Forty-three years ago, a group of leftist activists broke into an FBI office outside Philadelphia -- what they uncovered was evidence of a massive spying and political influence operation deployed by the bureau against American citizens.

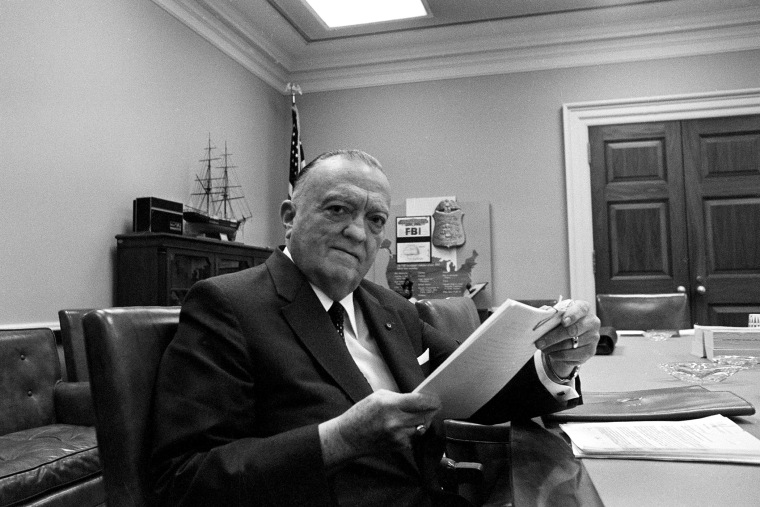

Before the 1971 break-in drew attention to the FBI's activities, Americans didn't know that J. Edgar Hoover, the infamous leader of the FBI for 48 years, had implemented a program called "cointelpro" designed to infiltrate and discredit critics of the U.S. government, not just terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan but anti-war protesters and civil rights activists. They didn't know that Hoover had tried to blackmail Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. into committing suicide, that Americans were being spied on simply because of their political beliefs, or that government agencies were systematically breaking the law in the name of national security. As Tim Weiner wrote in his history of the FBI, before President Lyndon Johnson directed Hoover to deploy his resources to destroy the KKK, Hoover considered the Klan's campaign of murder and terror to be of far less concern than black people fighting for their full rights as American citizens.

The activists who committed the break-in were never caught--and have only now come forward as part of a book and documentary project focused on the event.

“We did it … because somebody had to do it,” one of the activists, John Raines, 80, a retired professor of religion at Temple University, told NBC News. “In this case, by breaking a law -- entering, removing files -- we exposed a crime that was going on. … When we are denied the information we need to have to act as citizens, then we have a right to do what we did.” The break-in, and subsequent revelations by journalists based on the materials from the break-in, led to the congressional Church Committee that reined in government spying and set up the current system of congressional oversight.

With the activists coming forward just six months after former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents revealing the scope of the NSA's data-gathering programs, there are bound to be comparisons. After all, technology has made the surreptitious break-ins and wiretaps of the Hoover era obsolete. Instead of sending King a threatening letter, Hoover might have just put audio recordings of King's infidelity on YouTube.

If the activists who broke the law by burgling the FBI were justified because they exposed much larger campaign of lawbreaking by the government, then wasn't Snowden also justified in exposing the nature of NSA surveillance, given that government officials had deliberately tried to mislead the public about the agency's activities?

Snowden's critics might counter that, no matter how broad the scope of NSA spying, how impressive their technological capabilities, or how eroded our modern conception of privacy has become, his leaks have not yet shown a massive, deliberate campaign of political suppression by the U.S. government aimed at its own citizens.

But does that mean Americans should wait until that happens before doing something about it?