The Iraqi people can be certain of this. The United States is committed to helping them build a better future. We will bring Iraq food and medicine and supplies, and most importantly, freedom.

—President George W. Bush, addressing religious broadcasters in Nashville, Tenn., in February 2003, five weeks before the United States invaded Iraq.

Honest people can still disagree about the ethics and wisdom of pre-emptive war, but the available evidence makes a cruel joke of the former president’s pledge. By the barest possible count—violent deaths recounted in news reports and confirmed through morgue records—the war has claimed 133,251 Iraqi civilians since March 2003. That figure alone is 28 times the toll for U.S. and allied troops, but it doesn’t fully capture the war’s humanitarian impact. The effort to topple a dictator ended up displacing 3 million people, poisoning the country’s environment, damaging water and sanitation systems, and crippling an already shaky health care system.

Modern wars always claim more civilians than soldiers, but international law has long sought to reduce civilian harm. Under the fourth Geneva Convention, an occupying power must not only secure food and medical supplies but quickly restore social and health services after toppling a government. The State Department knows this drill: during the run-up to the war, its Agency for International Development (USAID) devised a $4.2 billion plan to address the inevitable humanitarian disaster. But President Bush quietly killed that effort just three weeks before promising the Iraqi people a brighter future. In a Decision Directive dated Jan. 20, he placed the Pentagon in charge of the relief effort as well as the invasion—a move that greatly complicated the public-health response. Ten years later, the results are on full display.

The State Department started planning for a disaster in 2002, as the Bush administration raised the stakes in its standoff with Saddam Hussein. When the nation is involved in armed conflicts, USAID normally coordinates relief efforts with international groups, keeping the military at arm’s length to protect the relief workers’ neutrality. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld wanted a different arrangement for this war. He foresaw a quick campaign that would topple Saddam with minimal damage to the country’s civil infrastructure. In his dream, U.S. forces would get out quickly, and the relief organizations would step in to work directly with a new Iraqi government to rebuild. In short, we would be liberators rather than occupiers. The president acquiesced.

Dr. Frederick “Skip” Burkle is a seasoned disaster-response expert who helped direct the State Department’s planning efforts. He had managed war-related health emergencies since Vietnam, and he’d worked closely during the first Gulf war with Jay Garner, the retired U.S. Army lieutenant general Rumsfeld tapped to head his relief effort. Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney were purposely minimizing the State Department’s involvement—a source of great irritation to Secretary of State Colin Powell—but they cleared Garner to name Burkle as Iraq’s interim health minister. Burkle knew the Defense Department was hostile territory, but he still wanted the job. “I’d been in five wars and I knew how to deal with the aftermath,” he says. “I knew that wars kill civilians by knocking out water, power, sanitation and medical care. I knew we had to restore those services quickly and set up a disease-surveillance system to tell us where people were most vulnerable.”

The invasion’s shock-and-awe stage was less devastating than Burkle might have predicted; most of the country’s roads, bridges, power stations and hospitals were still intact when the initial bombing stopped. But his worst fears were realized when Saddam’s government collapsed on April 9 and the country descended into anarchy. “Widespread looting and social disorder, which had not been anticipated by the Department of Defense planners, led to destruction of public facilities and disruption of essential public services,” he would write in the Lancet a year later. “In many areas, hospitals, clinics, pharmaceutical stores, public-health departments, laboratories, and administrative offices were ransacked, causing the collapse of the already tottering health system.”

Within days of arriving in Baghdad, Burkle knew he was facing a catastrophe that the Defense Department wasn’t equipped to address. The violence was escalating and critical services were shutting down, but Pentagon officials dismissed his efforts to start a disease surveillance system. “People were dying from violence, and we were losing essential services,” he recalls. “No one was maintaining health records or death records, and I couldn’t get the support to fill the gap.” As a physician, Burkle felt he had to speak out, so he declared a public-health emergency. His relationship with the Defense Department went downhill from there. By May 12, when Ambassador Paul Bremer showed up to head the Coalition Provisional Authority, Burkle had been sent back to Washington. Garner was out too, along with Barbara Bodine, the former ambassador who’d been overseeing Baghdad and central Iraq. Burkle resigned from USAID, knowing he’d become ineffective in an administration with zero tolerance for dissent, and the administration appointed James Haveman, a Bush loyalist, to run the health ministry.

