Bernie Sanders hoped a victory in the Nevada caucuses would change the direction of the Democratic race, but the results didn't turn out as he'd hoped. With nearly all of the votes counted, it appears Hillary Clinton won by about six points.

The Vermont senator commented yesterday morning about why he came up short.

"Voter turnout was not as high as I had wanted," Sanders allowed on NBC's Meet the Press, "and what I've said over and over again, is we will do well when young people when working class people come out, we do not do well when voter turnout is not large." [...] "We did not do as good a job as I had wanted to bring out a large turnout," said the senator.

The assessment seems perfectly fair, but the fact that turnout fell short of Sanders' hopes is part of a more alarming pattern: his entire candidacy is built on the premise that he, and he alone, can boost turnout in ways pundits and the political establishment fail to appreciate.

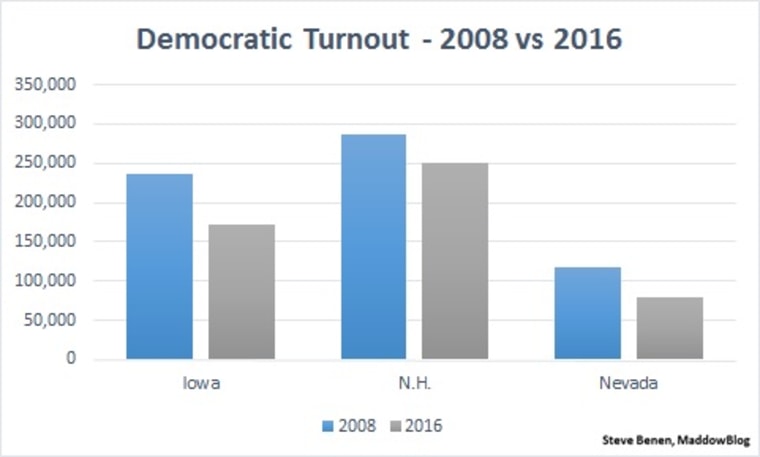

Except, after three contests, this element of Sanders' "revolution" is coming up short. This calls for a chart.

In the 2008 Democratic caucuses in Nevada -- the first year the contest existed in earnest -- turnout was roughly 120,000 voters. On Saturday, it appears turnout reached about 80,000 people, which represented a cycle-to-cycle drop of around 33%.

In Iowa, Democratic turnout went from roughly 236,000 in 2008 to about 171,000 this year, which works out to a 25% drop, while in New Hampshire, Democratic turnout went from about 288,000 in 2008 to roughly 251,000 this year, which is a drop of around 13%.

As we discussed after the New Hampshire primary, for months, Sanders' supporters have responded to concerns about the senator's electability by pointing to, among other things, the potency of his revolution: the independent senator's bold and unapologetic message will resonate in ways the political mainstream doesn't yet understand. Marginalized Americans who often feel alienated from the process -- and who routinely stay home on Election Day -- can and will rally to support Sanders and propel him to the White House.

The old political-science models, Team Sanders argues, are of limited use. Indeed, they're stale and out of date, failing to reflect the kind of massive progressive turnout that Bernie Sanders can create. It's this factor that will not only make him president, but also help Democratic candidates up and down the ballot.

But at least so far, in 2016 contests, Republicans have broken turnout records in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina, while Democratic turnout has gone down, not up, since the party's last competitive cycle.

I've seen some suggestions that comparing 2016 to 2008 isn't entirely fair because the Clinton-vs-Obama showdown was so epic eight years ago, driving voter excitement to new heights. But as we talked about, therein lies an important point: If a candidate like Bernie Sanders is going to win the presidency, he would need to be able to match and build on the kind of turnout Dems saw in 2008.

And so far, the numbers don't show that.

It's true, of course, that turnout models in primary and caucus elections differ from those in a general election. But at the core of Sanders' pitch is a non-traditional pitch: Democrats can take a chance on a 74-year-old democratic socialist, who'll win a national election thanks to his ability to bring more voters into the process.

If that isn't happening at this phase of the election, the gamble starts to look like an even greater risk. When Sanders and his proponents argue, "We're not boosting turnout now, but this will definitely work out in the fall," it's a pitch that's bound to face skepticism.

Update: The Washington Post's Greg Sargent had a very good piece on the larger dynamic, which is well worth your time.