There's no denying the importance of the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. They're the first two nominating contests; their results help narrow presidential fields; and these states help set a direction for the broader fight that other states follow.

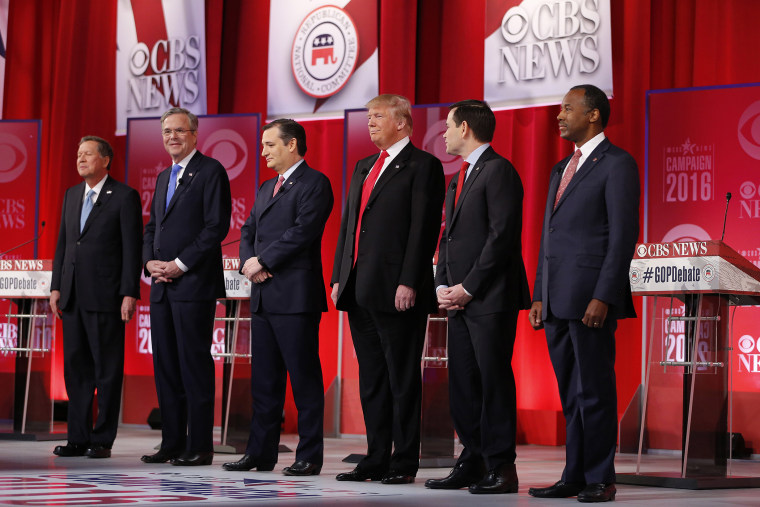

But it's possible to do well in Iowa and New Hampshire, even without winning. Presidential nominating contests, after all, are about earning delegates, not votes. In Iowa, Ted Cruz won the Republican contest, but nine candidates ended up winning at least one delegate. In New Hampshire, Donald Trump easily prevailed, but five candidates ended up with at least three delegates.

Saturday's Republican primary in South Carolina, however, is a different kind of contest. The

Washington Post had

a good piece on this yesterday.

By Saturday night, after polls close in South Carolina, Donald Trump is poised to have a gigantic lead in the Republican delegate race. By no means an insurmountable one, of course, but a big Trump victory there will start to raise questions about where, if anywhere, he can be stopped. Unlike Iowa and New Hampshire, delegates in South Carolina are allocated by a modified winner-take-all system. If Trump wins South Carolina -- which a new CNN/ORC poll suggests he's still well-positioned to do -- he gets 29 delegates, without qualifications. That's only slightly fewer than all of his competitors have to date, combined.

A total of 50 delegates are available in South Carolina: 29 to the winner of the primary, and then three delegates for each of state's seven congressional districts. Mathematically, it's almost impossible to win the primary without winning a few of the district, so it's safe to say Saturday's winner will end up with somewhere between 38 and 50 delegates, just from this one contest.

And that would pack a significant electoral punch: Iowa and New Hampshire combined offered the candidates about 50 delegates.

The conventional wisdom says Trump is favored in South Carolina, with a close contest between Marco Rubio, who enjoys the enthusiastic support of the state GOP establishment, and Ted Cruz for second place. While that fight is no doubt interesting, let's be clear about the practical implications: finishing first in this primary is about winning delegates; finishing second is about media hype and bragging rights.

And looking ahead to two weeks from now, the

New York Times reports that the delegate math starts to look "brutal" for the candidates who aren't the frontrunner.

On Super Tuesday, March 1, 25 percent of the delegates to the Republican national convention will be awarded. If the mainstream field hasn't been narrowed by that point, it will become very hard to avoid serious damage to the candidate who ultimately emerges as the party's anointed favorite. The top mainstream candidate could easily fall more than 100 delegates short of what he might have earned in a winnowed field. He would even be in danger of earning no delegates at all in several of the largest states because of one number: 20 percent.

There's still time for a lot of surprises. A lot of us thought Trump would win Iowa, for example, but he didn't. Few expected John Kasich to finish second in New Hampshire.

Maybe Nevada will offer unexpected results. Maybe South Carolina's Republican establishment and media hype can propel Rubio to victory on Saturday night. Maybe a lot of things.

But as we look ahead, as MSNBC's Benjy Sarlin

did quite well this morning, the calendar is going to apply intense pressure on candidates who are competing in these early nominating contests, but failing to finish on top.