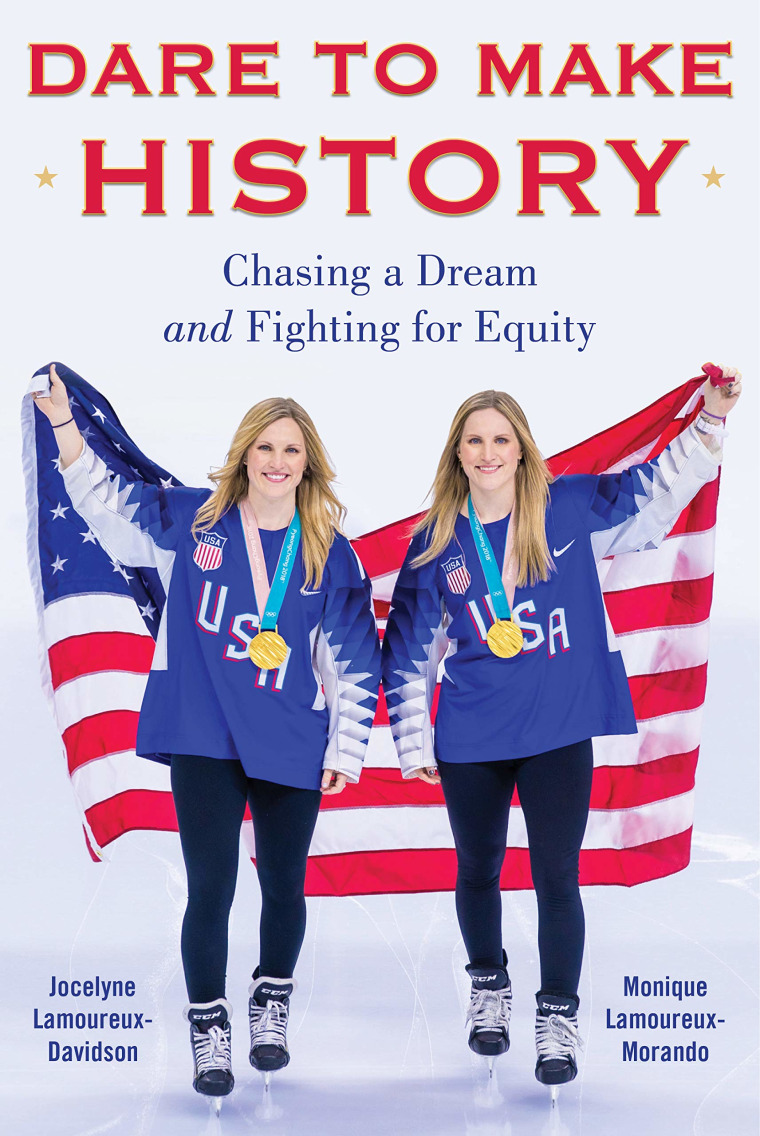

The following is an excerpt from "Dare to Make History: Chasing a Dream and Fighting for Equity," a new book by Olympic hockey gold medalists and Know Your Value contributors Monique Lamoureux-Morando and Jocelyne Lamoureux-Davidson:

JOCELYNE:

September 2019. About a week after our first camp since our gold-medal win in South Korea, we were at home when we received word that both of us had made the roster for the 2019 Four Nations Cup. Although we hadn’t played in a game for more than eighteen months, we had showed up at camp close enough to Olympic form and demonstrated that we still had the right moves, muscle, and motivation to compete at an elite level. We had proved that we could be mothers and still make an elite U.S. Women’s National Team. Mission accomplished, and point made.

Working toward the creation of a true professional hockey league for women was the next important step in our battle for gender equity in hockey. Reminiscent of our 2017 negotiations with USA Hockey, one hundred and seventy of the best players in the world banded together and formed the PWHPA. We immediately pledged that none of us would play in an existing professional hockey league in the 2019–20 season as we worked toward the creation of a bona fide professional league, which we believe needs to be under the auspices of the National Hockey League.

For women’s hockey to reach its full potential, we need the same continuum of opportunities in hockey that the men have—from youth hockey to high school and college hockey to the national team and the Olympics, and ultimately professional hockey to provide opportunities to play in between Olympic cycles and for the dozens of elite women players who will not make the national team.

In 2020, with the help of Billie Jean King and Illana Kloss, the players organized and executed an amazing exhibition tour, which we dubbed the Dream Gap Tour. The tour brought the best players in the world to six cities in Canada and the United States, which hosted a total of twenty-four games as well as a series of hockey clinics and other appearances.

