Moscow, Red Square, May 24, 2003 As the sun slides behind the Kremlin, a hundred thousand people pack into Red Square, into the heart of Russia. The fairy-tale domes of Saint Basil’s cathedral and the ancient red walls of the Kremlin seem to be on fi re. The vast crowd roars— and many weep— as a familiar figure strikes the first chords. “Back in the U.S.S.R.” rolls out across the square— and Paul McCartney is here at last to sing it.

“People cried rivers and waterfalls of tears,” says Artemy Troitsky, Russia’s celebrity rock guru. “It was like something that sums up your whole life.” “Moscow girls make me sing and shout,” sings McCartney, and the crowd sings back, laughing, crying, hugging, dancing to an anthem that had once put some of them in jail, lost them their jobs and their education, turned them into outcasts. Now the Soviet Beatles generation, the kids of the 1960s and the de cades of stagnation, are gathered to welcome a real live Beatle. “It was as if the mystical body of the Beatles came to the middle of Moscow,” says Sasha Lipnitsky, who has been waiting for more than forty years.

The story of how that Red Square spectacular— unimaginable for decades— finally came to pass is an extraordinary, untold tale. It’s the story of how the Beatles changed everything back in the U.S.S.R. and turned a world upside down. It is also the dramatic and troubled history of popular music in the Soviet Union. During seventy years of totalitarian rule in a society where culture always had the power to drive change, exotic Western imports— jazz, dance music, bards with a message, rock ’n’ roll— had a seditious force. For de cades before the Beatles became a catalyst for change, popular musicians and their music had alarmed Soviet leaders, triggering bizarre wars between guardians of official culture and the generations of musical rebels who insisted on dancing to a different tune.

Unrecorded in accounts of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the impact of the Beatles— and the musical revolution they inspired— were crucial in washing away the vast totalitarian edifice. Their music, their style, their spirit were the keys. They were forbidden, never allowed to play in the U.S.S.R. But their music was irresistible. It blasted open the door to Western culture, fomenting a cultural revolution that helped to destroy the Soviet Union.

Now, the Soviet Union was gone and a Beatle was playing in Red Square. Down in the front row of the audience were Putin and Gorbachev and the bosses of the new Russia, inheritors of the men who once ran the KGB and the vast Soviet empire, the men who had called rock ’n’ roll “cultural AIDS” and banned the Beatles. Now the heirs of those repressive old men who had stood on Lenin’s tomb gazing out on the armies and the missiles parading through this same Red Square were tapping their feet to “Can’t Buy Me Love.”

Stalin and Brezhnev and all the others buried in the Kremlin walls could never have imagined this night. They were men whose mission was to turn culture into politics, and create Soviet culture. “The Party couldn’t give the kids anything,” said Art Troitsky. “There was nothing that reminded me of my dreams.” Official culture meant men with bad haircuts belting out patriotic anthems at beefy matrons in cardigans, dancing bears, and massed choirs of soldiers.

It had been in the mid- 1960s that the music fi rst reached the Beatles generation, gathered now in Red Square. By stealth, by way of gossip and whispers, through the illicit late- night broadcasts on Radio Luxembourg, the BBC, and Voice of America, the kids tuned in. “Bitles,” they whispered. “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

As a generation of Soviet kids dared to sing along, they gave up on “building Socialism” and abandoned the beliefs of their parents. “The Cold War was won by the West,” says Troitsky, “not by nuclear missiles, but by the Beatles.”

Sitting near Artemy Troitsky to hear Paul McCartney in Red Square was Kolya Vasin. The bear- shaped Vasin is Russia’s ultimate Beatles fan, a man who insists his soul was saved by finding the Beatles. “My soul flew to the light,” he says, recalling the first time he heard them, “flying with the Beatles.” Like so many Soviet kids who defected into their own world, he found a private refuge of peace and love and music. Exiling himself in his own tiny apartment from the repressive realities of the Soviet state, Vasin had created “the John Lennon Temple”—“the only place where I could feel like a free man.” Today he dreams of expanding his temple into a vast tower on the edge of Saint Petersburg.

Vova Katzman had made the pilgrimage from Kiev to be here. As a boy, he had defied police and parents to keep the faith with the Beatles. Now he ran Kiev’s Kavern Club, a bar crammed with Beatles memorabilia where devotees from across Ukraine and beyond gathered to swap stories of old battles under the banner of the Fab Four. Being here in Red Square, Vova said, “was like a fable— something fantastic.” He struggled to fi nd words. “I was shivering deep inside.”

Andrei Makarevich was here, too. At school thirty years earlier he had decorated his books with Beatles drawings, and dreamed of starting a band. “Just get a guitar, play like the Beatles, and the world would be smashed.” For Makarevich, the dream came true. His band, Time Machine, became the biggest group in the U.S.S.R.— and eventually they were to record at the Beatles’ Abbey Road Studio in London.

The Beatles generation were gathered that day in Red Square, many of them grandpas and babushkas now, many who had waited de cades, from the very fi rst whispers of the names John, Paul, George, and Ringo— from that moment when they knew there was something else.

Kolya Vasin told me that he had first seen moving pictures of the Beatles forty years ago in a black- and- white clip filmed in Liverpool’s Cavern Club, a grainy piece of ancient history. I told him I made that little fi lm, and his face glowed. “You are great man!” he roared.

For me, it all started with that film. Back in August 1962 I made a two- minute cameo of four unknown kids bashing out rock ’n’ roll in a Liverpool cellar. Soon the Beatles were conquering the world. But it wasn’t until twenty- five years later in Russia that I began to hear stories— incredible at first— about how those lads I first heard in the cellar had undermined the Cold War enemy.

