott and led him to apply a new level of discipline in his professional life. He went to work at a law firm while still wearing a body jacket and learning how to move in it, Abbott told the Texas Monthly for a profile last October. He prepared intensely for cases, then, after growing frustrated with judges who were less prepared than he was, ran for the bench himself and won. From there, he was appointed by then-Gov. Bush to the state Supreme Court, twice winning re-election, before being elected attorney general in 2002.

Over the last year, Abbott has shrewdly outmaneuvered several potential GOP rivals for the governor’s mansion, leaving himself with a few no-name opponents whom he easily dispatched Tuesday, winning 91% of the vote. Across more than two decades in politics, Abbott has never lost an election.

Related: Have a question for the reporter of this piece? Ask him here.

When Ted Cruz ran for the Senate in Texas in 2012, he was able to outflank a far better-funded GOP primary rival by highlighting the cases he brought against the Obama administration, as solicitor general. What Cruz didn’t often say was that many of those cases were driven by his boss, the Attorney General Greg Abbott.

It’s fair to put Abbott near the very top of the list of figures who have worked to set back voting rights recently. In the voter ID case, his office argued that the ID law is legal because it discriminates against Democrats, not blacks and Hispanics. If accepted, that claim would make it all but impossible to use the Voting Rights Act to stop any but the most blatant forms of racial discrimination in voting, dealing another major blow to the law after it was badly weakened last year by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (Abbott submitted an amicus brief in support of Shelby County in that case).

Abbott isn’t just crafting far-reaching legal arguments for voter ID, he’s actively running on it. On the campaign trail, he talks about the need to crack down on voter fraud, citing an ongoing FBI probe into alleged illegal voting in south Texas that has already netted several arrests. He doesn’t mention that an ID requirement would have done nothing to stop the scheme.

In some ways Abbott’s profile recalls that of another southern attorney general who recently ran for governor after waging a series of high-stakes court battles with the Obama administration: Virginia’s Ken Cuccinelli. But there’s an important difference.

Cuccinelli, who lost his bid for a promotion last year to Democrat Terry McAuliffe, is a movement conservative—he recently opened a law firm dedicated to protecting Second Amendment rights—whose true-believer zeal sometimes got in the way of his political ambitions.

No one doubts Abbott’s conservative convictions. But his steady rise, his unquestioned focus and discipline, and his success in positioning himself almost as the inevitable next governor suggest a politician who’s driven as much by the desire to gain and wield power as by a wish to change the world. In short, Wendy Davis may not have gotten as lucky in her opponent as McAuliffe did.

Pulling up the ladder

A different candidate might find something else, too, in living with a disability—a way to demonstrate, and perhaps even feel, empathy with those who are struggling. Doing so might help Abbott distance himself a bit from his party, which is seen even by some Texans as too severe and unforgiving. It might also help counter Davis, whose inspiring life story—though a point of contention in the press—is central to her appeal.

The line in the stump speech almost writes itself: “Friends, I may be a Texas lawman, and a conservative, too. But I’ve been through my share of challenges, and I know firsthand that life doesn’t always go according to plan,” he might say.

But Abbott appears never once to have said anything like this publicly. In fact, there’s little to suggest that’s part of how he thinks about himself.

The tree that caused Abbott’s injury fell from the yard of a wealthy Houston divorce lawyer, and Abbott sued, winning a payout that currently totals around $5.8 million, and will continue for the rest of his life. But since the 1990s, he’s supported various conservative efforts to make it harder to sue, including a controversial 2003 Texas law that capped non-economic damages in medical malpractice cases at $250,000.

Abbott told the Texas Tribune last year that someone in his situation today “would have access to the very same remedies I had access to,” and experts haven’t universally contradicted that. What’s clear, though, is that he didn’t emerge from the experience of being paralyzed committed to ensuring that other accident victims have the same recourse he did.

Abbott’s approach to disability rights tells a similar story. He’s said he supports the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and has benefited from it personally. But as attorney general, he has argued that it’s unconstitutional to force states to comply with the ADA, another far-reaching legal claim.

Abbott marshaled that argument when he fought in a series of cases to prevent disabled Texans from using the ADA to sue the state. In one case, Abbott opposed two deaf defendants who wanted a qualified sign-language interpreter in their courtroom. In another, he went up against a blind professor who asked for reflective tape on the stairs to her office.

“A big point of the ADA was to ensure that states themselves would not discriminate against—and would provide reasonable accommodations to—people with disabilities,” Sam Bagenstos, a leading disability-rights lawyer who has argued several major ADA cases before the Supreme Court, said via email. “Had Abbott's office prevailed in that argument, that would have cut a major hole in the statute.”