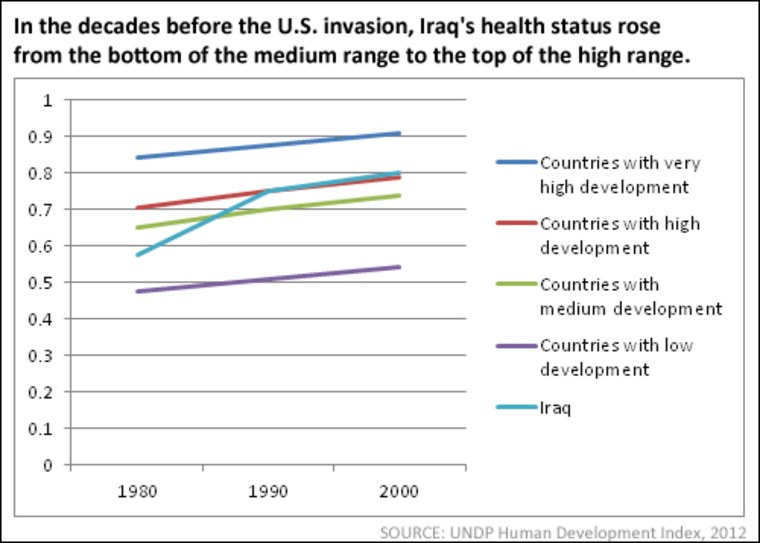

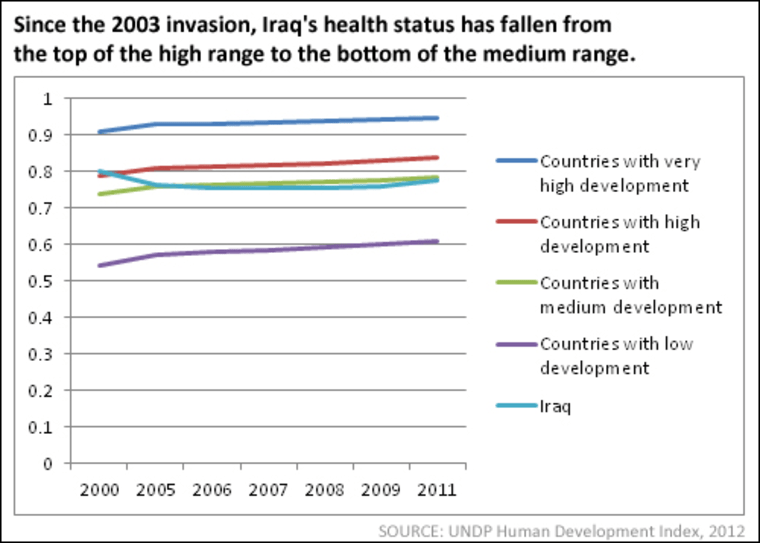

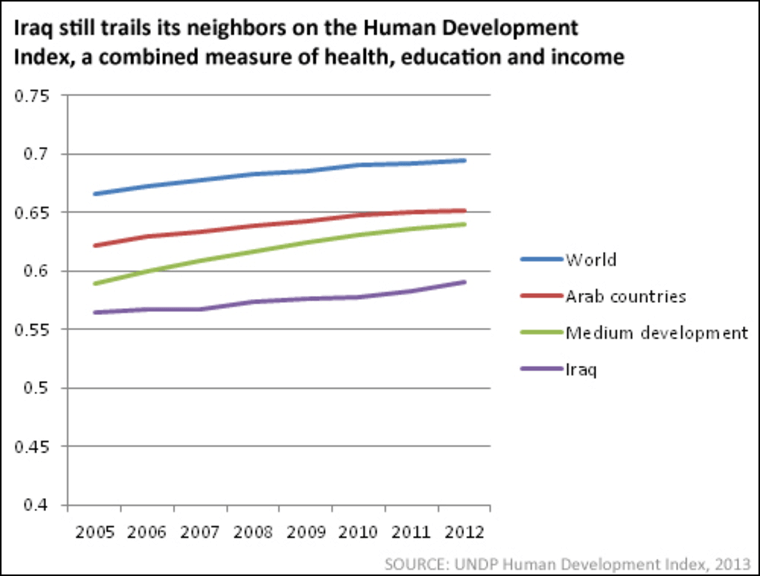

The country has come a long way since Bremer’s bitter year at the helm. Child mortality has declined slightly, and life expectancy has risen to 69 years, roughly where it stood before the invasion. But by global and even regional standards, Iraq is still struggling. In the decades before the U.S. invasion, Iraq's health status rose from C-minus levels to B-plus levels in relation to the rest of the world (chart), but the war reversed that trend. Iraq also trails its neighbors and other middle-income countries on the UN’s overall Human Development Index, a measure that covers health, education and income (chart). And though the war is now over, its indirect toll is still rising.

Estimates of the full civilian body count vary widely, but it clearly exceeds the 133,000 violent deaths confirmed from news reports and morgue records. In a 2008 study known as the Iraq Family Health Survey (IFHS), a team assembled by the World Health Organization sampled households from around the country and concluded that news reports had captured only a third of all violent civilian deaths. The IFHS also found that indirect, nonviolent deaths had increased by 60% in during the years following the invasion, just as the State Department had feared and predicted. At 2011 rates, that 60% increase would represent 81,600 excess deaths every year—the better part of a million over the course of a decade.

