If the Supreme Court strikes down a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act this year, it will largely come as the result of events that began in Shelby County, Alabama, where a disputed city council election has thrown into doubt the future of a landmark law that stops state and local governments from making it hard for minorities to vote.

Long-time Shelby County resident Frank Ellis is the attorney who brought the suit, which the Supreme Court will hear Wednesday. In his argument:

"The South has changed, it is not the same as it was in 1964...The whole country has changed, we are a dynamic society, not just in Alabama, but everywhere."

Indeed, one need look no further than the results of the most recent national elections for evidence of just how "dynamic" a society this is. For some reason, Chief Justice Roberts decided only a few days after the president's re-election to revisit an issue he had ducked just three years earlier in a case which bears the imposing title, "Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No.1 vs. Holder."

Writing for a majority of eight-to-one, Roberts sounds a bit like Mr. Ellis of Shelby County. According to the New York Times, Roberts said that "the historic accomplishments of the Voting Rights Act are undeniable." But these days, he went on, "things have changed in the South." Roberts further wrote that the 16 jurisdictions subject to Section 5 of the law were selected on the basis of information dating back as far as 1964, and whether they blocked access to the ballot-box with devices, such as literacy tests, which have long since vanished.

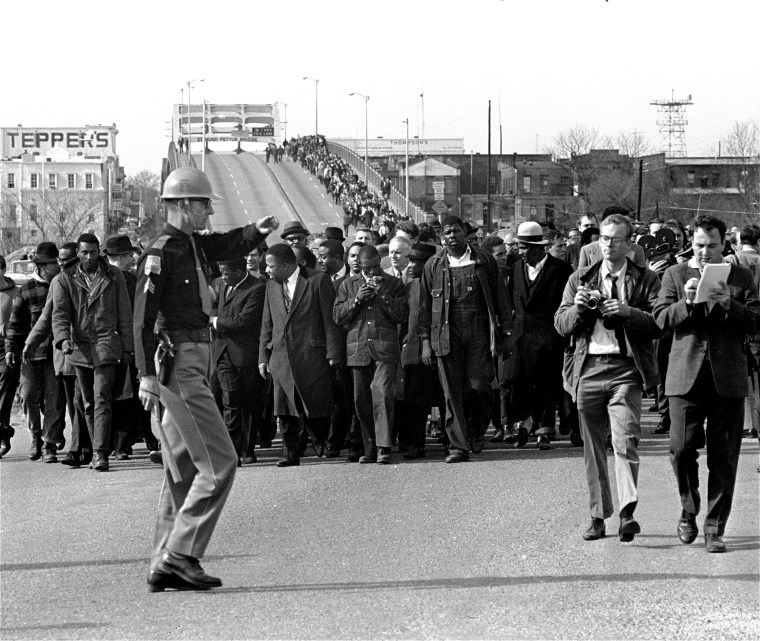

It was not always thus, of course. In 1966, when it upheld the Voting Rights Act, the high court wrote that the law was a "response to an insidious and pervasive evil which had been perpetuated in certain parts of our country through unremitting and ingenious defiance of the constitution." It was entirely appropriate, the justices continued, for Congress to "limit its attention to the geographic areas where immediate action seemed necessary." Although Chief Justice Roberts and others may think that Section 5 is outdated, courts relied on that provision to block voter identification requirements in Texas and cut-backs to early voting in Florida during the last presidential election.

Will Section 5 still be there when the nation votes again in 2016? Martin talks to Jonathan Capehart of the Washington Post and Maria Teresa Kumar, president of Voto Latino, for more insight: