Mohamed Farah was an hour late.

Once more, I scanned the dimly lit plaza trying to spot him. Maybe he was hiding somewhere, watching us, making sure we had indeed come alone.

I tried to make out the faces of the young men smoking in front of Istar Restaurant, a popular halal joint where diners could see out but you couldn’t see in. None of them looked familiar.

Maybe he was inside? It was about 10:30 P.M. Our car was parked at the far end, in front of a bank, as instructed.

“God, he better show up this time,” I said to my colleague Kevin Donovan.

This would be our third attempt at seeing the video.

It had been a month, almost to the day, since Farah called me on my cell phone with a cryptic news tip. It was 9 A.M. on Easter Monday 2013, and I’d been trying to sleep in. I shuffled out of bed, irritated that someone was calling so early on a holiday.

“Robyn speaking,” I said.

“Robyn Doolittle, from the Toronto Star?”

I didn’t recognize the man’s voice. It was deep and had that nonchalant drawl that young cool guys tend to use.

“Yep. Who am I speaking with?”

“I have some information I think you’d like to see,” he said. “I don’t want to talk about it on the phone … it’s about a prominent Toronto politician.”

A week earlier, I’d co-written a controversial piece with Kevin Donovan about the mayor of Toronto’s struggle with alcohol. I suspected the caller was talking about Rob Ford.

He claimed to be in possession of a very incriminating video, but he refused to say anything more on the phone. He wanted to meet as soon as possible. “I’ll come to you,” he offered.

That was encouraging. If he was willing to make the trip, odds were he wasn’t completely without credibility.

Shortly before noon, I arrived at a crowded Starbucks in a hipster neighbourhood just outside of downtown Toronto.

“Robyn?”

I spun around to see a clean-cut East African–looking guy who seemed about my age, somewhere in his late twenties, maybe early thirties.

“I’m Mohamed,” he said, extending a hand.

He was thickly built, like a football player, and a good head taller than me, wearing a button-up shirt and dark baggy jeans that had a bit of a shimmer to them—hip hop meets business casual. We headed to a nearby park and settled on a bench by the soccer field.

Farah told me he volunteered with Somali youth up in Rexdale—a troubled neighbourhood in Toronto’s northwest end not far from where Ford lived—and that he’d read my story about the mayor and alcohol.

“It’s much worse than that,” Farah said.

I knew this was true. For a year and a half I’d been investigating whether the mayor had a substance abuse issue. To an outsider, what Farah said next might have sounded unbelievable.

But not to me.

“The mayor is smoking drugs. Crack cocaine.” Farah searched my face to see if I believed him, but I kept a blank expression. “And I have a video of it.”

“Did you bring it?”

“I can’t let you see it yet. But I brought this.” He pulled out a silver iPad.

He thumbed around for a few seconds, then turned it towards me. There was a photo of Ford, grinning and flushed, his blond hair matted and messy, with three men who looked to be in their early twenties. Ford, who was wearing a baggy grey sweatshirt, had his arms around two of them. One of the guys was making a “west side” gesture. Another in a dark hood was flashing his middle finger while gripping a beer bottle. It was shot outside at night. The group was standing in front of a yellow-brick garage with a big black door. There was snow on the ground.

Was this photo part of the video?

No, Farah said, but it showed the mayor in front of a crack house with men connected to the drug trade. And “that one,” he continued, pointing to the hooded man with the beer bottle, “is Anthony Smith. He was killed outside Loki nightclub last week.”

Farah had my attention.

He put the iPad away and the conversation returned to the video. Farah claimed the footage was shot by a young crack dealer. He swore that it clearly showed the mayor inhaling from a crack pipe, complaining about minorities, and calling Justin Trudeau, the leader of the federal Liberal Party, “a fag.” Farah alleged that his friends had been selling drugs to the mayor for a long time, but Smith’s death had everyone scared. The dealer wanted out. He wanted to move to Alberta and start over. Farah told me he had agreed to help.

Here came the catch.

They wanted a hundred thousand dollars for the footage.

THAT WAS thirty-three days earlier.

Now, I was waiting in a grungy plaza parking lot in a bad part of town with Kevin Donovan, passing the time by theorizing what was going to happen—if anything. Would they show us the video right there in the car? Would it be a group of people? Or just Farah and the dealer? What if they wanted to drive us somewhere?

The later it got, the more I was convinced we were waiting for no one. Then out of nowhere a black sedan pulled up beside us. It was Farah. He wasn’t getting out of the car. He phoned me from feet away. “Leave your cell phones. No bags. No purses. And get in.”