During the course of the tour, we saw hundreds of young girls showing up and waving signs of support and thanking us for our leadership. Girls lined up for autograph sessions and hockey tips. The warm and enthusiastic embrace was just like the aftermath of our negotiations with USA Hockey and winning Olympic gold. We believe we are demonstrating again the appeal of women’s hockey.

At thirty years old, age was on our minds. Not that we were old—or felt it. But every athlete has a finite competitive lifespan, and the national team roster was filled with players at least five to ten years younger than us. Like Monique and me a decade ago, they were climbing the ladder up the ranks, looking to carve out a place for themselves, and ultimately play in the 2022 Olympics in Beijing. Many of them had grown up watching us play. We relished the opportunity to serve as examples the way players like Angela Ruggerio had done for us—and also as links between generations who fought on the ice and battled just as hard off it for the betterment of our sport.

If the time ever came when they had to face the same challenges that con- fronted us, we wanted them to feel a connection to the past and use it to find the courage to do the right thing for themselves, for the team, and for future generations of female hockey players.

MONIQUE:

We continued to train full time— five days a week at the gym, skating at the Ralph in the early mornings. We attended three more USA Hockey camps. And we reveled in the continued growth of Mickey and Nelson. They seemed to get bigger every day—and were developing real personalities. Watching them grow up filled our hearts with love—and grounded us as to what was really important in our lives.

In January 2020, we participated in three of the five games in the US-Canada Rivalry Series, created by USA Hockey and Hockey Canada to provide more highly competitive games in between the Olympics and World Championships. The games were hard-fought and fun. The US won the first two, although we were not on the roster for those games. We had been sent home after a five-day camp, along with twenty other players. This was the first major roadblock we had faced in a while as hockey players, and contributed to our developing thought process as to our priorities going forward.

We were back for the final three games of the series. True to form in any US-Canada series, Canada stormed back to win Game 3 in overtime by a score of 3–2 in Victoria, British Columbia, and then we won the fourth game of the series in Vancouver by a score of 3–1. The final game of the Rivalry Series was in Anaheim, California, where we played in front of the largest crowd ever to see a women’s hockey game in the US. I scored the tying goal to send us into overtime, and we eventually pulled out a 4–3 victory to take the series.

But the real win for those of us who had been around a while was looking up into the stands and seeing young girls, their moms, and even some of their dads wearing USA jerseys and holding up signs that said, “We love you,” “You’re our heroes,” and “Thank you, USA.” At intermission, the ice filled with little girls ten and under who came out in their hockey gear and played shortened games. The cool part was that only a few years earlier, our teammate Annie Pankowski had been one of them. The sport was growing for a reason. The game in Anaheim came at the end of a really tough couple of weeks. This was the longest we had been away from the boys since their birth. We thought we had done a good job balancing our roles as mothers and as elite hockey players, but those twelve days were really tough on us. In fact, if there is anything beyond “really tough,” that’s what it was like. Bottom line: we were pretty miserable.

We also had to interrupt camp to fly to Edmonton for our grandmother’s funeral. She had passed on the day we left for camp. It really wasn’t a close call—and the coaches said they understood. It wasn’t ideal to leave, but we had our priorities, and family was always top of mind. Our grandmother had always prioritized us—we needed to be at her funeral with the rest of our family. So after our game in Vancouver, we flew out Thursday morning to be with family in Edmonton. The funeral was on Friday, and we woke up at 5 a.m. on Saturday to go to the airport and made it to Anaheim in time for the pregame meal and to play in the final game at 7 p.m.

The challenges of this camp caused us to accelerate a tough, critical look at what we were doing, which had been percolating for several weeks. People always ask us how we think we did in camp, and this time, answering honestly, we couldn’t say that we crushed it. We were proud of how far we had come— proud that we had battled back to elite physical shape after giving birth—proud that we were competitive with the best women’s hockey players in the world, even if we weren’t totally back in Olympic shape. We felt like we still had a lot of hockey left in us. But were our hearts and minds as committed? As our dad had taught us so long ago, we needed to carefully assess our priorities.

As we did that, we looked at our new coaches and wondered how committed they were to us. It was pretty clear that they were making at least tentative decisions—and that those decisions were not putting us in a position to be fully competitive. The coaches weren’t very familiar with us as players or as people, and based on our limited playing time, we could see they were more interested in giving quality minutes to new, younger players, who reminded us of ourselves when we were first trying to compete for a national team slot. While there was a part of us that wondered whether we were being given a true, fair shot to come back after our maternity leave, that might have been unfair.

