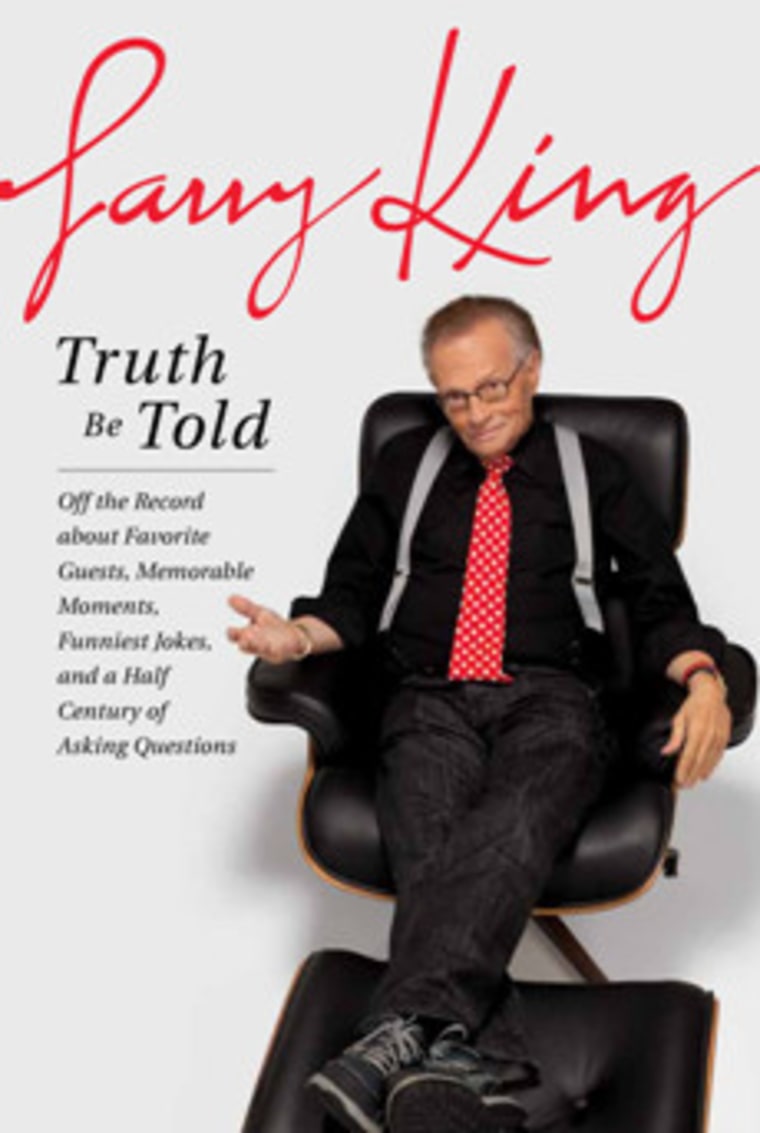

Larry King was on the set of Morning Joe Tuesday to talk about his career, his favorite interviews, and new book, "Truth Be Told." Watch the video.

Read an excerpt of the book, below.

Time

I’ve never thought much about time, because I’ve always been too busy looking at my watch.

That sounds like something Yogi Berra might say. But it’s true. You can’t be a broadcaster without being extremely con- scious of the clock. I’m never late. I remember a time after I had heart surgery. I was at the La Costa Resort, waiting for my surgeon to meet me so we could head to the airport. I said, “Jeez, where is he?” Somebody who knew him said, “He can be late. He’s a surgeon. Surgery doesn’t start without him.”

A broadcaster cannot be late. Well, he can. But he’ll be fired. For fifty-three years, my day has been planned around six o’clocks and nine o’clocks. It’s hard to explain how conscious of the clock that makes you. I can only give you a sense.

Not only are you always conscious of the hour when you’re in broadcasting, but you also have a heightened awareness of seconds. When you’ve repeatedly got to slide into a commercial break, you understand exactly how long five seconds lasts.