I sat in the front. Donovan climbed into the back. Farah was breathing quickly. He didn’t say anything as we turned left onto Dixon Road, a busy street in a part of Toronto called Etobicoke. A few minutes later, he pulled into a dark parking lot behind a six-tower condo complex that looked worse than some subsidized housing in the city. We parked behind 320 Dixon.

Farah called his guy. “He’s coming,” he told us.

A skinny Somali-looking man in a wrinkled black T-shirt appeared out of the darkness. He got in the back with Donovan. I guessed he wasn’t much older than twenty-five. He had a peculiar look about him, his face sort of caved in on itself, with his eyes, nose, and mouth squishing together between a large forehead and pointy jawline. His black hair was cut close to his head, and his arms were pocked with thick scabs. Donovan and I introduced ourselves, but he didn’t want to talk and never gave his name. He pulled out an iPhone and hit play.

I thought I was prepared, but I couldn’t hide my shock.

There was Rob Ford—and there was no doubt in my mind that it was Rob Ford—the mayor of the fourth-largest city in North America, slurring, rambling, wobbling around in his chair, sucking on what looked like a crack pipe.

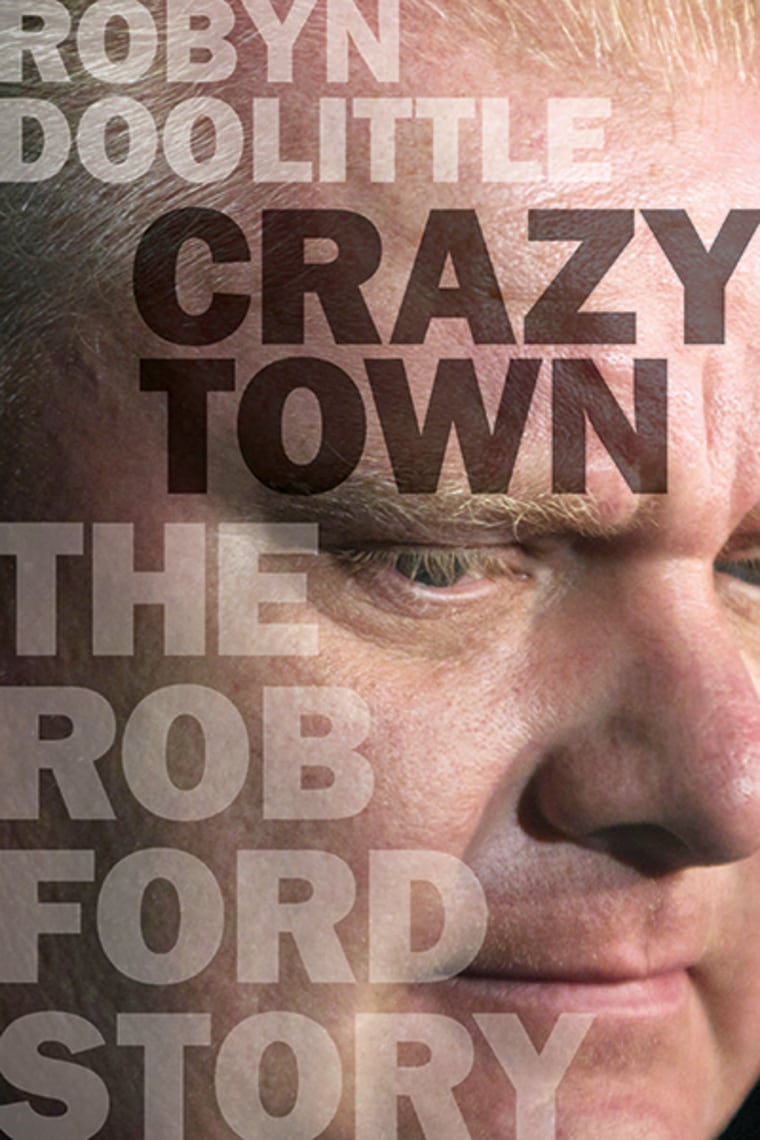

BEFORE BECOMING MAYOR on December 1, 2010, Rob Ford had spent ten years as a controversial city councillor. His checkered past included a drunk driving conviction, a domestic assault arrest (which was later dropped), and allegations of racism and homophobia. But Ford’s antics had rarely earned ink outside of the Greater Toronto Area, and even two and a half years into his term as mayor, it was unlikely the average Canadian would have recognized him on the street. That would all change on May 16, 2013. That was the night the American gossip website Gawker posted a story with the headline “For Sale: A Video of Toronto Mayor Rob Ford Smoking Crack Cocaine.” The Star published a few hours later. By week’s end, Ford was on his way to becoming internationally infamous, a running gag on American late-night television, and the subject of one of the most astonishing political scandals in the country’s history.