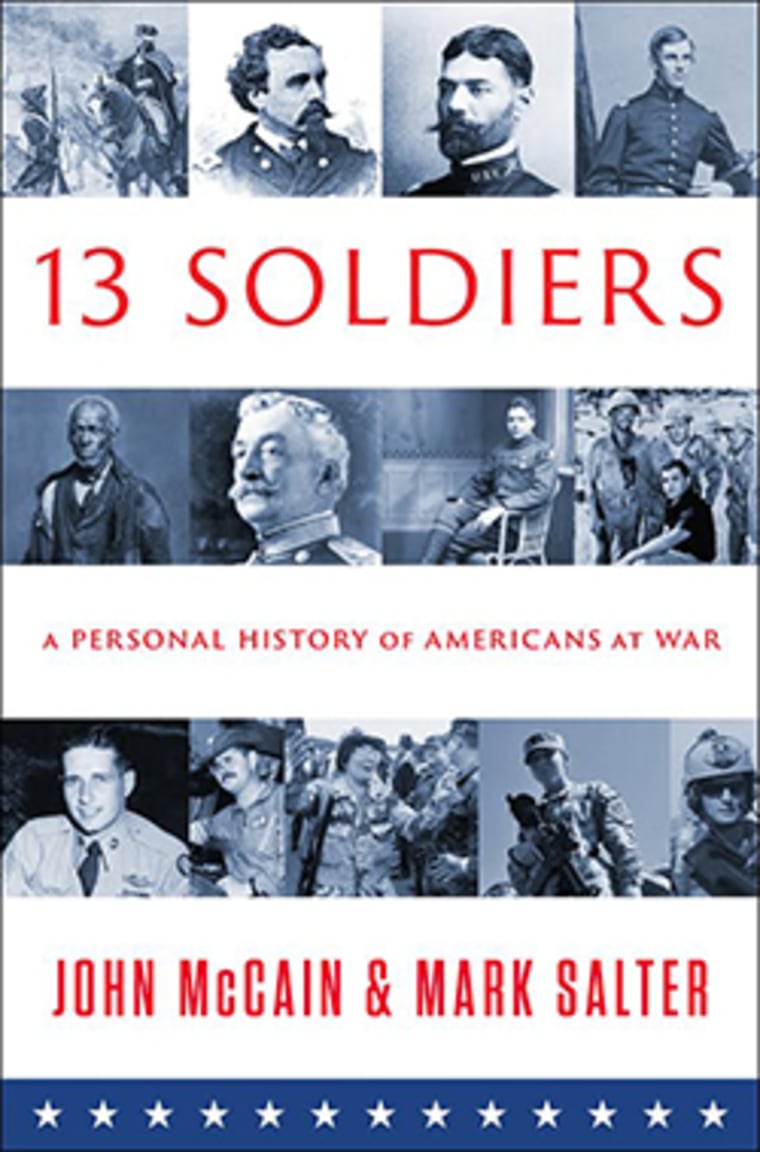

Chapter One

Soldier of the Revolution

Joseph Plumb Martin, who joined the Revolutionary War at 15 and fought from Long Island to Yorktown

Two days after John Hancock affixed his extravagant signature to the Declaration of Independence, an intelligent, spirited boy of fifteen pretended to write his name on an order for a six-month enlistment in the Connecticut militia.

“I took up the pen, loaded it with the fatal charge, made several mimic imitations of writing my name but took especial care not to touch the paper . . .”

Someone standing behind him, probably a recruiting officer, reached over his shoulder and forced his hand. The pen scratched the paper. The helpful agent declared, “the boy has made his mark.”

“Well, thought I, I may as well go through with the business now as not. So I wrote my name fairly upon the indentures. And now I was a soldier, in name at least, if not in practice.”

Joseph Plumb Martin would remain a soldier for the duration of the revolution. He first saw action as part of Washington’s outnumbered army on Long Island. Five years and many hardships later he witnessed the British surrender at Yorktown. He lived the remainder of his life in obscurity and poverty. He received little compensation for his service, not even, at least in his lifetime, the reverence of his countrymen that was his due as one of the patriots to whom they owed their liberty.

George Washington’s self-control, maintained in its severest trials by a supreme exertion of will, seldom failed conspicuously. But in the instances when it did, the effect was spectacular. Those who witnessed Washington’s lost temper were stunned by its ferocity, and left accounts of the experience that imagination need hardly embellish.