Over more than two de cades of traveling and filmmaking as the Soviet Union collapsed and the new Russia was born, I pursued stories of how the Beatles rocked the Kremlin. Everywhere, I found traces of an improbable but unstoppable epidemic, spawned by the Beatles and their music, which swept through the Soviet Union and helped to destroy Communism. Along the way, I came upon the story of how a superpower struggled for seventy years to control Soviet music; and how finally the state lost its hold on millions of kids who escaped into their own world to dance to the music of four irreverent rockers from England.

I found confirmation of the Beatles’ impact in unexpected places. An academic at the austere Institute of Russian History insisted that “Beatlemania washed away the foundations of Soviet society,” adding, “They helped a generation of free people to grow up in the Soviet Union.”

As I got deeper into my journey, I wondered from time to time why I was so obsessed with the Soviet Beatles revolution. Why did it feel so haunting, so personal? There was that little fi lm, of course, and there were my first encounters with the Fab Four long ago. There was the fact that I learned some Russian during my military service as a junior spy back in the 1950s. But underlying all that, for me— a child of the Cold War— the pull was that the story felt like an essential narrative of my times. The standoff between East and West split the world, and nuclear oblivion seemed a real possibility. I remember wondering one night in October 1962 during the depths of the Cuban Missile Crisis if I would wake up the next morning. But somehow the Cold War didn’t boil over, and the austerities of the postwar world began to relax. Better times were driving change everywhere across the West; and the soundtrack was rock ’n’ roll.

From the early 1980s, I began to work in the Soviet Union and the Soviet satellites of Eastern Europe, spending time in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Yugoslavia— as well as in Russia— all still under strict authoritarian control. As I came and went— often unofficially— I met up with those kids who made the Soviet Beatles revolution. In the mid- eighties I hung out with nervy rock dissidents in Leningrad and Moscow; in the nineties I journeyed through the messy liberations of post- Communist Russia where the Beatles music was legal at last in a gangster state. Over the past de cade, I followed the story to the outer edges of Russia, seven time zones east of Moscow in the once- closed city of Vladivostok. I tracked down Beatles true believers in the chaotic new states of Ukraine and Belarus, where fourteen year- olds and their grandparents still insisted “All you need is love.”

Their stories of how it was for them back in the U.S.S.R. are wild and funny, scary and farcical, and foolishly brave. Their memories of doing battle with the crazed repressions of official culture also chart the final acts of the huge Soviet epic.

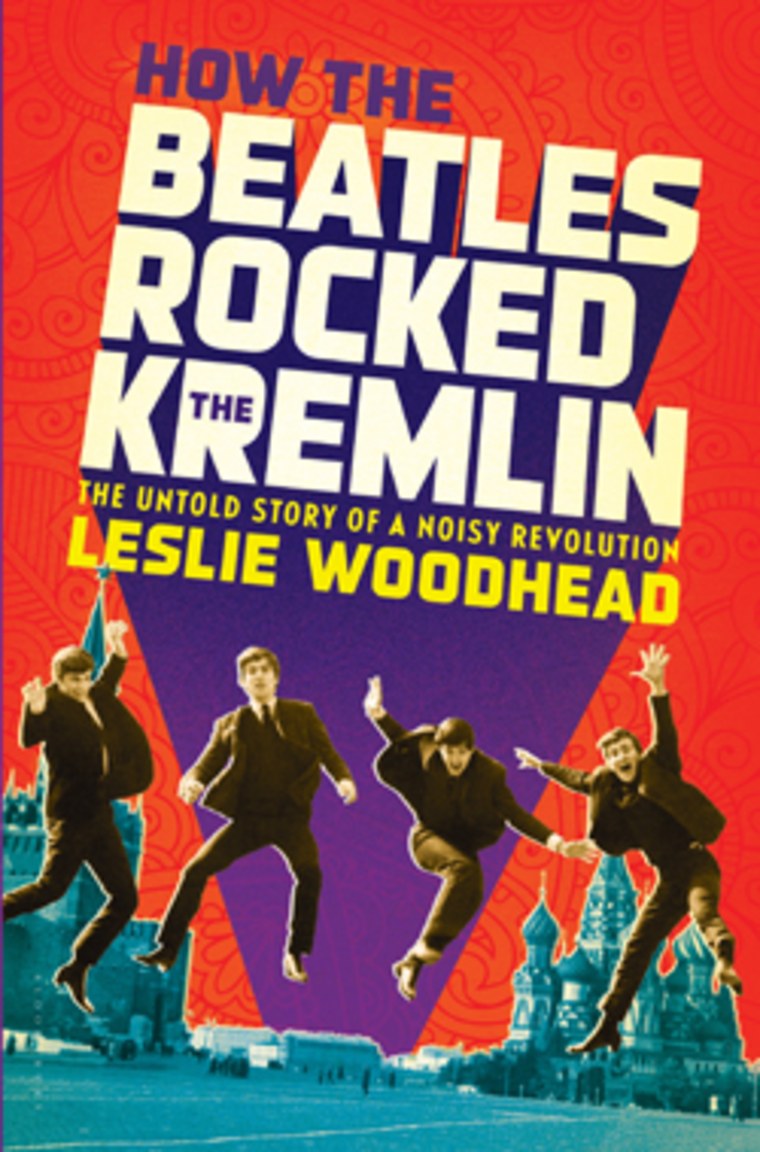

Reprinted from In How The Beatles Rocked the Kremlin. Copyright © 2013 by Leslie Woodhead. Used by permission of Bloomsbury USA.