As a legal scholar who once campaigned against the Bush administration’s human rights abuses, President Obama surely knows the international rules on the treatment of prisoners. If so, he didn't let on during his press conference this week. When a reporter questioned the administration’s use of forced feeding to put down the current hunger strike at Guantanamo Bay, the president had only seven words to offer: “I don’t want these individuals to die.”

A noble intention, to be sure, but his response skirted an issue that warrants closer scrutiny. Force-feeding prisoners violates longstanding international conventions. Medical societies, legal societies, international relief organizations and United Nations officials are all calling on the Pentagon to stop the practice, and some human rights advocates are demanding sanctions against health professionals who take part. But beyond the president’s cryptic reply, the administration has yet to explain its reasoning.

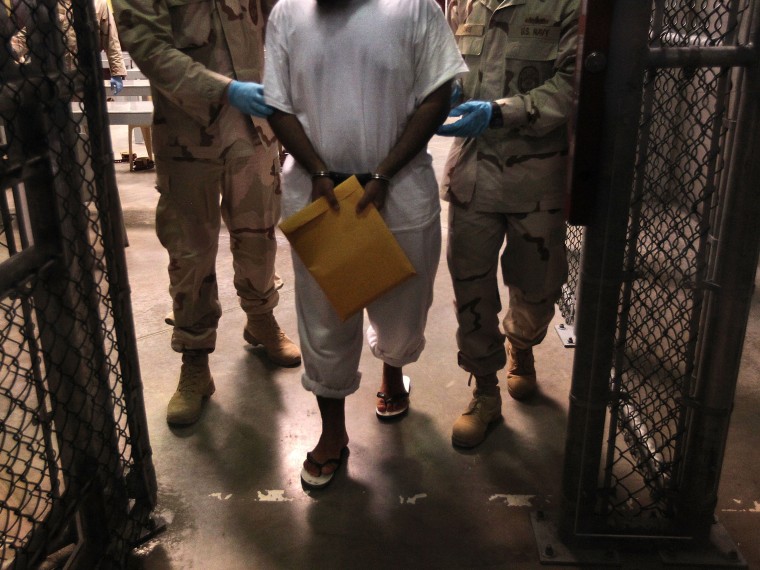

Obama didn’t create this mess. He came to office promising to close the prison camp, but Congress blocked every exit. More than four years later, 166 prisoners still languish there. Many were swept up by U.S. forces in the aftermath of 9/11 and the early days of the Iraq war and have been held without charges ever since. Several have died violently during their detention. Others have attempted suicide in what their lawyers describe as a “pit of hopelessness.” As the president said this week, “The notion that we’re going to keep over a hundred individuals in a no man’s land in perpetuity is contrary to who we are, it is contrary to our interests, and it needs to stop.”

But while the administration struggles to re-engage Congress, the prisoners’ despair is becoming a humanitarian emergency. Over the past three months, 100 of the 166 detainees have joined a hunger strike to protest their harsh confinement and the lack of legal recourse. Instead of trying to address their grievances, the Pentagon has flown 40 medics to Guantanamo to nourish them by force. On April 30, The New York Times reported that the Pentagon had “approved” 21 of the hunger strikers for “enteral feeding.”

That procedure, which the Bush administration used repeatedly to quash Guantanamo hunger strikes, is excruciating even when performed on a willing patient. “Some patients may scream and gasp as the tube is introduced,” New York City physician Kent Sepkowitz wrote in a Daily Beast essay this week. “The tear ducts well up and overflow; the urge to sneeze or cough or vomit is often uncontrollable. A paper cup of water with a bent straw is placed before the frantic and miserable patient and all present implore him to Sip! Sip! in hopes of facilitating tube passage past the glottis and into the esophagus and stomach.”

“The procedure is, in a word, barbaric,” Sepkowitz writes. “And that’s when we are trying to be nice.”

By forcibly intubating a resistant prisoner, military officials can easily pump liquid calories into his digestive system. But it’s a delicate procedure when performed on someone who has been fasting. As Boston University physicians explained in a 2007 JAMA article on forced feeding, the sudden replenishment can cause hyperglycemia, severe fluid retention and a dangerous depletion of phosphate in the blood—a cluster of symptoms known as refeeding syndrome. “Repeated insertions of the feeding tube . . . also can lead to mechanical complications,” the experts wrote, “such as . . . nasopharyngeal or esophageal trauma and, rarely, esophageal perforation.”

Many medical treatments are harsh, demeaning and risky. That’s why physicians around the world vow never to perform them on a competent patient who declines. The 1948 Geneva conventions explicitly prohibit the “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment” of prisoners—and medical authorities have repeatedly affirmed that forced feeding crosses that line. “Forcible feeding is never ethically acceptable,” the World Medical Association states in its most recent (2006) declaration on the issue. “Even if intended to benefit, feeding accompanied by threats, coercion, force or use of physical restraints is a form of inhuman and degrading treatment.”

Over the past week, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the United Nations human rights office, the American Medical Association, and a broad coalition of legal, medical and religious societies have all affirmed that judgment, calling on the administration to address the Guantanamo prisoners’ desperation without flouting medical ethics or international law. “The forced feeding of detainees violates core ethical values of the medical profession,” AMA president Jeremy Lazarus writes in an April 25 letter to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel. “Every competent patient has the right to refuse medical intervention, including life-sustaining interventions.”

How does the administration respond to all of this? Has the Pentagon decided that international law actually permits the forced feeding of competent prisoners? Has it found the hunger strikers incompetent to voluntarily refuse treatment? Or is it consciously defying global conventions because it disagrees with them? The White House didn’t respond Friday to a request for clarification.

Policymakers are not the only ones with serious questions to address. Medical professionals are ethically bound to honor patients’ rights, even if it means defying government orders. Dr. Steven Miles of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Bioethics notes that physicians in eight countries have been disciplined or prosecuted since the 1970s for abetting official human rights abuses.

One of the first was Dr. Benjamin Tucker, a South African physician who was barred from the profession for his role in the mistreatment of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. “There are strong parallels between the Biko case and the ongoing role of US military doctors in Guantanamo Bay and the War on Terror,” Miles and 265 other physicians wrote in a 2007 letter published in the Lancet. “[But] no health care worker in the War on Terror has been charged or convicted of any significant offense despite numerous instances documented . . . The attitude of the US medical establishment appears to be one of “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.’”

With its open letter to the Pentagon, the AMA has shown that it dares to speak out. Will the group match words with deeds, by censuring doctors who “violate core ethical values of the medical profession"? Like the White House, the AMA went silent when msnbc posed that question on Friday. But the question isn’t going away.