Entering the Unknown

September, 1960

Dear Jay,

It was good to talk to you—I know things will get better because you are the kind of person who can adjust and find the good in all situations.

When I read your letter, I recalled vividly many similar times in my life. When I left home to go to Shattuck, I was truly blue. Yet I know now how fine a thing it was for me and my future. The training I received has made my life good. When I left you, Pat, and Mother to go to sea during the war, I was really shaken. I loved you and wanted to watch you and help you as you grew up—and I was leaving not knowing if I’d ever get back again. But once more, the experience and training I received more than compensated for the heartaches. Then too, I had the personal satisfaction of knowing I had done my duty.

One of the first things an education brings to people is the realization that the world is a big place—full of many different ideas and ways of doing things. You have watched our team practice and quite naturally are attuned to our ways of doing things. Bill Murray has been a fine coach for many years. Instead of wondering why they do things differently, you should be studying what they do so you will understand that their approach will get the job done more effectively—maybe more easily than we can.

When any person leaves a pleasant situation to enter the “unknown,” there is always the realization of how nice, good and comfortable things were before. Yet only by facing the future and accepting new and progressively more difficult challenges are we able to grow, develop, and avoid stagnation. You have more total, all-around ability in all fields than anyone I have ever known. You will certainly be a great man and make a great contribution to the world. But to do this you must take on new and progressively more difficult challenges. You will grow and develop in direct relationship to the way you meet and overcome what at first seem to be hard assignments. You will learn to love Duke—to take great pride in the school and their football team. You’re that kind of person. By developing as a student and an athlete, you will prepare yourself to do bigger and better things when you graduate.

Always remember that I believe in you no matter what. You must do what seems right to you. Don’t ever be swayed by what “other people will think.” My grandmother, a great lady—one of the finest I‘ve ever known—always told me when I was a young boy growing up to “dare to be a Daniel; dare to stand alone.” It is the best advice one can have for happy, successful living. After analyzing and evaluating the circumstances—always do what seems best to you in the light of your own good judgment. Only in this way can you find peace of mind because you cannot be happy doing “what other people think you should do.” You must do what you think you should do.

I didn’t quite finish this letter yesterday before practice so am doing so this morning, Saturday. Norman tied Capitol Hill last night 26–26. They miss their “Big Tiger” on defense—as well as offense.

I love you, Jay, more than anything in life. Don’t worry about things—live each day by doing your best. Will look forward to talking to you tomorrow.

Love always,Dad

When I arrived for my freshman year at Duke, I was the proverbial stranger in a strange land. The University of Oklahoma was a state-supported school located less than two miles from my home; Duke was a private institution founded in 1832 and nestled in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, about three hours west of the Atlantic Ocean.

The sons and daughters of some of the nation’s leading families attended Duke. Beginning with my senior year, 1963, the school opened its doors to racial integration. Academically, Duke is ranked today among the nation’s top institutions of higher learning. Such was the case in my day as well. A degree from Duke was and is on par with those from any of the finest schools along the East Coast.

Athletically, the Duke of my day was known for the success of both its football and basketball programs. Football coach Bill Murray won seven conference titles in the 1950s and early 1960s, including Orange Bowl and Cotton Bowl victories, and was respected as one of the finest coaches in the country. Basketball coach Vic Bubas, who arrived at Duke one year before me, quickly built the basketball program into a powerhouse, achieving an Atlantic Coast Conference tournament record of 22–6 and a Cameron Indoor Stadium record of 87–13 during the next ten years. The basketball team, now legendary under the direction of Coach Mike Krzyzewski, would later claim four national titles.

Arriving at Duke’s Wallace Wade Stadium, I was accustomed to Dad’s offensive and defensive philosophies at Oklahoma, the rhythms of his practices, and even the nature of the equipment his players used. For the first couple weeks, as I made my way from the locker room to the Duke practice field everything around me seemed all wrong. It was like turning one’s nose up at a delicious homemade cobbler simply because it was not like the ones Mom used to bake.

