If Jack Jacobs wanted a challenge, he certainly had one in 1966. He had a bachelor’s degree from Rutgers University, a wife and a daughter, and no money. He had been through ROTC, and his plan was to enter active duty to earn a regular paycheck, then attend law school when his three-year Army commitment was finished. He volunteered immediately for airborne duty—paratroopers earned extra pay for the hazardous duty.

A year later, Lieutenant Jacobs was in Vietnam as an adviser to a Vietnamese infantry battalion in the Mekong Delta. He had wanted to deploy with his unit, the 82nd Airborne Division, and when he asked the Army why he had been chosen for the frustrating job of adviser, he was told it was simply because he had a college degree.

On March 9, 1968, Jacobs was with the lead companies of his South Vietnamese battalion as they searched for the Vietcong. Suddenly, a large enemy force, hidden in bunkers only fifty yards away, opened fire with mortars, rifles, and machine guns. With no place to hide, many South Vietnamese soldiers were killed or wounded in the first few seconds.

A mortar round that landed just a few feet away sent shrapnel tearing through the top of Jacobs’s head. Most of the bones in his face were broken, and he could see out of only one eye. He tried calling in air strikes, but the intense enemy ground fire drove off the U.S. fighters. Shortly afterward, the lead company commander was badly wounded, and the South Vietnamese troops began to panic. Jacobs assessed the situation and realized that if someone didn’t act quickly, everyone would be killed. The words of Hillel, the great Jewish philosopher, jumped into his mind: “If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?”

He assumed control of the unit, ordering a withdrawal from the exposed position to a defensive perimeter. He dragged a wounded American sergeant, riddled with chest and stomach wounds, to safety, then returned to the fire-swept battlefield to rescue others. Each time he returned, he had to drive off the Vietcong, and single-handedly killed three and wounded many others. Despite being weak from blood loss, he went back time and again, bringing to safety thirteen fellow soldiers before he tried to take a brief rest—and discovered he couldn’t get up again.

During the helicopter ride to the field hospital, he lost consciousness several times. Days later at another hospital, doctors pieced his skull and face together. Though he would undergo more than a dozen surgical operations, he never regained his senses of taste and smell.

Back in the United States, Jacobs was assigned to Fort Benning, where he became the commander of an officer candidate company. About a year after the action, he received an order to report to Washington, and on October 9, 1969, at a ceremony at the White House, President Richard Nixon awarded him the Medal of Honor.

After completing graduate school at Rutgers University, where he earned an M.A. in international relations, Jacobs asked to return to Vietnam. The Army granted his request on the condition that he remain out of harm’s way. When he returned to Vietnam in July 1972, though, he immediately got himself assigned to the Vietnamese Airborne Division in the thick of fighting in Quang Tri. He walked away unscathed when the helicopter taking him to his unit was shot down, but he was subsequently wounded again. Ultimately, he retired as a colonel after twenty years on active duty—quite a bit longer than the three years he had originally planned.

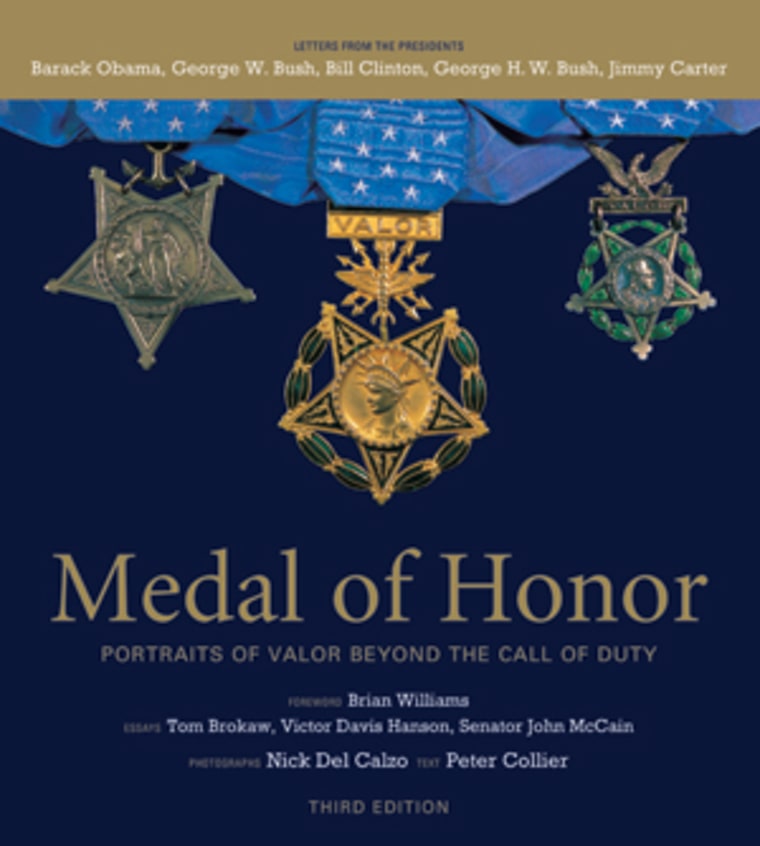

Excerpted from Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty, 3rd Edition (Artisan Books). Copyright 2011. Text by Peter Collier; Photographs by Nick Del Calzo.