Home care workers bathe your mother and change your father’s bandages. We cook for your grandmother and help your grandfather use the toilet. We help your brother or sister with their physical therapy. But despite doing the hard work that enables older Americans and people with disabilities to live with dignity and independence in their own homes, few people understand that home care workers can barely take care of their families.

But I’m determined that will change. And I’m not alone.

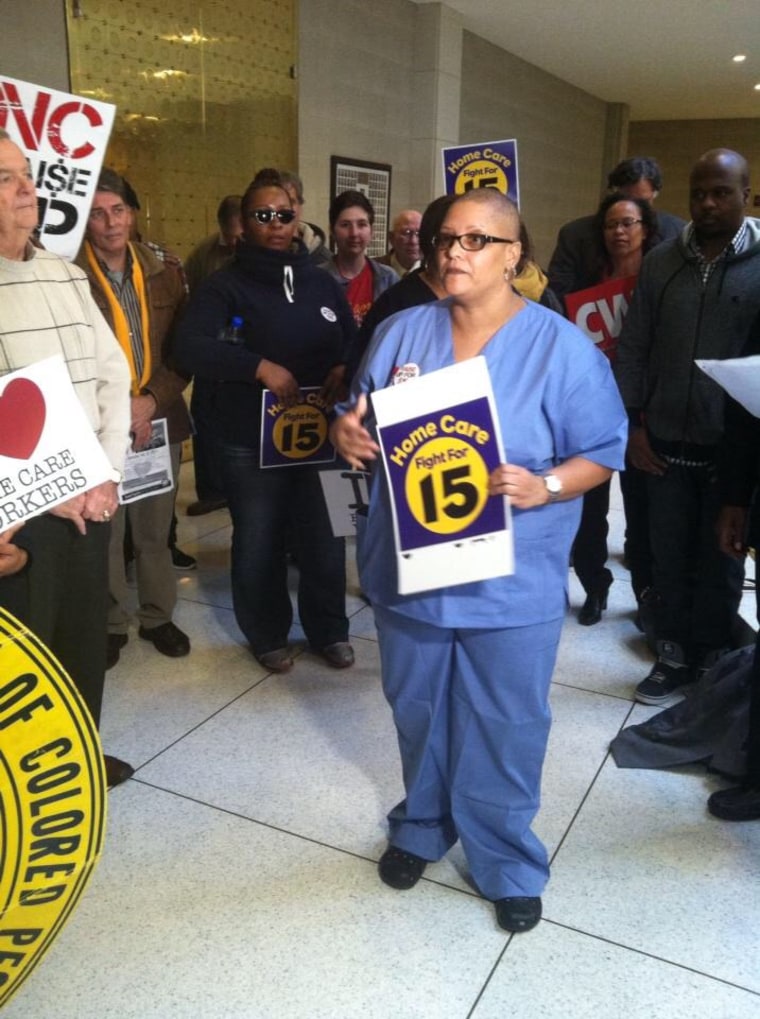

This week I’ll join home care workers in Raleigh and thousands more in 20 cities across the country as we gain momentum in our growing fight for $15 and a union.

What started in September, with home care workers in a handful of cities joining together with fast-food workers to call for higher pay and better rights, has now spread from coast to coast. And beginning this week, as we hold town hall meetings in every corner of the country with members of the clergy, community leaders and government officials, including Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez, we are saying loud and clear that our call for $15 and a union needs to be heard.

I work for three different home care agencies and the last raise I received was a year ago, to $10 an hour, from $9.75, after five years of service. Additionally, none of the three agencies I work for provide medical benefits, paid vacation or sick leave to workers. If I have to miss work because I’m sick or if I have an emergency, I don’t get paid.

RELATED: Home health workers push for higher wages

Sadly, I’m not alone. The median salary for America’s 2 million home care workers is $13,000. It’s almost impossible to support myself on such low pay. And the burden of the industry’s low pay falls disproportionately on women of color like me. Nationally, the home care workforce is 91% female and 56% non-white.

I take care of clients who have a variety of backgrounds. In a normal day I bathe them, prepare their meals, drive them to appointments and help with their physical therapy. Over the years I’ve become their trusted caregiver and the front line of their healthcare team. It’s because of the connection I have with my clients that I love my job. But the wages I am paid are so low that I have to work 90 to 120 hours a week just to scrape by. It’s not uncommon for me to work 72 hours straight, taking 20 and 30-minute naps in the car before my next client.

"The wages I am paid are so low that I have to work 90 to 120 hours a week just to scrape by."'

There are countless days that I’ve gotten an hour of sleep after coming home from a 12-hour shift, only to receive a call asking me to drive across town to a new three-hour assignment. It’s hard to do that day after day on these wages. And after a while it’s hard to deliver high quality care to clients on only a few hours of sleep spread across two or three days.

A pay raise to $15 an hour would allow me to work more livable hours and help me to save for my retirement. I’m 50 years old and my agencies do not provide retirement benefits. If I want to ensure my stability for the future, I need $15 an hour.

Raising pay in the home care industry won’t just help workers like me. It is also a critical priority for aging Americans and their families across the country. As the baby boom generation ages over the next 10 years, the number of people who need home care to stay out of nursing homes is going to double. By 2022, 1 million more home care workers will be needed to care for America’s seniors and people with disabilities and more home care jobs will be created than any other occupation in America.

Where will the home care workers we need to meet that challenge come from? Who will want to enter this profession for a poverty wage and little or no paid time off? Shouldn’t these jobs be good jobs that pay workers enough to support ourselves, our families and our communities? I think so, which is why I’m joining thousands of home care workers in town halls across the country this week to add my voice to the call for $15, a union and a better future for my family and those families who depend on workers like me to care for their loved ones.

Kimberly Thomas has been a home care worker in North Carolina for six years. She is one of many workers from N.C. who are joining thousands of home care workers across the country in town halls as they call for $15 and a union.