NEW ORLEANS – On Monday morning, a federal appeals court will hear arguments in the challenge to a Mississippi law that would close the last abortion clinic in the state. What’s at stake stretches far beyond Mississippi.

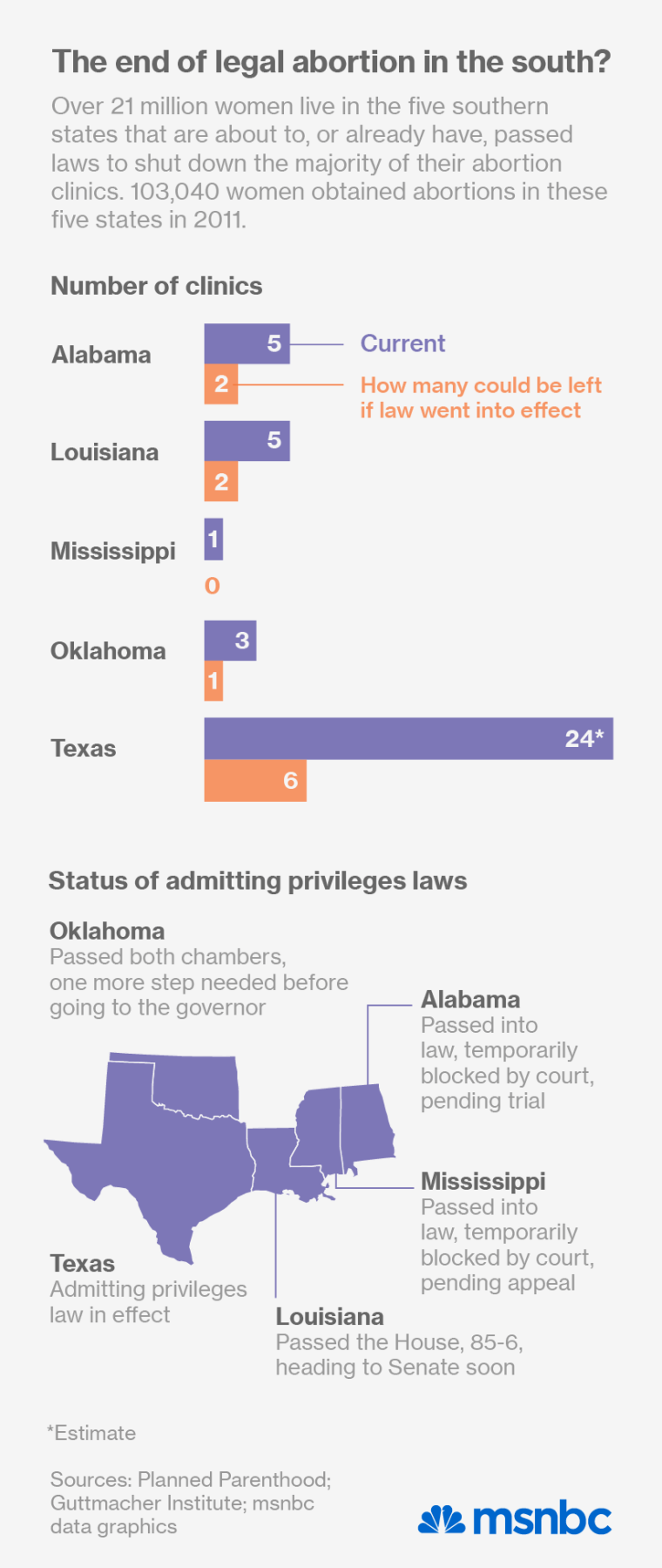

The same law that threatens to end legal abortion in Mississippi has swept across southern states, leaving women there with waning alternatives. Unless the federal courts step in, access may be decimated in a vast swath of the country, potentially closing three-quarters of the abortion clinics in states where 21 million women live. And so far, those courts have been decidedly divided on the constitutionality of such laws.

The Mississippi law in question sounds innocuous. It requires that abortions be provided by doctors who are board-certified obstetrician-gynecologists, and that they have admitting privileges at local hospitals. But in Mississippi and elsewhere, local hospitals have refused to provide those privileges, which the medical establishment say aren’t medically necessary. Indeed, the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have said such laws are worse than unnecessary: They “impose[s] government regulation on abortion care that jeopardizes the health of women.”

Mississippi politicians have hardly hid the intentions behind the law. Before he signed the law, Governor Phil Bryant said he would "work to make Mississippi abortion-free."

Under binding Supreme Court precedent in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey, states cannot impose an “undue burden” on a woman’s constitutional right to end her pregnancy before the fetus is viable. “Constitutional rights in this country do not depend on your zip code and where you live,” said Bebe Anderson, director of the U.S. legal program for the Center for Reproductive Rights, which represents Jackson Women’s Health, the Mississippi clinic.

