There's a difference between what's mathematically possible and what's realistically probable. After Hillary Clinton won five of the six primaries in late April, it was still technically possible for Bernie Sanders to catch his rival among pledged delegates, but he'd need lopsided landslides in the May contests.

That hasn't happened. Narrow wins in Indiana and West Virginia helped Team Sanders with morale and fundraising, but they actually left him further from his goal. The same was true in yesterday's primaries, as MSNBC's Alex Seitz-Wald reported.

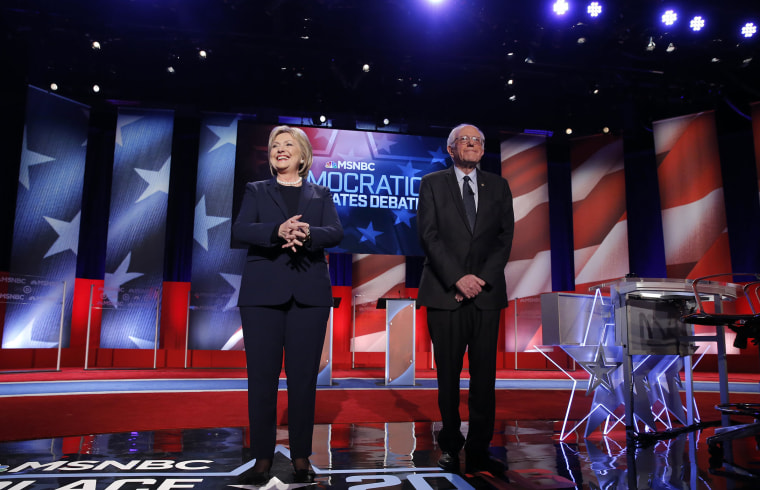

Bernie Sanders mini-winning streak ended Tuesday night in Kentucky, a state analysts expected he could win. The loss could take some wind out of supporters' sails at a critical time as they face increasing pressure to unify the Democratic Party behind likely nominee Hillary Clinton. But it was a mixed night for the candidates. Sanders pulled out a comfortable single-digit win in Oregon, where he is likely to walk away with a solid block of delegates.

In practical terms, the Kentucky results, while incredibly close, are about bragging rights: the difference between a narrow win and a narrow loss is negligible. Sanders needed a landslide victory to keep pace, and his apparent defeat pushed his goal that much further away. Similarly, while the senator's success in Oregon was no doubt satisfying, Sanders' margin of victory was actually quite a bit smaller than Barack Obama's 2008 win in the same state, and to keep up with Clinton, it needed to be more than four times larger.

Yesterday, in other words, represented another major setback for the Sanders campaign: his win was too narrow, his loss was a step backwards, and the number of remaining opportunities he’ll have to close the gap continues to shrink.

The Vermonter continues to tell supporters that he might win the Democratic nomination. In remarks last night, Sanders said he faced a "steep climb," but he nevertheless believes he can wrap up the primary process with a majority of pledged delegates.

Which brings us back to the "mathematically possible" vs. "realistically probable" problem.

There are six primaries (California, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, South Dakota, and D.C.) and three caucuses (Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and North Dakota) remaining. In some of these races, Clinton is very likely to win, but let's say Sanders instead runs the table. In fact, let's say for the sake of conversation that the senator goes nine for nine, and wins every contest by 30 points.

He'd still lose the race for the nomination. That's how big Sanders' current deficit is.

None of this, by the way, has anything to do with superdelegates. We're talking only about pledged delegates, earned exclusively through nominating contests decided by rank-and-file voters.

"Don't tell Secretary Clinton, she might get nervous -- I think we're going to win California," Sanders boasted last night. Polls show him trailing in the Golden State, but even if we assume they're wrong, the question has little to do with whether or not Sanders can win the California primary. Instead, the question, as MSNBC's Steve Kornacki explained on the air last night, is whether he seriously expects to win by 50 points.

A "steep climb," indeed.