There’s been no shortage of ink spilled over the practical impact of last week’s bombshell Supreme Court campaign-finance decision, McCutcheon v. FEC. Depending who you talk to, it portends either the triumph of free speech or the road to oligarchy.

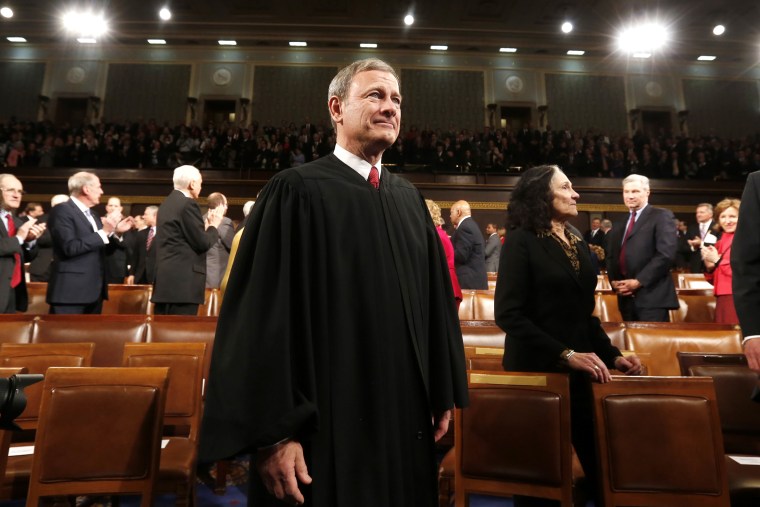

But much less has been written about a notable feature of the decision itself: Parts of Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion appear to contradict each other.

And that is no anomaly. In several of his most politically-charged decisions -- on health care, voting rights, campaign finance -- Roberts has embraced what are arguably contradictions, abandoned precedent without explanation, or both.

The question is: why? Roberts is a brilliant man, so these are no mistakes in legal reasoning. Instead, they make it easier for his critics to advance a narrative about the chief justice that first began to circulate after his Obamacare decision: that he’s willing to make unorthodox legal moves, or refrain from following his own reasoning to its endpoint, to shift the law in the direction he’d prefer.

Roberts’ campaign-finance opinion provides the latest fuel for that fire.

In the Supreme Court’s first big campaign-finance case a generation ago, Buckley v. Valeo, the court concluded that Congress may cap how much money an individual can give a candidate because that doesn’t infringe speech rights. Such a limitation, it wrote, “involves little direct restraint on his political communication” because it still “permits the symbolic expression of support evidenced by a contribution.”

That logic underpins the contribution limits that have been part of federal law ever since. And in last week’s opinion in McCutcheon, Roberts professed to reaffirm it: He quoted the sentence above from Buckley and emphasized again and again that the court was not striking down individual contribution caps.

And yet, in the same breath, Roberts rejected the exact same proposition. The Obama administration had defended the aggregate caps in federal campaign-finance law -- caps on how much an individual can give to all candidates combined -- by arguing that even with the caps “an individual can engage in the 'symbolic act of contributing' to as many entities as he wishes."

That is almost a direct quote from the Buckley decision, and Roberts shot it down. “It is no answer to say that the individual can simply contribute less money to more people," he wrote, because limiting how much a person can donate to a candidate unconstitutionally “impose[s] a special burden on broader participation in the democratic process."

As Justice Clarence Thomas pointed out in a concurring opinion, Roberts’ opinion was at war with itself. Thomas expressed palpable frustration that Roberts hadn’t followed his own logic and overruled Buckley altogether. “What the [Roberts opinion] does not recognize,” he wrote, is that its logic “also defeats the reasoning from Buckley on which [Roberts] purports to rely.”

If that was déjà vu for court watchers, it’s because several of Roberts’ past opinions have drawn fire on similar grounds.

In the Obamacare decision, for example, Roberts wrote a long opinion making dramatic new law -- concluding, for the first time ever, that Congress can’t regulate “inactivity” -- even though that discussion turned out to be totally unnecessary to the case’s outcome.

That is a basic no-no for federal judges, and in her opinion Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg expressed her exasperation. “Why,” she asked, “should the Chief Justice strive so mightily to hem in Congress’ capacity to meet the new problems arising constantly in our ever-developing modern economy” in a case where there was no need to discuss it? She concluded: “I find no satisfying response to that question in his opinion.”

A year later, Roberts wrote the court’s opinion striking down a key part of the Voting Rights Act. He based his conclusion in part on the principle of “equal sovereignty” -- the idea that all states are equal and must be treated as such. That principle, Roberts wrote, was offended by a law that forced only a few states to submit their voting laws to federal review.

In dissent, Ginsburg pointed out that Roberts’ use of the equal-sovereignty principle was wrong, and obviously so: The court had held in an earlier, binding case that the principle “applies only to the terms upon which States are admitted to the Union, and not to the remedies for local evils which have subsequently appeared.” Equal sovereignty, in other words, had nothing to do with anything. Roberts, she wrote, “veers away from controlling precedent . . . without even acknowledging that [he] is doing so.”

Each of these opinions is very different, and the flaws the other justices claimed to identify in each opinion are different in kind too. But taken together, it is fair to say that they leave Roberts open to the claim that he moves the law in the direction he thinks best, at the speed he thinks best, without letting the usual limitations on a judge’s freedom to maneuver stand in the way. Time will tell what impact that narrative could have on his legacy, and that of the high court.

Dominic Perella is a partner in the law firm of Hogan Lovells, where he specializes in Supreme Court and appellate litigation.