But in practice, “undue burden” has been a slippery concept, and in the hands of some conservative judges, it has been almost meaningless. The judges on the appeals panel Monday include two Republican appointees, including Emilio M. Garza, who has repeatedly disagreed with the Supreme Court that there is a constitutional right to an abortion. The third judge, Stephen A. Higginson, was appointed by President Barack Obama.

Even as the state may be left with no clinics, all around Mississippi, abortion access is crumbling. Since a panel from the same Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed a similar law to go into effect in Texas late last year, one-third of the clinics in that state have closed. If the courts don’t block a requirement to turn clinics into mini-hospitals, which they’ve also been asked to do, the total number of clinics will drop down to six in September. To the east of Mississippi, a court has temporarily prevented Alabama’s version of the law from closing three out of five of the state’s clinics, but a trial is pending. Meanwhile, admitting privileges laws have easily passed one chamber in Louisiana and both chambers in Oklahoma, and unless the politics change overnight, are expected to become law. According to Planned Parenthood, those laws would close three of five of Louisiana’s abortion clinics, including here in New Orleans, and two out of three of Oklahoma’s. In 2011, women in those five contiguous states -- Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma -- had a total of 103,040 legal abortions, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Such laws would have the effect long desired by social conservatives: To end legal abortion, if not the need or desire for it. The difference is that now the anti-abortion movement has both willing state legislators and, at times, willing federal judges.

Decades ago, Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of Roe v. Wade, grimly predicted such an outcome when the Supreme Court began allowing more and more restrictions on abortion. “If a right is found to be unenforceable, even against flagrant attempts by government to circumvent it,” he wrote in a 1991 dissent, “then it ceases to be a right at all.”

A year later, the Casey decision was famously crafted by the court’s moderates as a middle ground. Rather than overturn Roe v. Wade entirely, the plurality said states could restrict abortion as long as it didn’t have “the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion.” Priscilla Smith, director of the Program for the Study of Reproductive Justice at Yale Law School who argued two abortion cases before the Supreme Court after Casey, recently wrote that “the resulting doctrine is a mess, creating rampant confusion and decisions at odds on theoretical and practical levels.”

The decisions on the admitting privileges laws exemplify that discord, though lower courts have generally blocked the laws. In the Mississippi case being heard today, District Court Judge Daniel P. Jordan, a George W. Bush appointee, blocked the law from taking effect because he said it would “nullify over 20 years of post-Casey precedent.” He added, "The state's position would result in a patchwork system in which constitutional rights are available in some states but not others." And in March, District Court Judge Myron Thompson wrote in temporarily blocking the Alabama law: "Countless factors, including the lived experience of the actual woman who will be affected, may affect whether a given regulation does or does not create a substantial obstacle in the real world." If the law was meant to stop abortions from happening, Thompson wrote, "it operates only through coercive means, specifically by closing down clinics or limiting their capacity."

In a December decision on Wisconsin’s admitting privileges law authored by Judge Richard Posner, the Seventh Circuit plainly declared that in considering an "undue burden," it mattered whether restrictions on abortion clinics were grounded in actual evidence: "The feebler the medical grounds, the likelier the burden, even if slight, to be undue."

But in March a three-judge panel in the Fifth Circuit looked at the same law in Texas -- which had similarly been blocked by the district court -- and shrugged off the burdens on women, including driving an additional 250 miles to a clinic. At oral argument, Judge Edith Jones suggested the women simply drive fast. (Many of the women in question lack the resources to make the journey, or fear immigration checkpoints en route.) In the highest-level decision upholding an admitting privileges law yet, Jones wrote of the Texas law that “a legislative choice is not subject to courtroom fact-finding and may be based on rational speculation unsupported by evidence or empirical data.’” In other words, the state can come up with any trumped-up excuse for a law it wants, even if that law infringes on what the Supreme Court has repeatedly held to be a constitutional right. “Rational speculation” is a decidedly new, far lower bar for scrutinizing an abortion law, and the Texas clinics have appealed to the full Fifth Circuit.

Of the Casey authors, only Justice Anthony Kennedy is still on the Court, and pro-choice advocates aren’t sure they can count on him, especially with the broader court having lurched rightward. That leaves a series of unappealing options on the table -- appealing the admitting privileges laws all the way to the Supreme Court and possibly getting a result that dilutes abortion rights even more, or letting Roe be practically gutted on the ground. (The state of Wisconsin has appealed to the Supreme Court over the temporary blocking of its admitting privileges law, but since a trial is expected in May, it is likely the Court will wait for the lower courts to hear the case in full. The Court declined to stop the first part of the Texas law from going into effect.)

"At some point,” wrote Judge Thompson in Alabama, “the obstacles on the right to obtain an abortion will become so significant that the State cannot justify them at all." Where is that point? The women of the South are about to find out.