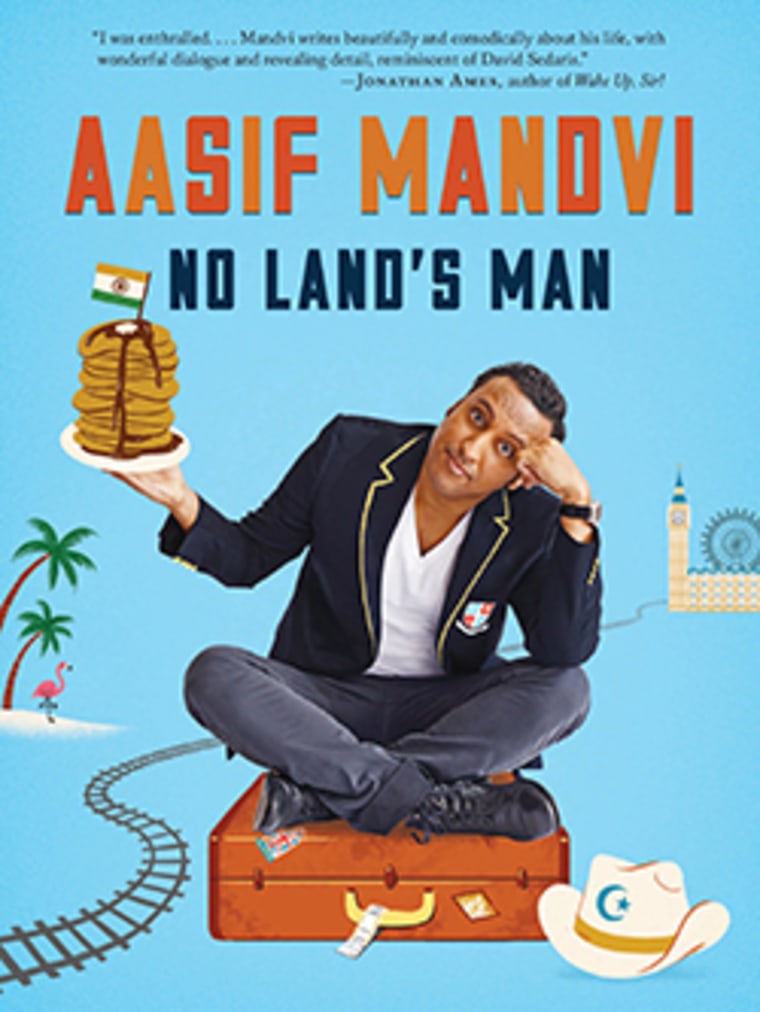

Listen to the audio excerpt HERE

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PATEL

My father moved our family to the United States because of a word. A single word that he had first overheard in conversations among returning ex-pats and in American films. It was a word whose meaning fascinated him. A word that for my father embodied the greatest part of the greatest country in the world, and by its very definition challenged other nations to do better, to expect more from themselves, to reach for the unreachable. It was a singularly American word, a “fat” word, a word that could only be spoken with decadent pride.

That word was . . . brunch!

A stack of pancakes eight inches high with five kinds of syrup: maple, caramel, chocolate, honey, and strawberry. Eggs any style. Biscuits lathered in whipped butter. Muffins, hash browns, and as much coffee as you could drink. Orange, grapefruit, and tomato juice. French toast and a side of extra crispy turkey bacon and/or sausage (because, after all, we were Muslims). All for a measly $7.95.

Brunch au Akbar!

“The beauty of America,” my father would say, “is that they have so much food, that between breakfast and lunch they have to stop and eat again. Breakfast and lunch! Put them together and you get brunch! Genius, right? Bloody Americans! I love them. Their English is atrocious, but they have a word for everything.”

In 1982, on the advice of a transatlantic real estate agent who was selling homes and businesses to adventurous Brits wanting to emigrate to the States, my father had gone on a reconnaissance mission to see if Florida inspired him enough to sell everything we owned, leave the north of England forever, and start all over again. I was sixteen and had been sold on the idea from the moment my parents first mentioned it. Compared to my stuffy all-boys private school, and my upcoming O-level exams (that I was certain would be the beginning of my academic demise within the British public school system), moving from Bradford to Florida felt akin to the day my parents finally threw out our old black-and-white TV and replaced it with color. I was willing to leave everything in my world behind—my friends, my school, and even my brand-new clock radio—to spend one day in what I imagined would be a sun-drenched beach paradise. Just as in the Hollywood movies I had grown up with, my life would be underscored by the gentle harmonies of surf rock, my girlfriend would look like Miss Teen USA, and my best friend would be a dolphin. I couldn’t wait to leave.

I remember the call he made from West Palm Beach, his excited voice on the other end of the line as he spoke to my mother, my sister, and me as we crowded around the receiver of a single rotary telephone back in Bradford.

“How is it?” my mother asked him, perhaps hoping that we could back out of this idea to once again move to a foreign land.