Around noon on September 15, 1776, after galloping the four miles from his command post at Harlem Heights, Washington beheld five hundred or so shell-shocked Connecticut militia fleeing from hastily constructed defensive works on the East River at Kip’s Bay. As they ran from British and Hessian bayonets, he urged them to turn and retake the ground they had surrendered without a fight. They flooded past him.

Washington’s physical bearing appeared no less striking, perhaps more so, for his loss of composure. He wheeled his white charger amid the noise and confusion, his powerful legs gripped the animal firmly, his broad shouldered, 6-2 frame sat erect in the saddle. Enraged, he cursed and threatened officers and men alike. He struck at a few with his riding crop. He drew his sword and pistol. He charged toward the enemy within range of their muskets, seeking to impart his courage by his example.

All to no avail as the terrified farmers and shopkeepers, boys and men, some having lost or abandoned their muskets, others armed only with pikes, found more to fear from the glittering bayonets of the enemy than the violent anger of their Commander-in-Chief. He threw his hat to the ground, and groaned, “Are these the men with which I am to defend America?” At last, the great man’s frantic aides convinced him to ride to safety.

Private Joseph Martin must have made his escape that day by a route that avoided proximity to the raging Washington. Had he witnessed the unforgettable sight, he would surely have recounted it in his remarkable memoir, which includes a characteristically candid and ironic account of “the famous Kip’s Bay affair, which has been criticized so much by the historians of the Revolution.”

The British Commander-in-Chief, General William Howe, had waited more than two weeks to pursue the rebel army after Washington ordered its evacuation from Long Island to Manhattan on August 29. In the interim, Washington and his officers had decided to abandon New York City, recognizing it was indefensible while the British fleet commanded its rivers and harbor. The American forces were widely scattered. Four thousand men under General Israel Putnam garrisoned the city in lower Manhattan. Nine thousand men under William Heath protected the army’s escape route in the north from Harlem to Westchester County. Dispersed widely across the center of Manhattan were Nathanael Greene’s several thousand men, including the Connecticut militia under the command of the experienced Colonel William Douglas.

Washington was unsure where the British invasion would make landfall. He feared they would try to block his outnumbered army’s escape by attacking at Harlem, where he made his headquarters and where his largest force was deployed. On September 13, four large warships (by Martin’s account although most historical accounts put the number at five), sailed into Kip’s Bay, a small cove that offered a deep water anchorage on the East River’s east bank.

Half of Martin’s regiment was deployed to Kip’s Bay that night to, in his words, “man something that were called ‘lines,’ although they were nothing more than a ditch dug along the bank of the river with the dirt thrown out toward the water.” They returned to camp in the morning, and the following night, the other half of the regiment, including Private Martin, were ordered to take their place in the lines. Sentinels were posted along the river for several miles, and passed the watchword, “all is well,” on the half hour. “We will alter your tune before tomorrow night,” Martin remembered the British on their warships retorting. “They were as good as their word for once.”

He awoke that Sunday morning tired—and, as he would be throughout most of the war, starving—to see the warships anchored within musket range of his regiment’s crude defensive line. Although the ships’ crews appeared to be busy with preparations nothing happened until mid morning. “We lay very quiet in our ditch waiting their motions,” he recalled. By10:00, he could see scores of flatboats embark from Newton’s Creek on the Long Island shore, ferrying four thousand British and Hessian soldiers across the river. They formed their boats into a line and continued “to augment their forces … until they appeared like a large clover field in full bloom.” By late afternoon another nine thousand would join them.

Martin was idly investigating an old warehouse near their lines when, at 11:00, he heard the first roar of ships’ cannon, which, by his account, constituted over a hundred guns. He dove into the ditch and “lay as still as I possibly could” until British guns leveled the militia’s breastworks, burying men in blasted earth. At that point, realizing they were completely exposed to enemy fire, their officers neither possessing nor issuing orders to continue their futile resistance, to the dismay of their Commander-in-Chief, the Connecticut men ran for their lives.

“In retreating we had to cross a level clear spot of ground 40 or 50 rods wide,” Martin wrote, “exposed to the whole of the enemy’s fire; and they gave it to us in prime order. The grapeshot and langrange flew merrily, which served to quicken our motions.”