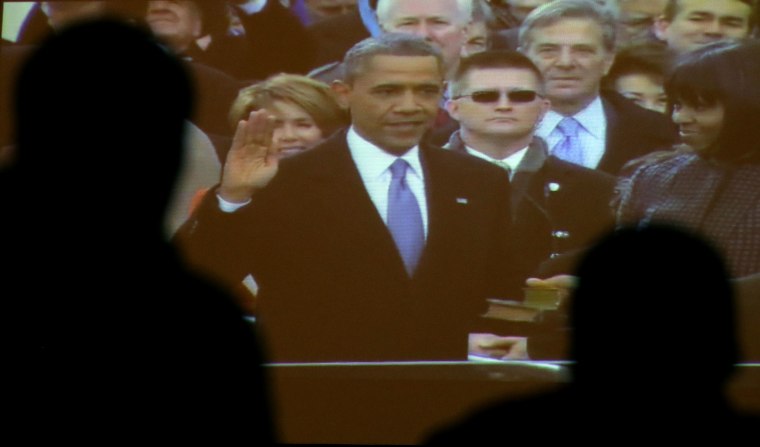

There was a moment during the inauguration when my attention shifted from the spectacle of a president being sworn in, his elegant wife holding the bible as he took the oath of office to something far less notable. The National Mall was filled with citizens who had come from across the country to witness this ritual, but those aerial shots from above the mall also revealed crowds notably smaller than they were four years ago. The truth, as always, is in the numbers.

Despite relatively warm weather and signs that the nation is slowly emerging from its economic doldrums the number of attendees today was only about a third as large as the throng that braved arctic temperatures to witness the 2009 inauguration. The cynical perspective would see those numbers as a barometer for the president’s falling appeal, a reflection of his diminished electoral standing or feeble mandate. But I saw those smaller crowds as a signpost of progress: we’ve reached a point where a black presidency is normal enough that large numbers of us can blow off his inauguration.

This time four years ago I arrived on the national mall at 5 a.m. I huddled against the cold with complete strangers for seven hours for a single reason: to be able to tell my grandchildren I saw the first black president sworn in. Today, after giving serious consideration to a last-minute trip to the nation’s capital, I watched it on television. That decision conjured memories of my parents telling me about the era when they would rush home any time there was an African American on television. Nat King Cole’s short-lived variety show was required viewing not simply because he was a talented entertainer but because a black entertainer on TV represented a kind of success by proxy for all of us.

President Obama’s legacy is inescapably tied to the history of race in this country. A century from now discussions of his presidency will likely still be prefaced by the words "first black." Race has long been the axis around which a good deal of our national history revolves. But if anything, the diminished numbers on the mall suggest that we have the capacity to think of him beyond those terms.

Were this fiction, the inauguration of a black president on the day we officially celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day would seem too heavy-handed to be credible. Yet it is significant in ways we have yet to consider. Throughout the 2008 race black support for Obama was frequently dismissed as simple racial allegiance while white support was commonly maligned as liberal guilt or an attempt to purchase absolution for racism at the ballot box. The story was never that simple: “racial allegiance” failed to generate much black support for Al Sharpton, Alan Keyes, Shirley Chisholm or other black presidential candidacies. And during his historic 1984 presidential campaign Jesse Jackson failed to garner the endorsements of black leadership--even many of those who'd fought in the trenches of the civil rights movement with him. Few considered that the content of Obama’s character was far more important than the color of his skin for black voters during the 2008 election.

During the 2012 election, strategists suspected that the novelty of electing a black voter had worn off and we could expect diminished turnout across the board but especially among black voters. Yet we saw record turnout in communities of color on Election Day.That fewer of those people made the trip to Washington D.C. suggests they were thinking about their interests, not symbolism, in the voting booth. In the next four years those voters will expect their president to address immigration, climate change, the lagging recovery among blacks and Latinos and the menace of gun violence in our cities. The fact that he’s black will not exactly be an afterthought but it will matter far less than his actual accomplishments.

Symbolism fades; accomplishments endure. That might not have been the change most of us anticipated four years ago but it could well be the most important.

Jelani Cobb is author of The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress. For more on the president and race, see the discussion below from Sunday's Melissa Harris-Perry.