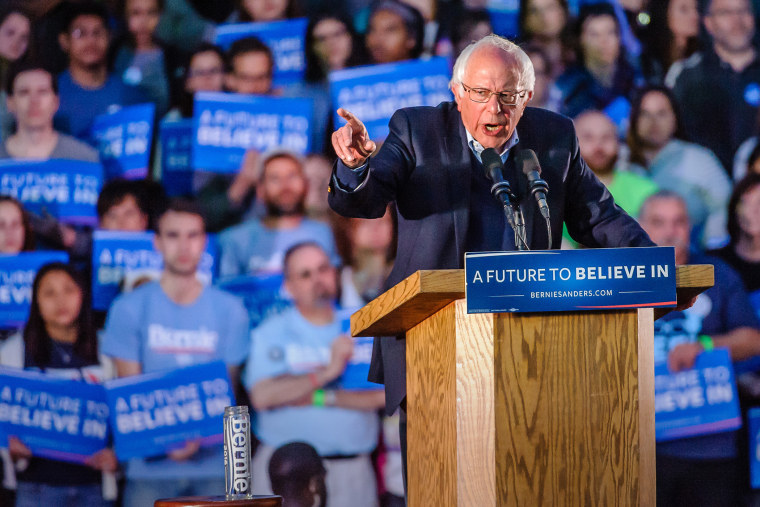

The road ahead for the Bernie Sanders campaign has been difficult to discern of late. Yesterday brought unexpected clarity.

Two weeks ago, Sanders' campaign manager, Jeff Weaver, told MSNBC that the senator would "absolutely" take the Democratic race to the convention, even if Sanders loses the fight for pledged delegates and popular votes. The plan, Weaver said, is to ensure that the race is "determined by the superdelegates."

Soon after, however, Sanders' chief strategist, Tad Devine, told Rachel that the campaign plan is actually quite different. As Devine described it, Team Sanders believes superdelegates should "follow the will of the voters." In practical terms, given Hillary Clinton's advantage, Devine was describing a scenario in which the Sanders campaign would accept the outcome of the primaries and caucuses.

So, which of these aides was correct? The Vermont senator himself shed light on his plans at a press conference in D.C. yesterday.

Bernie Sanders said on Sunday that he and Hillary Clinton were heading to a "contested" convention this summer because she will need superdelegates to secure the nomination, a claim that clashes with the accepted definition of a contested convention. He also said that superdelegates who have supported her should switch to him instead. At a news conference in Washington, Mr. Sanders said that the Democratic convention in July would be contested because "it is virtually impossible for Secretary Clinton to reach the majority of convention delegates by June 14 with pledged delegates alone," and that she "will need superdelegates to take her over the top." He added: "In other words, the convention will be a contested convention."

Of particular interest, Sanders pointed to states where he was successful at earning voters' support, though party officials from those states are nevertheless backing Clinton. He pointed specifically to the state of Washington, where Sanders won a huge landslide victory, but where the state's 10 superdelegates continue, at least for now, to support his opponent.

"If I win a state with 70 percent of the vote, you know what? I think I am entitled to those superdelegates," Sanders said yesterday. "I think the superdelegates should reflect what the people of the state want, and that's true for Hillary Clinton as well."

That's hardly an outrageous argument. Under the rules, superdelegates are allowed -- and by some measures, encouraged -- to exercise their own judgment, but Sanders' point seems reasonable enough. Perhaps there should be some correlation between the judgment of a state's voters and the attitudes of the state's superdelegates?

But Sanders' supporters should be cautious about embracing this line too enthusiastically: if every superdelegate voted in line with their state's primary or caucus, Clinton would still enjoy a comfortable lead. Indeed, as the New York Times' Nate Cohn noted, under the standards Sanders presented yesterday, Clinton would have locked up a majority of all available pledged delegates last week.

In other words, Sanders yesterday endorsed a dynamic that wouldn't actually improve his odds of success.

As for the larger context, when Jeff Weaver argued that superdelegates should elevate Sanders, even if that means overriding the primary results and defying the will of the voters, it was considered pretty controversial. As of yesterday, however, Sanders at least claims to be on board with the same plan.

It's possible, of course, that Sanders will reconsider. The primary process doesn't wrap up for another six weeks, and when that phase ends, the senator may take stock, reevaluate his standing, and conclude there's no practical reason to dragging out the process unnecessarily -- especially if there's little reason to believe party officials will disregard the results of the primaries and caucuses. By mid-June, perhaps Weaver's approach will fall out of favor and Devine's approach will prevail.

But at least for now, Sanders has committed to a provocative gambit, pushing for a "contested convention" in which he'll ask party insiders to see him as the better candidate -- even if Democratic voters make a different determination.