Just last night, Rachel asked Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) whether the larger and more progressive Senate caucus might finally reform Senate filibuster rules in the new Congress. The senator replied, "I am so hopeful."

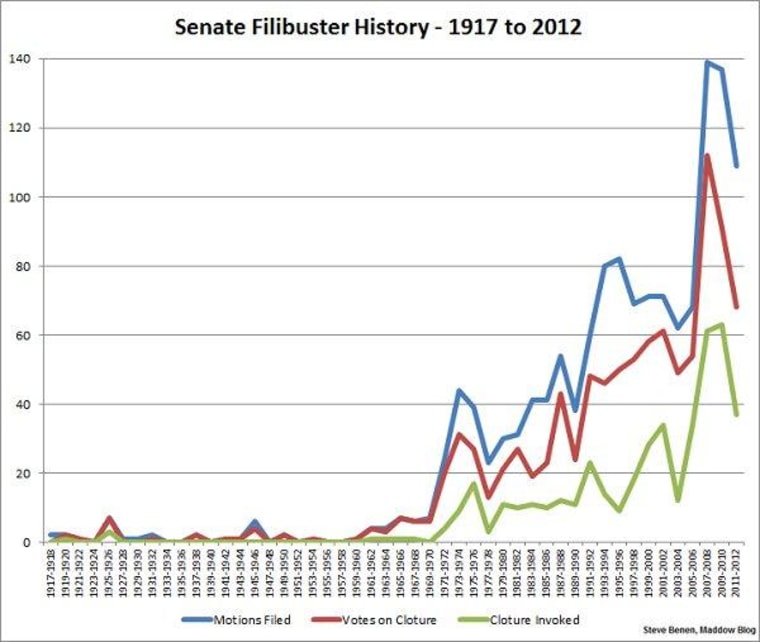

Given the need, Klobuchar isn't the only one. Take a look at this chart I put together on the growth in the number of filibusters since the Senate changed its rules in 1917.

The chart is based on an updated table the Senate keeps, chronicling cloture votes over the last nine decades, using three metrics: (1) cloture motions filed (when the majority begins to end a filibuster); (2) votes on cloture (when the majority tries to end a filibuster); and (3) the number of times cloture was invoked (when the majority succeeds in ending a filibuster). By all three measures, obstructionism soared over the last six years as Republicans abused the rules like no other party or caucus in American history.

You'll notice a sharp drop in the number of filibusters in the most recent Congress. While that might suggest signs of progress to some, it's not -- the drop only came as a result of the GOP-led House passing far-right bills the Senate didn't care to pass. And even despite this fact, the 112th Congress saw the third most filibusters of any Congress in the 223 years the Senate has existed.

In case this isn't obvious, the Senate wasn't designed to work this way; it didn't use to work this way; and by any credible measure, it can't work this way -- which is why there's so much talk of reforms next year.

Yesterday, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell's (R-Ky.) complained, "We hope Democrats will work toward allowing members of both sides to be involved in the legislative process -- rather than poisoning the well on the very first day of the next Congress."

It's important to understand why this is wrong.

According to McConnell's office, the only meaningful way for the Senate to operate with a cooperative legislative process -- one in which "both sides" are "involved" -- is for an obstructionist minority to have the power to require mandatory supermajorities on literally every vote of consequence.

That's absurd. The U.S. Senate functioned quite well for two centuries while operating under majority rule. To hear McConnell tell it, unless 41 senators can trump 59 senators, the institution will become a shell of its former self. In reality, reform simply clears the way for a return to Senate norms and traditions.

If Republicans didn't want to invite these changes, they shouldn't have twisted and abused Senate rules in ways previous caucuses never even dreamed of.

The New York Times editorial board had a good piece on this today.

The filibuster's importance is as a last-ditch ploy to prevent a minority party from being steamrolled on the most pressing national issues. It was never intended to routinely require a 60-vote supermajority on virtually every issue the Senate takes up. Yet that's how Republicans have used it in the last six years, to a far greater extent than Democrats ever did when they were in the minority.The proposal made by Mr. Udall and Mr. Merkley last year, which we strongly supported, would have preserved the filibuster but made it much harder to use. Rather than allow a single senator to raise an objection that triggered a 60-vote requirement, their plan would require 10 signatures to start a filibuster and would then force an increasingly large group of members to speak continuously on the floor to keep it going. Senators could not hide in cloakrooms but would have to face the public on camera to hold up a judge's confirmation, a budget resolution or a bill. [...]Mr. Reid has already expressed an interest in ending filibusters on "motions to proceed," a parliamentary tactic routinely used by Republicans to prevent debate on bills. That would reduce time-wasting in the Senate but would still allow supermajority barriers on the actual passage of bills. But he needs to go further, supporting the Udall-Merkley proposal to end "lazy filibusters" and to eliminate the filibuster on establishing House-Senate conferences, which has made negotiations increasingly rare.

So, what happens now? Policymakers are primarily focused on debt-reduction talks and negotiations to avoid automatic spending cuts and tax increases, but plans for institutional reforms will continue, largely out of sight. Greg Sargent reported last week that half the chamber is now on record supporting filibuster reform, but The Hill reports this morning that proponents still have some work to do.

"I haven't counted 51 just yet, but we're working," said Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.) said.

The biggest stumbling block? There are Democrats who want to be able to use Republican tactics the next time there's a GOP majority.