I used to have a cheap little clock on the set of Larry King Live. Every time Jerry Seinfeld came on as a guest he’d swipe it. It wasn’t a case of: The show’s over, here’s your clock. He’d never give it back. I’d have to go to Radio Shack and buy another.

“Jerry,” I finally said—after he took it for the third time. “Give the clock back.”

“You don’t need it,” he said. “You’ve got a clock in your head.”

He was right. But the strange thing about the clock in my head is that it always seems to be in the future. This is how it feels: Just say there’s a miracle and I landed an interview with God on Monday night. It’d be on the front page of every news- paper: LARRY KING TO INTERVIEW GOD MONDAY. You know what I’d be thinking? What am I going to be doing on Wednesday night?

For fifty-three years, that’s the way my mind has worked: thinking about what’s next and constantly checking my watch to make sure I’m on time for it. But that’s very different from stopping to think about time and the meaning of its passing.

As my CNN show wound down the last two weeks of its twenty-five-year run, a moment came that made me stop to reflect. During the final minute of a satellite interview with Vladimir Putin, the Russian prime minister invited me to Moscow. Then, through his interpreter, he turned the tables on me.

“Can I ask you one question?” “Sure.”

“In U.S. mass media,” he said, “there are many talented and interesting people. But, still, there is just one king there. I don’t ask why he is leaving. But, still, what do you think? We have a right to cry out: Long live the King! When will there be another man in the world as popular as you happen to be?”

I’ve never taken compliments well, and my head dipped. It’s OK in broadcasting to look down at your notes for an in- stant. But your eyes can’t become glued to your desk. My head just wouldn’t come up. I doubt many broadcasters have been faced with a similar situation. It wasn’t a mistake. A reaction isn’t a mistake. I was humbled.

For the first time since May 1, 1957, I was speechless. That moment with Putin connected me to my first moment on the air.

As I lowered the music to my theme song in the control booth of a tiny radio station in Miami Beach, my mouth felt like cotton. I couldn’t introduce myself. I opened my mouth, but no words came out. WAHR listeners must have wondered what the hell was going on when I took up the theme song again and lowered it once more. Again, no words came out. Maybe the audience could hear the pounding of my heart—but that was about it. I took up the theme song again, then brought it down for the third time. Nothing. That’s when the station manager kicked open the control room door and screamed: “This is a communications business!”

It was as if he grabbed me by the shoulders and shook the words out of me. I told the microphone how all my life I’d dreamed of being a broadcaster. I told it how nervous I was. I told it how the station manager had just changed my name a few minutes earlier and then kicked open the door. I let my- self be me, and the words started flowing.

So my career had started with an awkward moment of speechlessness. I couldn’t believe I was actually on the air. And now my television show was approaching an end with another speechless moment. The prime minister of Russia has just called me a king.

The same lesson I learned on my first day guided me through the awkwardness fifty-three years later: There’s no trick to being yourself.

My head came up to look at Putin in the monitor. My words were not memorable, but they were sincere.

“Thank you. Thank you,” I told him. “I have no answer to that.”

In so many ways, the end has brought me back to the beginning. The moment with Putin makes me look back on everything that’s happened since my mother came to America by boat from the tsar’s Russia. I can picture my mother. If I close my eyes, I can even hear her voice: “Again, you’re unemployed?”

She had a great sense of humor, Jenny Zeiger. The clas- sic Jewish mother. Truth is, only my mother would have be- lieved that a kid like me, who never went to college, could have had such success. The more I look back, the more un- believable it becomes. There have been so many twists and turns.

I think of my earliest memories of the Russians. As a boy I rooted for them when I studied World War II maps in the news- papers. They were fighting the Germans on the second front. Everyone I knew loved Joe Stalin. Papa Joe, we called him.

By the time I got my first teenage kiss, we hated him. Stalin had seized the Eastern bloc.

