Arguably no single development in American politics has mattered more in recent generations than the radicalization of the Republican Party. As anyone who's read Tom Mann and Norm Ornstein knows, the GOP's shift to the far-right has fundamentally remade the policy landscape and changed the nature of the political rules in ways nothing -- no scandal, no crisis, no war -- has in many decades.

At least, that's what all available evidence tells us. Peter Wehner, the White House director of "strategic initiatives" in the Bush/Cheney era, not only disagrees with the thesis, but actually suggests the evidence has it backwards -- it's Democrats, he claims, who've become more extreme. From his New York Times piece today:

Among liberals, it's almost universally assumed that of the two major parties, it's the Republicans who have become more extreme over the years. That's a self-flattering but false narrative. This is not to say the Republican Party hasn't become a more conservative party. It has. But in the last two decades the Democratic Party has moved substantially further to the left than the Republican Party has shifted to the right. On most major issues the Republican Party hasn't moved very much from where it was during the Gingrich era in the mid-1990s.

Intrigued, I dug into the piece, eager to see Wehner's proof. He noted, for example, that while many Democrats embraced a conservative approach to criminal-justice reform 20 years ago, most Dems are now widely concerned about the societal costs and effects of mass incarceration and police abuses.

I'm afraid Wehner hasn't fully thought this through. Democrats adopted a position, implemented it, and are now weighing changes after scrutinizing the results of their own policy. Plenty of Republicans agree with the Democratic conclusions, and support the same reforms. That's proof of a party that's become more extreme? Not by any definition I'm familiar with.

Well, maybe Wehner's piece just got off to a rough start. How about his second piece of evidence? The piece soon after complains that while Bill Clinton reformed welfare, President Obama created the Affordable Care Act.

Perhaps Wehner hasn't fully thought this through, either.

Presidents of both parties have been talking for a century about bringing health security to American families, and Obama succeeded where others failed. If the president and congressional Democrats imposed a socialized system -- Medicare for All, for example -- Wehner might have a more credible case to make, but "Obamacare" is a more conservative model, largely dependent on private insurers, based in part on a blueprint drafted by the Heritage Foundation.

As for welfare reform, Obama has left the '90s-era policy largely intact.

Again, this doesn't sound like the actions of a party that's gone over the left-wing cliff.

From there, Wehner's oddly written piece descends into a litany of praise for Bill Clinton, who apparently did a series of things conservatives liked, right up until Wehner's former boss created a mess that Democrats had to clean up. At one point, Wehner dabbles in outright falsehoods: "Mr. Clinton cut spending and produced a surplus. Under Mr. Obama, spending and the deficit reached record levels."

In reality, Clinton may have left Bush/Cheney with a surplus, but Bush/Cheney then left Obama with a $1.4 trillion deficit, which Obama has already trimmed by $1 trillion (and counting).

If the broader point is that Obama has helped move the country to the left a bit, I'll gladly concede the point -- just as I'd say Reagan helped move to the country to the right a bit a generation ago. But Wehner's thesis is about extremism and radicalization, and to bolster the thesis, he manages to point to exactly zero examples of Democrats becoming extreme and/or radical when compared to the American mainstream.

(Wehner mentions gay rights 4 times in a 14-paragraph piece, neglecting to mention that, by definition, there's nothing less extreme than agreeing with the American majority. Indeed, Obama may be the most ambitious supporter of gay rights of any president in history, but his leadership on the issue has kept pace with the nation's own evolution. Obama is well to Clinton's left on the issue, but 2015 America is also well to the left of 1995 America on the issue.)

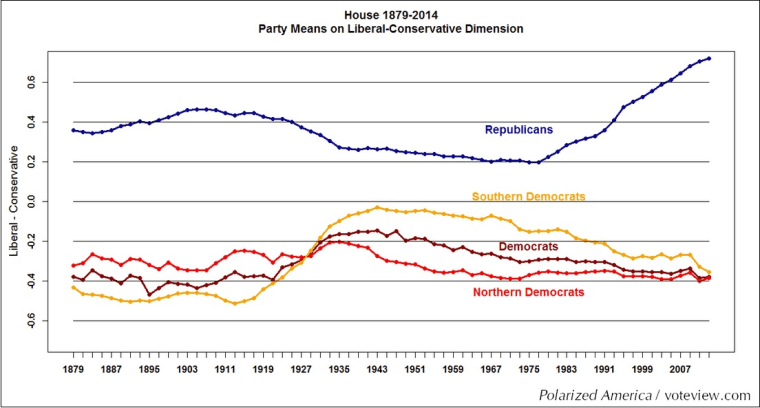

We're left, in other words, with the challenge of reconciling Wehner's impressions and quantifiable evidence, such as these DW-NOMINATE scores, which clearly help prove the opposite of the Republican's intended conclusion.

I often wonder how GOP insiders deal with the objective evidence highlighting the radicalization of Republican politics, but Wehner's strange thesis suggests they're not dealing with it at all. Rather, they're content to pretend that Democrats -- the mainstream party open to compromise, embracing Mitt Romney's health care plan, John McCain's climate plan, George W. Bush's immigration plan -- are the real extremists.

There has to be a more persuasive Republican case than Wehner's. If anyone has seen one, let me know in comments.