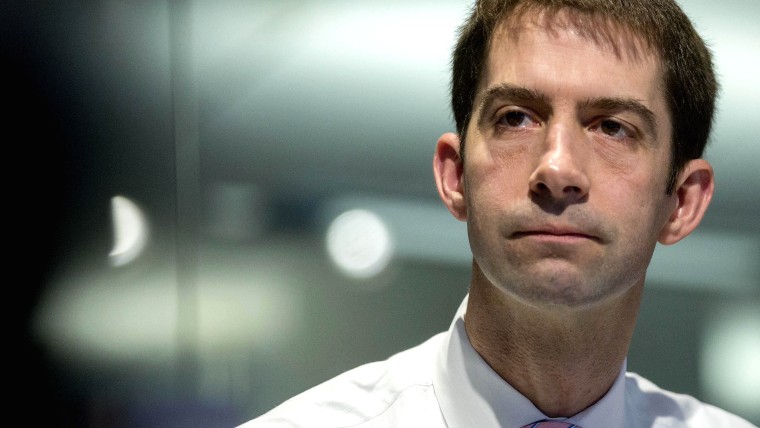

The year is off to an interesting start for Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.). The far-right Arkansan, suddenly a person of great influence with Donald Trump over immigration policy, has been accused of using dishonesty to help cover for the president; he's feuded with a Senate Republican colleague; and he's feuded with a Senate Democratic colleague.

The Washington Post ran a piece last week that said, in apparent reference to Cotton, "Credibility is like virginity. You only get to lose it once."

The Republican Arkansan is nevertheless undeterred. Cotton appeared on Hugh Hewitt's conservative talk show yesterday, and appeared to make a threat about Senate procedure. As MSNBC's Kasie Hunt noted, Cotton said that if Democrats take steps to block some Trump nominees, "we might be compelled to change the rules on our own."

Whether the GOP majority is seriously considering such a move remains to be seen, though it's worth pausing to appreciate just how breathtakingly hypocritical Cotton's complaints on the subject really are.

Indeed, it seems as if Cotton has forgotten how he treated Cassandra Butts. Perhaps now is a good time to remind him.

As regular readers may recall, in 2016, the New York Times’ Frank Bruni highlighted Cassandra Butts’ nomination to serve as the United States ambassador to the Bahamas.

After “decades of government and nonprofit work that reflected a passion for public service,” Butts received a nomination from Barack Obama to a diplomatic post for which she was well qualified. Her confirmation should’ve been easy, but the Senate kept putting her nomination on the back-burner – Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), for example, blocked her as part of a tantrum against the Iran nuclear deal.

And then there was Tom Cotton, who blocked Butts and two other nominees.

Cotton eventually released the two other holds, but not the one on Butts. She told me that she once went to see him about it, and he explained that he knew that she was a close friend of Obama’s – the two first encountered each other on a line for financial-aid forms at Harvard Law School, where they were classmates – and that blocking her was a way to inflict special pain on the president.

Bruni’s report added that Cotton’s spokesperson “did not dispute Butts’s characterization of that meeting.”

All of this became even more notable when Butts died at the age of 50 of acute leukemia, which she didn’t know she had until her life was nearly over. She waited 835 days for the Senate to vote on her nomination, but the vote never came.

“All Cassandra wanted to do was serve her country,” Valerie Jarrett, a senior adviser to the president, told the Times. “Looking back, it is devastating to think that through no fault of her own, she spent the last 835 days of her life waiting for confirmation.”

As we discussed at the time, this story got me thinking about the nature of public service, and how different people approach their responsibilities.

On the one hand, we see Cassandra Butts, who could have used her Ivy League education to go into the private sector and make a lot of money, but who chose instead to serve the public working on Capitol Hill, the White House counsel’s office, and various non-profit organizations, including the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

On the other hand, we see Tom Cotton, who thought it was responsible to use his Senate office to block Butts, not because of the merits of her nomination, because he wanted “inflict special pain on the president.” If that meant seeing Butts as little more than a pawn on a chessboard, so be it.

Both Butts and Cotton went to Harvard, and both chose careers in the public sector, even when the private sector would have been more lucrative. Indeed, Cotton’s congressional career has been brief, but he also had an impressive military career before entering politics, serving honorably in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At some point, however, Cotton convinced himself that using his office to “inflict special pain on the president,” rather than doing the right thing, was acceptable. The GOP politician came to the conclusion that treating a qualified nominee -- a human being -- this way was justifiable as part of a petty, partisan tantrum against a president he held in contempt.

Tom Cotton wants to talk about Senate obstructionism? Fine. Let's start with a conversation about Cassandra Butts.