There was panic in America the year I started in radio. Sputnik had been launched. We were no longer in the lead. The Soviets could look down on us. I was a married man with a young son when I saw tanks roll down the streets of Miami dur- ing the Cuban missile crisis.

Humor helps after moments like that. The comedian Mort

Sahl did a funny bit on how things change: An American soldier gets knocked unconscious during World War II and doesn’t wake up until more than fifteen years later.

“Get me my gun!” he says. “Get me my gun! I’m gonna go kill those Germans!”

“No, no,” the doctors try to calm him, “the Germans are our friends.”

“Are you crazy?” the soldier says, “We’ve got to help the Russians get the Germans.”

“No, no, no. World War II ended years ago. The Russians are our enemies.”

“I’ll tell you what then,” the soldier says. “Get me my gun so I can help the Chinese wipe out the Japs.”

“No, no, no, no. The Japanese are now our friends. The Communist Chinese are our enemies.”

“What a crazy world.” The soldier shakes his head. “I’d better rest. I think I’ll take a vacation. Maybe a couple of weeks in Cuba.”

By the time the Vietnam War started, I was interviewing everyone from generals to Soviet defectors on local radio and television. I was Mr. Miami. We were told the war would stop the domino spread of Communism. Not long after we figured out our mistake, the Soviets made one of their own and in- vaded Afghanistan. By then, I was on all night, coast to coast. President Carter came on my Mutual Broadcasting radio show to explain the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Olympics.

I couldn’t even get CNN on my television in Washington when Ted Turner started it. Ted didn’t see the satellite as an enemy. One of the few rules he had when I joined CNN in 1985 was that we couldn’t say the word foreign. Borders were crazy to him. He wanted to use satellites to bring people together.

By the time the Berlin Wall came down, the backdrop of my show was known around the world. Mikhail Gorbachev came to meet me for lunch wearing suspenders. Boris Yeltsin watched me announce that OJ was heading down the freeway in the white Bronco. When he arrived in the U.S. for a presi- dential conference, the first question Yeltsin whispered into President Clinton’s ear was: “Did he do it?”

I think back to my mother and all those Jews who left the pogroms and Russia at the turn of the twentieth century. And I think of the irony of Putin telling me in our first meeting that his favorite place in the world to visit is Jerusalem.

How could it be that so much time has passed? Seems like I was just running down the streets of Bensonhurst with my friend Herbie to celebrate V-E Day. Suddenly, I’m celebrating my show’s twenty-fifth anniversary? Then I’m announcing that my show is going to end? When I did, the most popular sports star in Washington, D.C., was the Russian hockey player Alexander Ovechkin. And Putin called to ask if he could make a final visit before I signed off. Maybe this is what Ted Turner had hoped for when he started the network.

Yes, we have come full circle. Once again, we can be friendly with the Russians. Everything changes, and everything stays the same. Again, you’re unemployed?

Why is the world like this? I have no idea—only another good joke that confirms it.

A guy living in the Bronx takes his shoes in for repair. It’s December 6, 1941. The next day, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, and he enlists.

He goes overseas. He fights the war, meets a Japanese girl, marries her. He goes into business, lives in Tokyo for twenty-five years. One day he comes back to the United States for a busi- ness meeting. He’s going through an old wallet and finds a ticket stub for that old pair of shoes. It’s marked December 6, 1941.

He wonders if the shoe store is still there. So he asks his limo driver to take him up to the Bronx.

There it is! John’s Shoe Repair.

“I’m gonna go in with the ticket,” the guy tells the driver, “just to see what happens.”

He walks in. It’s the same repairman!

The guy hands John the repairman the ticket. John the repairman turns and shuffles to the back.

A minute later he returns to the counter and says, “They’ll be ready next Tuesday.”

From "Truth be Told" by Larry King. Copyright © 2011. Reprinted with permission of Weinstein Books.