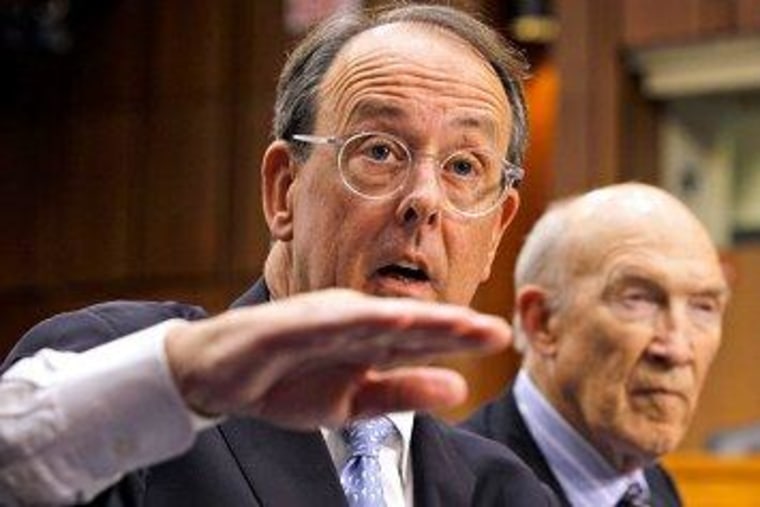

We talked in some detail yesterday about the flaws in the latest debt-reduction plan from former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.) and Erskine Bowles (D-N.C.), the folks celebrated by the political/media establishment as sage voices on fiscal issues for reasons I've never been able to identify. The Simpson-Bowles 2.0 plan probably isn't going anywhere, but before we move on, Tim Noah flags a detail I'd overlooked.

It turns out, in their drive to reduce deficits, Simpson and Bowles want to lower tax rates, replacing the revenue with scaling back "most" tax expenditures. It's not unreasonable to wonder why in the world the so-called deficit hawks would do this.

Lowering income-tax rates while eliminating tax breaks would, Simpson and Bowles say, achieve some unspecified quantity of deficit savings. But if your aim is to reduce the deficit, why not get rid of as many tax expenditures as you can while leaving tax rates constant -- or, better yet, raising them a bit? Simpson and Bowles would likely say they're just being realistic about politics. Republicans won't eliminate loopholes unless they can lower rates, too.But as long as we're being realistic, why not be realistic about the likelihood that a lower-rates-for-fewer-loopholes swap will reduce the deficit? Which is about zero. Simpson and Bowles's insistence on clinging to the tax-reform fantasy demonstrates that their agenda is not limited to deficit reduction. They also want to lower tax rates. Why? They just want to, is all.

Quite right. One of the long-standing complaints against Simpson-Bowles is that their debt-reduction plan isn't solely about reducing the debt. The fact that their newest blueprint cuts taxes, for no apparent, reinforces the concerns.

In the broadest possible sense, there are limited options when it comes to reducing Washington's budget shortfall: the federal government can collect more revenue, it can spend less money, or it can try to strike a balance between the two. If a plan brings in less revenue, on purpose, then it moves further from the intended goal, not closer to it.

Simpson-Bowles seems to accept the basic premise, but nevertheless wants to devote some new revenue from vague tax-reform measures, not to reducing the deficit, but to more tax cuts.

Worse, they make this recommendation without explanation. Perhaps they think it's obvious that tax cuts are a good idea.

And if they want to make that case, fine, we can have the debate and point to the flaws in their assumption. But let's not keep up the charade that Simpson-Bowles is purely about fiscal responsibility, when there's also clearly a conservative ideological goal underpinning parts of the outline.