My parents had done this before, fifteen years earlier, leaving the steamy, spicy, colorful, shit-filled, chaotic, and familial comfort of Bombay to seek a better life halfway across the world. That time we had ended up in a snow-covered coal mining town that belched gray fumes into the gray skies of the north of England. My father, educated as a color chemist back in India, became the proprietor and sole employee of a small newspaper shop. With a portable heater below the counter warming his frozen feet during the chilly English summers, he sold cigarettes and pornography to racist gray-haired Brits who had defeated the Germans and once ruled an empire, but were now forced to watch their glorious nation be over taken by Gunga Din himself.

“It’s wonderful!” he replied. His voice was almost at the top of his register with excitement. “I just ate my first American brunch and it was delicious! The only thing I don’t like is that you can’t get a bloody cup of hot tea in this country. They drink cold tea. Iced tea! They actually put ice in their tea! Can you imagine? They also put ice cream in Coca-Cola! Bloody Americans! I love them. Their palate is atrocious, but there seems to be nothing they won’t eat.”

We all laughed, enjoying his exuberance, until my mother began to cry.

A year later we were living in Florida. We had settled in Tampa since my father, while on his reconnaissance mission, had reconnected with an old college roommate who swayed him away from West Palm Beach and convinced him that Tampa was the next great American city. Consequently, my American adventure began not on the beach, but in the suburbs.

That first summer my grandparents came from India and visited us in this land of cold tea and Coke floats. Since we were now Americans who had relatives visiting, we decided it was time to partake in the American tradition of the family road trip. We piled into a rented station wagon and headed north to see the White House and the Empire State Building.

Before we left my father had gathered us together in the living room and handed us each a white T-shirt. I unfurled mine and saw that it sported an authentic and impressive IHOP logo under which were written the words “International House of Patel.”

“But our name isn’t Patel, Dad,” I pointed out.

“Mandviwala was too expensive,” he said. “They charge by the letter. And besides, Americans don’t know the difference.”

He did make a fair point. The specifics weren’t important. What mattered to my father was that the corn-fed American IHOP manager would be so taken with these T-shirts that we would be ensured a discount if not for our brand loyalty, then hopefully for our sheer inventiveness.

We spent the next four days sitting in a cramped station wagon and sleeping in cheap motels. Whenever we got hungry, my father would make us wait, passing sign after sign for McDonald’s and Cracker Barrel until he saw what he was looking for: the steep peacock blue rooftop that signaled his brunchtime beacon. He would excitedly pull off the freeway, open the trunk, and hand us our costumes. My sister, my mother, my Indian grandparents, and I would stand dressing and undressing in the parking lot of yet another IHOP franchise in Georgia, or South Carolina, or Maryland.

My grandmother was the most uncomfortable with this ritual because the poor woman had to pull the shirt on over her salwar kameez, transforming her left shoulder into a giant mound consisting of a delicately hand-beaded chiffon dupatta stuffed under a one-size-fits-all Gap T-shirt. She looked like she had a goiter.

Once we had all donned our costumes, we would make our way across the parking lot and sheepishly enter the franchise. It wasn’t enough that this absurd spectacle was already eliciting quizzical looks and snickers from both patrons and staff, but my father had to draw further attention to it by pointing to each one of us expectantly as soon as the waitress approached our table.

“One, two, three, four, five, six,” he would say, pointing to us as we tried to hide behind our oversized IHOP menus. “Funny, right?”

He would smile and stare at the young waitress until she was finally forced to fake a laugh or look away.

If there were other Indians or Pakistanis in one of the restaurants (and there always were), they would be aghast, horrified at the sheer brazenness of our extreme frugality. They would stare in open disbelief that a man could be so insensitive as to force his wife’s aging Muslim parents to pass themselves off as Hindu so he could get free pancakes. Though some also likely wished that they had thought of the scheme themselves.

Our waitress was usually either a teenage girl or an older matronly-looking woman, wearing a real IHOP uniform, who would respond to our costumes with either a half-hearted smile, or overtly fake enthusiasm designed to garner a bigger tip.

“Oh that’s cute, did you make those?” or “Oh my goodness, that is funny. What’s a P-A-T-E-L?” or even, “Oh, wow. I didn’t know you had IHOPs in Patel. Is that where y’all are from?”

The volume of these comments was usually several octaves higher than normal. It was a pitch reserved for the hearing-impaired, the immigrant, or the obvious freeloader, of which my father may have been all three.

Then, without flinching, without embarrassment, without a hint of self-awareness or restraint or propriety, my father would invariably point to me. ME! Sixteen years old, pimple-faced, hair styled in a South-Asian Afro, a person who had no hope of having sex for at least another eight years.

“My son made them in school,” he would say. “For his grandmother . . . because as you can see, she has a deadly goiter.”

After the third or fourth time I watched this scenario play out and the poor waitress get the not-so-subtle hint to ask the manager to see if they actually offered discounts to people wearing homemade IHOP T-shirts accompanied by dying birthday grandmothers with fake goiters, I couldn’t take it anymore.

“Dad! Please!” I hissed at him across the table. “This is seriously embarrassing!”

“Embarrassing! Embarrassing?” he barked back. “This is not bloody embarrassing. You don’t know embarrassing.”

“Whatever,” I mumbled.