JOCELYNE:

Following this twelve-day camp, we received the disappointing, but not very surprising, news that we had not made the cut for the national team for the 2020 World Championships. (As it turns out, the 2020 World Championships were canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.) We had missed national teams before, but that was when we were eighteen, with a huge future and coaches asking us to be patient. This was different. Our coaches told us that we would be invited to attend the next USA Hockey camp, in August, but they also warned us that there was a group of younger players that they wanted to look at and that making the team would be an uphill climb.

For the first time, we thought about whether we wanted to control our own exit strategy—and not leave it up to a group of coaches who really didn’t know us that well on and off the ice. We still loved hockey—and we thought we could compete on an international elite level if we were given a full and fair opportunity. And there was a big part of us that believed that if we put our hearts fully into it, we could overcome the coaches’ skepticism and make the next team. We had turned around coaches’ skepticism before, including our coaches for the 2018 Winter Olympics, where we won gold.

But we also loved the rest of our lives, which were richer with opportunities than we ever imagined would be the case. First and foremost, we had our boys, and we now knew that nothing in our lives would ever be more import- ant than Mickey and Nelson—until we had other children, which was also something that was increasingly on our radar screen. We knew that the tough twelve-day trip was the first of many tough twelve-day hockey trips to come, and it was hard to process that.

Our ongoing work with our teammates for the future of the sport was also really important to us. So was our work to pursue a real professional hockey league for women in North America. And we were looking at upcoming negotiations with USA Hockey to make sure that we held onto our hard-fought gains from 2017—and maybe expand on them.

We thought back to our musings as young hockey players in our teens and twenties that being Olympians, winning an Olympic medal, and winning an Olympic gold medal were important not just for the hardware, but for the platform that being Olympians would give us to advocate for causes that we cared about. Through our appearances and partnership with Comcast, we had gained much more insight into how to use our visibility as Olympic gold medalists to be difference makers for the future.

We were also passionate about activating our foundation and seeing how much change and impact we could create in North Dakota. And we knew we wanted to continue to advocate for gender equity, closing the digital divide, racial justice, and other issues that could help level the playing field for under- represented populations around the country.

As we began to reflect on our future, we realized that, over our careers, we have achieved all of our hockey dreams. Winning three national champion- ships at Shattuck. Check. Helping to turn around the women’s hockey pro- gram at our hometown university, the University of North Dakota. Check. Making countless national teams—and winning twenty international medals between us. Check. Playing in three Olympics—together. Check. And winning two silver medals and one gold medal in those three Olympics. Check. Proving we could work ourselves back into Olympic shape and make a national team after giving birth. Check.

As our dad told us back in high school, sometimes you have to make choices in your life. When we were in college, we chose hockey and academics over our social lives. We are blessed today to have at least three fantastic choices—our young sons and families, our community engagement, and hockey. In the end, ordering our priorities is actually pretty easy. We choose Nelson, Mickey, and our families, and our community commitments, including our work to fight for gender equity, to advance the sport of women’s hockey, and the work of our own foundation.

MONIQUE AND JOCELYNE:

While none of these types of life choices is easy, we are comfortable with and proud of our legacy. The individual games will likely fade from memories (maybe except the gold-medal game in Pyeongchang). Our medals will be mentioned (we will always be Olympic gold medalists). But the changes we have brought to women’s hockey and the opportunities we have created for girls to dream big, just as we did, will have a lasting impact. They will go down in history. And we will be remembered for the difference we made in our sport—and for changes we have helped bring to underserved communities around the country—and the difference we will continue to fight for in the years ahead.

Our struggle for fairness and equity for women and girls—in hockey and in life—and for anyone or any group that is being left behind—has not ended. It goes on. We’re not skating off into the sunset until we know that the many girls we hear from through social media, email, in arenas where we play hockey, and old-fashioned letters get equal treatment with their male friends. We’re not unlacing our skates until we know that maternity-leave policies in the United States match those available essentially everywhere else in the world. We’re not taking off our gloves until pay equity for women and people of color is a reality in this country instead of an embarrassment. And we’re not laying down our sticks until the digital divide is closed in this country.

Join us! Even if you can’t skate, we want you on our team. Despite all of the challenges, or perhaps because of them, life can be truly amazing. You have to set goals, work hard, embrace the adversity that will undoubtedly come your way, be a great teammate, know that the hockey gods are watching, and dare yourself to make history.

That’s what we did.