Death rates are just one measure of the Iraq war’s long-term impact. Here are some of the health challenges the country still faces in 2013:

Maternal and child health. Iraq’s birth rate has exploded in recent years (only a third of the country’s women have modern contraceptives), and both mothers and newborns are under duress. Anemia and pregnancy complications are common, as are low birth weight, malnutrition and stunting among children. In a 2011 survey, UNICEF and the Iraqi government found that 8% of children under age five were underweight (3% severely wasted) and 22% were stunted. Fewer than half (45%) were fully immunized during their first year, and only a fourth of those with diarrheal disease received oral rehydration therapy.

Environmental contamination. Between 2002 and 2005, U.S. forces shot off 6 billion bullets in Iraq (something like 300,000 for every person killed). They also dropped 2,000 to 4,000 tons of bombs on Iraqi cities, leaving behind a witch’s brew of contaminants and toxic metals, including the neurotoxins lead and mercury. Mozhgan Savabieasfahani, an Iranian-born toxicologist at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, is studying the health impact, and her early findings are worrying. Last year, in a study published with Iraqi colleagues, she reported staggering increases in birth defects in the heavily bombarded cities of Basrah and Fallujah. The increases started in the early 90s, after the bombings of the first Gulf War, and continued right through 2011.

In Basrah, the group’s analysis of hospital records revealed 16-fold increase in birth defects among babies delivered between 1994 and 2003 (from 1.4 to 23 per 1,000 live births), and another 48% rise between 2003 to 2009 (from 23 to 48). Likewise, a survey of 56 families in Fallujah showed a 50% increase in birth defects between 1991 and 2010, along with an eightfold increase in miscarriages. Neurological defects are now pervasive in both cities. And though the causes are still uncertain, Savabieasfahani has cited lead and mercury as likely culprits. In Basrah, she found that teeth from malformed children contained three times more lead than teeth from normal ones. In Fallujah, children with birth defects harbored five times more lead than normal kids from the same city, and six times more mercury.

“The explosion of bombs creates fine metal-containing dust particles that linger in the air and can be inhaled by the public,” Savabieasfahani wrote in an essay for Al Jazeera last week. “Metals are persistent in the environment and metal-containing fine dust may be re-injected into the air periodically as a result of wind and air turbulence. Iraq is well known for its strong and frequent sandstorms, which can easily render contaminated dust airborne. Since war debris and the wreckage from ammunition and bombs remain unabated in the environment, the weathering process facilitates continuous metal release into the environment.”

Are Basrah and Fallujah just sentinels of a wider crisis? In an initial effort to find out, the World Health Organization has helped Iraq’s health ministry sample birth-defect incidence across eight regions of the country. The survey is reportedly finished, but the findings are still under review in Baghdad. (Our calls to the health ministry weren’t returned.) Whatever the survey turns up, Savabiesfahani is deeply worried about the trends already documented in Basrah and Fallujah. “We can’t wish this away,” she says. “We need immediate efforts to identify and clean up the sources of hazardous waste. We can’t let this fester the way Agent Orange did in Vietnam.”

The brain drain. Unfortunately, the wars that spawned Iraq’s myriad health challenges have also robbed it of the capacity to address them. The country has lost more than half of its physicians since 2000 (20,000 out of 34,000), and though 1,500 to 1,800 Iraqis are now completing medical degrees each year, a fourth of them are leaving the country. Dr. Nabil Al-Khalisia, an Iraqi physician who fled to the United States in 2010, has since surveyed others in Iraq and around the world, and his findings aren’t encouraging. As he told the Lancet in an interview published last week, more than half of the doctors he surveyed in June 2011 said they had been threatened. Of those still working in Iraq, 18% had survived assassination attempts and nearly half said they still planned to leave the country.

This gutting of the health system doesn’t affect all Iraqis equally. “We do see some advances in urban areas,” says Dr. Gustavo Fernandez of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), who headed the organization’s Iraq mission from 2008 to 2010. “But services have deteriorated dramatically outside the cities. The health centers have no staff or supplies, and very few international organizations have enough security protection to work outside of major population centers.” As a result, he says, “a significant part of the population lacks the most basic health care to this day.”

To Burkle, the man who ran the Iraqi health ministry at that critical moment in 2003, what makes this all so tragic is its predictability. “State and DoD both had excellent technical staff,” he recalls. “We saw this coming, but Rumsfeld was disconnected from reality and the administration’s political people knew nothing about the region, the people, the history of armed conflict or the nature of complex humanitarian disasters.” After returning home from Baghdad and leaving USAID, Burkle briefly returned to a previous post at Johns Hopkins. But when he published his withering 2004 critique of the administration’s humanitarian response, right-wing bloggers labeled him a traitor and his Hopkins colleagues started hinting he should resign to protect the university’s good relationships with federal granting agencies. “It was a very dark time,” he says. “When I left, people assumed I must have done something horrible.”

Now in his 70s, Burkle works from home in Hawaii, where serves as a Senior Fellow and Scientist for the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and a Senior International Public Policy Scholar for the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He regrets only that the “Iraqi people” of President Bush’s grandiose 2003 speech have seen so little of the good life he promised.

Read more: Intelligence experts knew the case for war was faulty. Why didn't they speak up? And where are the architects of the Iraq war now, a decade later?