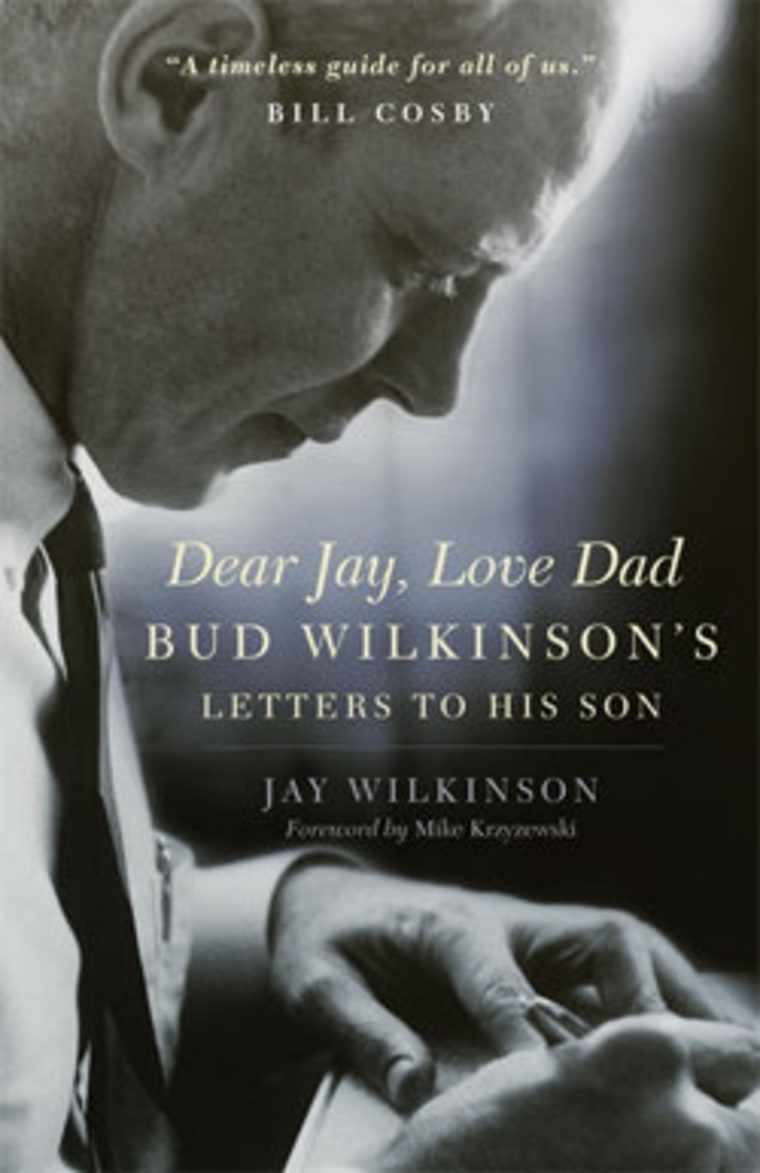

Dad’s first letter to me at school was as welcome a sight as one of Mom’s homemade desserts would have been. In the dorm room I shared with fellow freshman football player Kenny Stewart, a mountain of a young man from West Virginia, I eagerly opened the envelope and unfolded the letter, written on Dad’s University of Oklahoma head coach stationery.

My father’s character had been shaped in many ways: by family, by his time spent away from home at boarding school, by his multifaceted college experience, and by his service to country as a naval officer in World War II. His demand for excellence was sizable, both from himself and from those for whom he bore responsibility, but he never led with a whip. Encouragement and positive reinforcement defined his leadership style, and I would come to understand better, appreciate, and embrace that philosophy during my time at Duke.

In his words I held before me, Dad’s reassurance was soothing. His endorsement of Duke football coach Bill Murray was important. His faith in me was profound. I could also identify with the feelings of sadness he shared with me. It had been hard on him to leave home as a boy to attend prep school at Shattuck in Faribault, Minnesota, but it had helped to prepare him for what was to come. I knew full well about his experiences serving on the USS Enterprise in the Iwo Jima and Okinawa campaigns of World War II. He had come close to dying in a kamikaze attack on his aircraft carrier, but he had survived, unlike many with whom he served. He came through those experiences tougher and wiser, and he wanted the same kind of growth for me.

Away from home myself, I began to gain new perspective, realizing that the world was a much bigger place than I had ever imagined. I was coming to grips with the fact that life was filled with complexities, ambiguities, and at times, sadness. How people adjust and find the good in all things was an important quality and a key ingredient in maintaining happiness. When times are tough, I knew, there was a natural tendency to withdraw, surrender, and feel sorry for oneself. Dad’s focus remained upbeat and optimistic. His guidance and support helped me understand that only by accepting new and progressively more challenging circumstances are people able to develop and grow as individuals.

I began to look differently at my personal situation. My pride in and love for my new school validated both my father’s counsel and my decision to find my own way in life. I liked and respected my classmates, teammates, coaches, and professors. Most important, leaving home enabled me to acquaint myself with the fact that taking on new responsibilities was the natural order of life.

Dad’s reminder, “Always remember, I believe in you no matter what,” was a pivotal one. Encouragement and positive reinforcement are central elements in motivating others. His advocacy instilled in me a greater self-confidence, just as his teams’ successes had enabled the people of Oklahoma to see themselves in a different light.

Above all things, Dad encouraged me always to do what seemed right. Only by doing so, he said, could a person possess true peace of mind. In rereading the letter decades later, it was obvious to me that my father was preparing me for success, not only in my coming years as a football player but also in the larger scheme of my future.