Researchers said Tuesday they had found an even easier way to "edit" DNA using a controversial new technique and said they'd share it immediately.

But that announcement only added real-time urgency to a summit in Washington called to address the fast-moving field of genetic alteration. At the meeting, some scientists and advocates have been calling for researchers to take a voluntary breather from the research, while others say it would not only be unethical to do so, but impossible.

"We could be on the cusp of a new era in human history," Dr. David Baltimore of the California Institute of Technology said in opening the conference, sponsored by the national science academies of the U.S., China and Britain.

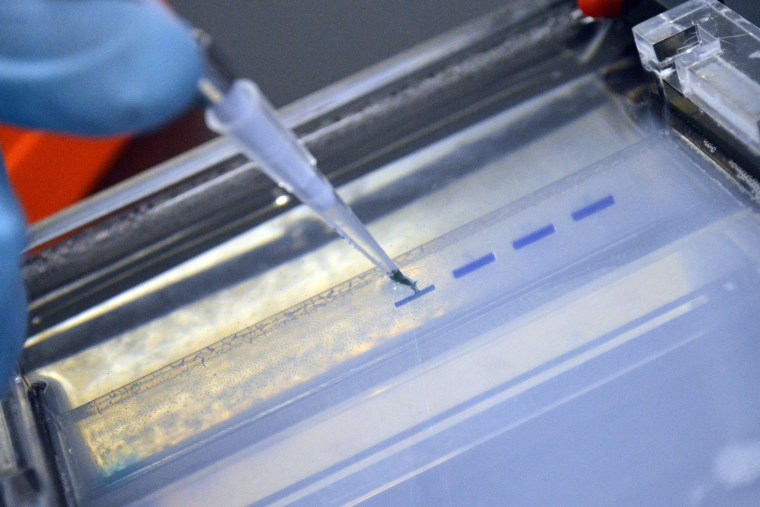

Gene editing is a simpler and more precise way to do what scientists have been doing for decades now: changing DNA to improve crops, customize farm animals and cure disease. It harnesses the abilities of, for instance, bacteria and viruses to precisely cut and paste stretches of genetic material in a cell's nucleus.

The new methods are not perfect but they are cheaper and easier to use than old-fashioned techniques that often relied on viruses to carry the desired genetic changes.

RELATED: Why Congress is having a food fight over GMO labeling

"It is very, very inexpensive," Robin Lovell-Badge, a geneticist at Britain's Francis Crick Institute, told reporters. He said it's available to students and even hypothetical scientists working in a garage.

Feng Zhang and colleagues at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT made improvements to one of the most popular new methods, called CRISPR (short for Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats). Their new approach produced fewer mistakes, called "off-target effects", when they tested it in human kidney cells in a lab dish.

"Many of the safety concerns are related to off-target effects," Zhang said in a statement. But he said the discovery, reported in the journal Science, isn't the last word on safety. "The field is advancing at a rapid pace, and there is still a lot to learn before we can consider applying this technology for clinical use," he said.

The main worry is that the technology could so easily be used to change the human germline - permanently altering DNA that's passed from parent to child. While that might seem like a miraculous way to eradicate disease with simple genetic causes, such as sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis, experts point out that no one knows enough about genetics yet to be sure there would not be unintended consequences.

For instance, gene therapy can cure rare inherited immune system syndromes, but it sometimes inadvertently also causes leukemia in babies.

The White House and National Institutes of Health director Dr. Francis Collins have both asked for a voluntary moratorium on so-called germline editing until scientists can learn more.

But several experts speaking at the conference pointed out it would be almost impossible to enforce such a pause in research. European countries have a legal ban on germline modification, but Chinese scientists are moving ahead.

The U.S. is a mixed bag - federal funds may not be used to alter embryos at all, but private companies or researchers using private funds may do as they wish.

RELATED: Sorry, Gwyneth Paltrow, GMO labels won’t tell you what you want to know

There are not clear battle lines. Some scientists support moratoriums or even bans on certain work, and some ethicists strongly denounced any idea of stopping the research.

"Just as justice delayed is justice denied, so therapy delayed is therapy denied," John Harris, a bioethicist and professor at Britain's University of Manchester, told the conference.

"Before we make permanent changes to the human gene pool, we should exercise considerable caution," the Broad Institute's Dr. Eric Lander said.

Harris dismissed the common argument that anyone who edits the germline of a child is making a decision for future generations who get no say in the matter. "All parents decide for their present and future children," he said.

Others raised the specter of eugenics — trying to create a more "perfect" society — and abuses such as the case of researchers who deliberately let African-Americans develop syphilis in Tuskeegee, Alabama for 40 years, until the experiment was stopped in 1972.

Most of the scientists actually working in the field say the debate has exaggerated just what's possible and what's not.

Lovell-Badge says while people may be tempted to try to design smarter, better babies, it's not a straightforward task.

"Of course we don't know enough to be able to do a lot of this stuff," Lovell-Badge said. "Certainly for intelligence we are a long way off from understanding anything like enough about the genes involved to be able to alter anyone with this technology," he said.

It's easy to make animals that glow green under fluorescent light, he noted. It might be "very useful for discos but not much else," he joked.

Even most disease genes have a modest effect and it usually takes a combination of several "bad" genes, plus changes in the environment such as infections or diet, to result in disease, experts told the conference.

And while the technology might be cheap and widely available, it's one thing to genetically alter yeast, Lovell-Badge said. "If you are going to do it on human embryos, that is going to be very difficult," he said.

So far, no one's publicly genetically altered a human embryo that survived and the only group that's admitted to it, a team of Chinese scientists, said the experiment failed.

This article first appeared on NBCNews.com.