Turning Abbott into Akin

When Davis launched her campaign back in October, there was a sense that—though Abbott was the clear favorite—her inspiring personal story backed by a strong grassroots push by Democrats might be enough to at least upend the conventional GOP-friendly dynamics of Texas politics.

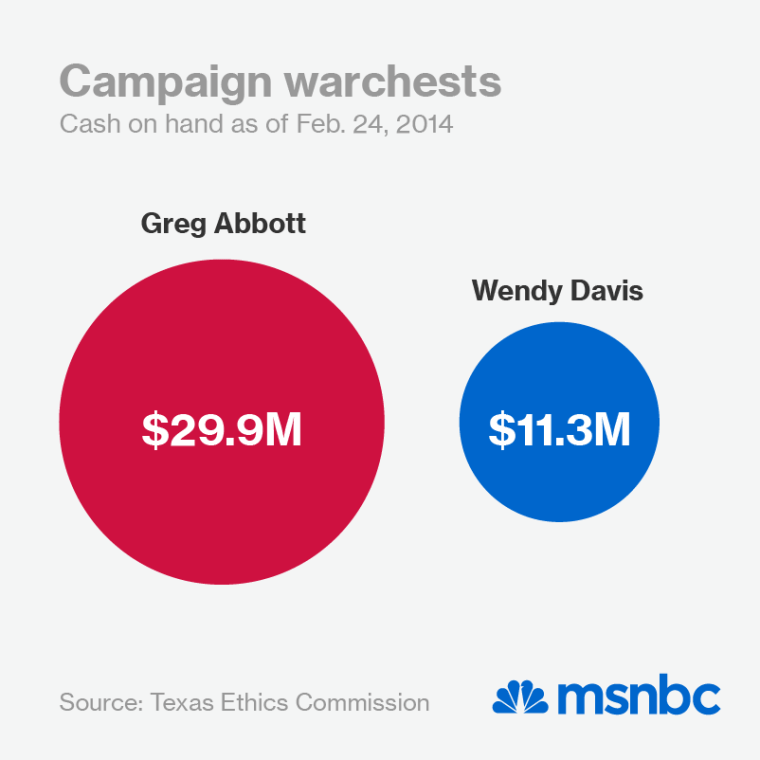

These days, things have settled back into a more familiar pattern. A Texas Tribune poll conducted in mid-February showed Abbott up by 11 points—not much less than the 15 by which Mitt Romney defeated Obama in Texas in 2012. Despite Davis’s impressive fundraising, Abbott’s $30 million in cash on hand is nearly triple what she has.

Close observers of Texas politics say Abbott has benefited from the Davis camp’s failure to define him negatively since the fall—a failure attributable in part to Team Davis's need to raise money and stand up a campaign structure.

“It's not a slam-dunk that if the Davis campaign had mobilized earlier that they'd now somehow be ahead," said James Henson, who runs the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. "But I think it would have made more of a campaign of it.”

Abbott’s embrace of Nugent—who Abbott called a “fighter for freedom”—may have given Davis’s team their first real opening on that front. The Davis campaign’s countless press release attacks over the issue have focused like a laser not on Nugent’s racial anti-Obama comments, but on his predatory sexual behavior. The goal is to raise doubts about Abbott with women voters—especially the suburban women who the Davis campaign sees as the race's key swing demographic.

Henson said the Nugent brouhaha may be starting to drag Abbott down a bit. But he thinks that, unless it merges with another story to ignite a broader gender politics controversy in the race, it likely won’t have much lasting effect.

“While this has been disruptive on the surface, I don't think it changes the fundamentals,” Henson said.

The Davis campaign will keep trying to ignite that gender controversy—and they’ve got no shortage of material to work with. But Abbott might not be easy to portray as the second coming of Todd Akin, the 2012 Missouri GOP Senate hopeful whose comments about "legitimate rape" torpedoed his candidacy.

It’s not just that Abbott’s likely too smart and deliberate a campaigner to fall prey to an Akin-like gaffe on the trail—though that’s important. It’s also because of something less concrete: One reason Abbott may have chosen not to explicitly use his disability to demonstrate empathy is that he doesn’t have to. The simple sight of him in his wheelchair—matchstick-thin legs dangling in front of him as he maneuvers himself around—is enough to set him apart from the parade of conservative Republican white men who talk about helping the job creators and seem never to have suffered a day in their lives.

Put simpler: It’s hard to turn a guy in a wheelchair into a villain—no matter his record.

Reporter Zachary Roth is taking reader questions about his reporting in Texas and the Abbott/Davis race. Leave your question for him in the comments under msnbc Community.