“Let me tell you what is really embarrassing,” he continued. “Having only one pair of shoes, that’s embarrassing. Having to study for your exams under a street lamp because you don’t have your own room, that’s embarrassing. Hanging off the side of a train on your way to work because it’s so crowded and you can’t afford a seat, that’s embarrassing.”

I could see the waitress returning from the back of the restaurant, a bemused look on her face. I really didn’t want to be there when she got to the table and explained that just this once IHOP could give my father a 10 percent discount on the meal, or whatever other paltry salve she had been authorized to apply to this overly enthusiastic customer.

“I’m not hungry, anyway,” I said and slipped out of the booth. This was a lie; I was starving. But before my father could grab my arm or catch my eye I was out the door. I decided I’d rather sit in the car during every meal than wear his stupid T-shirt ever again. For the rest of the trip my mother was forced to bring me takeout containers of lukewarm pancakes, eggs, and hash browns already growing soggy in a puddle of melted butter and syrup.

In truth, I understood my dad more than I was letting on. I knew that to my dad, America was Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory and he was a ten-year-old who had won a golden ticket. I remembered when we first arrived in Florida, my father and I would go to the grocery store produce section carrying a camera, where he would pose next to giant cantaloupes and engorged honeydews. He took smiling pictures of his family surrounded by gastronomical excesses: giant bottles of cherry Coke, humongous jars of peanut butter, and industrial-sized cereal boxes that could feed an Indian family of ten. He would then send these photographs back to my aunt in India, who for many years afterward believed that Albertson’s and Safeway weren’t mere food stores but fantastical American theme parks.

Whenever there was an offer to buy one and get the other for half price, my father was the first in line. His ability to consume knew no bounds and there was not a promotion or an advertisement that did not interest him. He embraced America and its consumer culture with open arms and an even wider mouth.

While my father loved excess, I dreaded his impromptu gastronomical field trips. Even before the IHOP debacle, I distinctly remember a fight we had at our local Baskin Robbins. His favorite flavor was something like Chocolate Pecan Fudge Butter Nutter with extra sprinkles and M&M’s. When I ordered plain old chocolate he took it as an insult.

“They have thirty-two flavors, thirty-two bloody flavors,” he said, “and you order chocolate? Chocolate you can get anywhere in the world. Why did we come to America? It is an insult to every beggar on the streets of India to simply order chocolate. We didn’t sacrifice everything and come to the land of plenty so that you could be satisfied with bloody plain old chocolate ice cream. Now order like an American. Two scoops, different flavors, extra toppings on a sugar cone.”

Things got even worse a few weeks after our road trip when my father decided to break the tense silence that had festered between us by insisting that I accompany him to get pizza. After ordering two large pies (because the second was half-price), he asked me what I wanted to drink.

“I just want a medium soda,” I said.

“Get the large,” he said.

“I don’t want it.”

“You get the Extra Large Gulp for only thirty-nine cents more.”

“No, I just want the medium.”

“It is only thirty-nine cents more and you get twice as much. We will take the large one.”

“I don’t want it.”

“Damn it, son!” he yelled.

His voice was starting to attract the attention of the other customers in line. I could feel the back of my neck getting flushed with embarrassment.

“When will you become an American?” he continued. “Okay, pour the extra thirty-nine cents-worth into a cup and I will drink it later.”

I turned on him, furious. “See? You’re doing it again. You just can’t help yourself, can you?”

“What happened? What did I do? It’s only thirty-nine cents more,” he said. “What is wrong with you?”

“What’s wrong with me?” I laughed. “What is wrong with you? When will you become an American? An American who lives in the land of plenty but knows how to practice a little moderation and restraint. Someone who doesn’t have so little dignity that they are willing to siphon off a half-liter of soda just to take advantage of a stupid thirty-nine cents saving?”

My father looked at me without saying a word. His face was expressionless for a moment and then slowly he began to smile.

“You think Americans practice moderation and restraint?” he asked.

“Umm . . . yeah,” I nodded, knowing I might have made a strategic error in saying so.

“Are you a bloody idiot?” he asked, his usually high-pitched voice now dropping an octave, giving gravitas to what he was about to tell me.

“Son, this is a country where you can walk into a grocery store and purchase a ‘turducken.’ Have you ever heard of a turducken?”

I shook my head.

“A turducken is a turkey that is stuffed with a duck that is stuffed with a chicken that is stuffed with a sausage. No one except an American would think of eating such a thing. I have never sent a picture of one to your aunt because I am afraid if she knows something like that exists, she will kill herself. Do you get my point?”

His face was deadly serious. I did get it.

“And as far as dignity goes,” he continued, “no one had more dignity than your grandfather, a man who woke up every day and could only afford chai and bread for breakfast, and yet he dressed in a clean starched white shirt and held on to his briefcase and stood with dignity as he hung on to the side of a train on his way to work.”

I stared at the ground for a moment collecting my thoughts. I had been schooled.

Then he put his hand on the back of my shoulder.

“How about we forget the pizza? Instead, in your grandfather’s name, let’s go eat a ridiculously large brunch.”

From No Land’ Man by Aasif Mandvi, published by Chronicle Books