Governors are hitting major roadblocks in efforts to cast Syrian refugees as public enemy No. 1.

Still, the crusade carries on.

During the last week, state leaders have tested the boundaries of their authority in trying to block Syrian refugees from resettling in their states — and seen how little of power they actually have to pull the stunt off.

Alabama this week became the second state to take the feds to court over the anti-refugee panic. Meanwhile, Texas, which was the first to litigate the issue, was slapped back by the Department of Justice and accused of essentially trying to line-veto federal decisions. And in Georgia, one of the first states to actively try and ban refugees, leaders recently gave up the cause entirely.

RELATED: Gov. Nathan Deal withdraws order stopping Syrian refugee resettlement

Despite any apparent setbacks, these state-level maneuvers are continuing to underline the heightened panic stirred by a string of terror attacks at home and abroad. Syrian refugees found themselves at the center of the negative spotlight as people worried that America’s humanitarian goodwill could compromise national security. Around that time in November, more than 30 governors threatened to shut out refugees. Many have since been forced to abandon or tone down their approach. But with the refugee crisis maintaining strength as a major 2016 campaign topic, debate over the issue is not likely to go away anytime soon.

The states that have sued over the resettlement process, Texas and, as of Thursday, Alabama, argue that the Obama administration violated refugee laws enacted back in 1980. State officials claim that because they were not consulted in decisions over where Syrian refugees should be placed to live, states have grounds to sue.

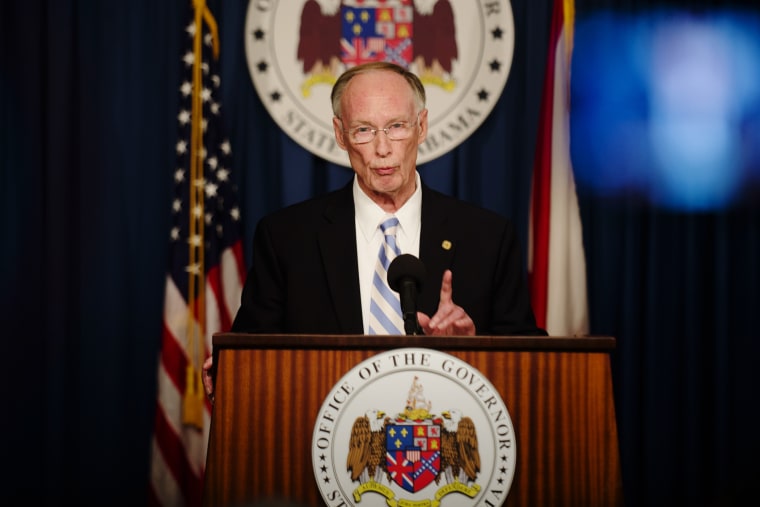

“My number one concern is the safety for the people of Alabama and making sure an outdated, archaic and dangerous process that excludes the states is eliminated,” Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley said in a statement Thursday.

The Obama administration instead is calling the move out as political bluster. In legal filings this week opposing the Texas lawsuit, the Justice Department said claims that terrorists could infiltrate the refugee system and harm the U.S. were based on “hearsay, and are at best speculative.”

Refugees undergo a rigorous vetting process that typically starts with the United Nations, goes through as many as five levels of federal screening, and ends, on average, 18 months later. President Obama has called for the U.S. to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees. The country has taken in only a few thousand since civil war broke out in Syria, and they have been resettled all across the country.

Even if governors could override federal migration policies — which the Obama administration says they can’t — they would run into a number of practical issues in trying to ban refugees. Mainly, the government doesn’t track people and their whereabouts. There’s nothing to stop people from being settled in one state and later moving to another.

Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal saw the writing on the wall this week. He had issued an executive order last November declaring that state agencies must cut off any involvement with the federal resettlement process. But a month later, the state’s Attorney General Sam Olens, who is also a Republican, had to publicly remind the governor through an official court opinion that he didn’t have the executive authority to outright ban the refugees or deny them federal benefits.

Deal responded on Monday by quietly rescinding the executive order.