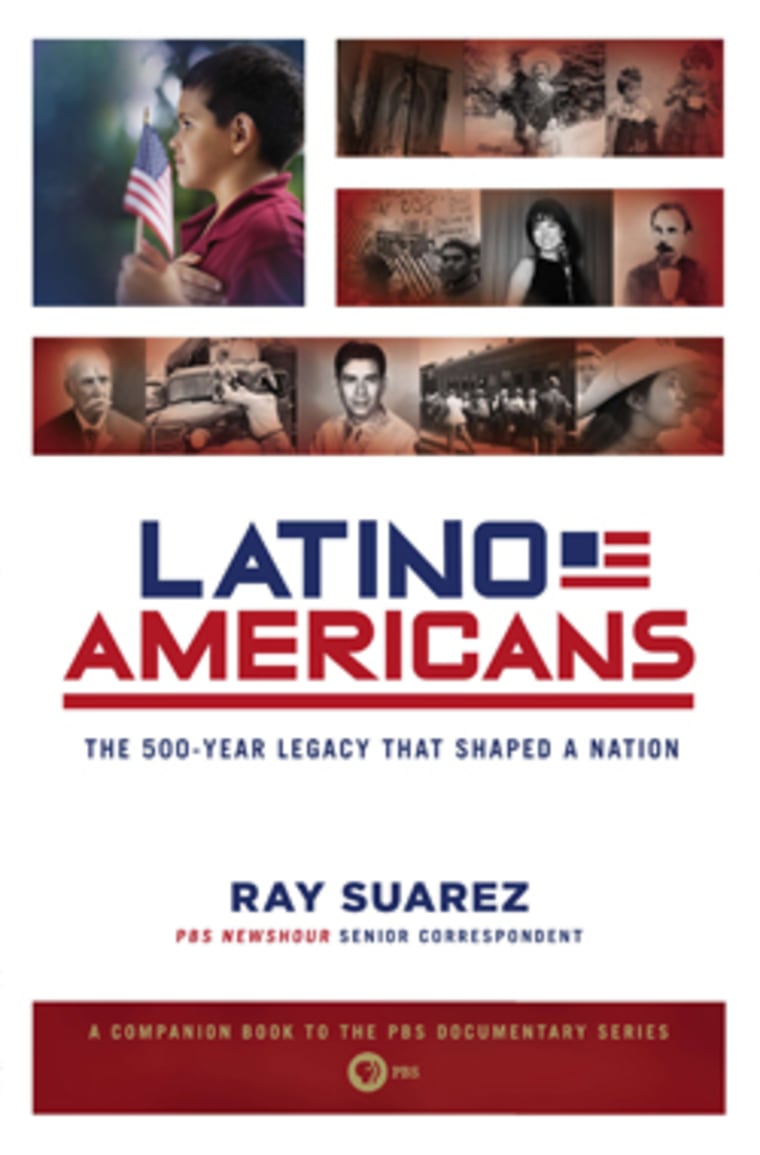

Here's an excerpt of Latino Americans.

Every nation has an origin story. It’s the story they tell themselves, about themselves, to understand who they are.

Americans are no different.

In many ancient civilizations, the origin story ties a people so intimately to the land that they are made out of it, molded by a creator from the literal soil of the place. The Japanese, the Menominee Indians of the Great Lakes, the Yoruba of West Africa, all have creation stories that tie the people and their history directly to the land. There is no memory of another place. In their telling, they have existed along with the land, and had no life apart from it.

Americans are very different.

Our origin story has to bring almost all of us from someplace else on the planet. So where does the story of the United States of America begin? Some of you might say Plymouth Rock, the spot on the damp New England shores where the Pilgrims are said by tradition to have come ashore from the Mayflower in 1620.

Others might say Jamestown, some six hundred miles to the south, where in 1607 Englishmen in search of fortune, not fleeing religious persecution, began probing the sandy inlets and started spinning gold from tobacco.

This country was not just a creation of the British Empire, however. There were five hundred nations in North America before a European ship ever dropped anchor off the Eastern Seaboard. Once Europeans started coming over in ever greater numbers, the territory that is now the United States became home to many colonies.

The Dutch made their way up the Hudson River and settled in the breathtakingly beautiful valleys of what is now Upstate New York. At the mouth of the river, Dutch farms and trading houses spread over the tracts of land around the great harbor that became New York City. The Swedes tried to make a go of colonization in parts of what is now Delaware and Pennsylvania. Even the Scots, before becoming part of the United Kingdom, attempted to plant colonies in what is now Maritime Canada, New Jersey, and the Carolinas.

France’s North American empire stretched across a vast and rich swath of the continent many times the size of the parent country, including what is today half of Canada, and the U.S. Midwest, Great Plains, and Pacific Northwest. In the far northwest, the expanding Russian Empire pushed east, crossing the Bering Strait, colonizing Alaska, and moving down the coast of what is now Canada’s British Columbia toward what would one day be Seattle. The Russians began to probe even farther south to what is now northern California.

The Genoese sailor sent west by Ferdinand and Isabel of Spain, Cristoforo Colombo in Italian, Cristóbal Colón in Spanish, and Christopher Columbus in English, made multiple trips to the Caribbean, and began four centuries of Spanish presence in the hemisphere. Looking for “Cathay,” China, he began the creation of an enormous New World empire for Spain.

The empire belonged to Their Most Catholic Majesties the king and queen of Spain. Pull out a map and take a look at South America, where Spain’s possessions included virtually all the continent outside Brazil, all of today’s Central America and Mexico, and all or part of Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho, North and South Dakota. At its height in the last years of the eighteenth century, Spanish territory stretched as far north as the southern lands of what are today the prairie provinces of Canada, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

So where does the story of the modern United States begin? On Plymouth Rock, sure, but not just there. . . .

In Virginia, sure, but not just there. . . .

It turns out there are many candidates for the origin point, a place to visit like the coasts of Virginia or Massachusetts and say, “It all starts here.”

Forty-two years before the men of the Virginia Company of London began to pound the fort at Jamestown into place, and fifty-five years before seasick Protestant refugees stepped onto dry land from the Mayflower, a Spanish sailor named Pedro Menéndez de Avilés dislodged French Protestants from their settlement on the Florida coast and established St. Augustine.

The Florida city is today the oldest continuously occupied European city in the United States. From 1565 to 1821, St. Augustine, San Agustín, was a Spanish-speaking city. As European empires fought their wars in the New World, the Florida city lived under different flags, but it was essentially a Spanish place for three centuries. The next time a tense local controversy breaks out in Florida over the use of Spanish, take a second to recall how much longer that tongue has been at home in the state than that relative newcomer, inglés.

Across the face of this vast continent, the empires moved and probed and jostled and searched. They spent more than two centuries moving their frontiers toward each other, and fighting wars over the bountiful land. The boundary lines shifted and crossed, and eventually disappeared. By the mid–nineteenth century, as the dust cleared from the Mexican War, the shape of the modern continental United States emerged. What had been French and British and Spanish territories now flew under the flag of the United States.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.