Reaching outside the African-American community to broaden my perspective has been an important element in my transformation and growth in the past two decades as a human rights activist.

In the Brooklyn neighborhood where I grew up, I was surrounded by immigrants. Haitians, Jamaicans, Trinidadians, Dominicans, Nigerians, Senegalese—you couldn’t walk down the street without tripping over interesting folks, and interesting foods, from across the globe. Like everybody else in America, these people were striving to work hard, send their children to the best schools possible, and trying to grab their little piece of that elusive American dream.

So when the issue of immigration began to emerge as an explosive political football, my thoughts would drift back to the streets of Brooklyn. These were real people—people who were a part of me. For me, it could never be them against us. My upbringing undoubtedly compelled me over the years to be naturally inclined to fight for immigrants’ rights and to try as much as possible to build coalitions between African-Americans and the immigrant community, understanding that our plights in America were intertwined, particularly as the government moved toward increased racial profiling to enforce its repressive immigration policies.

Of course, for too many Americans, fed a steady stream of threatening media images, the word immigrant conjures visions of frightened Mexicans scurrying across the dusty Arizona desert, hoping to slip unseen into American society and immediately become a drain on the American pocketbook. That’s become the handy American archetype. You can hardly hear the word immigrant without first being accosted by the word illegal. In a country founded by immigrants, the ultimate irony is that America has now permanently attached the disturbing descriptor illegal to the word that defined our ancestors.

Immigrant. It didn’t use to be a dirty word, not when the shiploads came into Ellis Island on those steamers from Europe, blessed by the words of poet Emma Lazarus on the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

I can’t help but note, as many others have before me, that this country didn’t have an “immigration problem” until the immigrants became overwhelmingly black and brown. In 1960, the top five countries sending immigrants to the United States were Italy, Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Poland. I don’t recall presidential candidates back then being forced to come up with a stance on Italian, German, or Canadian immigrants.

But by 1970, Mexico had entered the top five. By 2000, when immigration had become an explosive third rail of American politics and there was talk of building electrified fences along the southern border, the top five looked very different: Mexico, India, China, the Philippines, and Cuba. It’s not difficult to see the difference between the two lists.

Dr. King was a giant of the civil rights movement, but let us not forget the courageous work of Cesar Chavez, who adopted some of the nonviolent tactics of Dr. King to fight on behalf of migrant farmworkers. With boycotts, strikes, and the creation of the United Farm Workers union, Chavez awoke the world to the exploitation of Latino farmworkers in the Southwest. King and Chavez were also friends and associates who understood the common purposes of their struggle for human rights for black and brown Americans. What happened to the spiritual bond formed by these two great leaders?

I have been disturbed by how quickly forces in the African-American community have succumbed to brainwashing, to wrongheaded propaganda about this issue. When I hear black people repeating this nonsense, saying, “They’re taking our jobs,” my first response is to ask, “What jobs?” Ever since there have been labor statistics recorded in this country, blacks have been doubly unemployed; our rate has always been double the national rate. The only time black people had full employment in the United States was during slavery—and we didn’t get paid. So who was taking our jobs before we had an influx of Mexicans over the past thirty-five or forty years? This country has never intended for blacks to be fully and gainfully employed, and that has nothing to do with Mexicans. So let’s stop the blame game and try to focus on the big picture here.

I was thinking about the need for me to move outside of my comfort zone when I made the decision to join my Puerto Rican brothers and sisters in their protests against the U.S. Navy’s bombing in Vieques, a small island next to Puerto Rico. I was trying to reach out, to grow, and in the process, I stumbled into one of the most difficult ordeals that I’ve had in my career. I wound up spending three months in jail because of the Vieques protests. Although it was a harrowing ordeal, that time also turned out to be incredibly important to me, giving me an opportunity to do some serious introspection and planning. I would be a totally different person and a different leader today had I not gone through the Vieques experience. It was surely one of the most impactful three months of my life, setting the stage for much that was to come later.

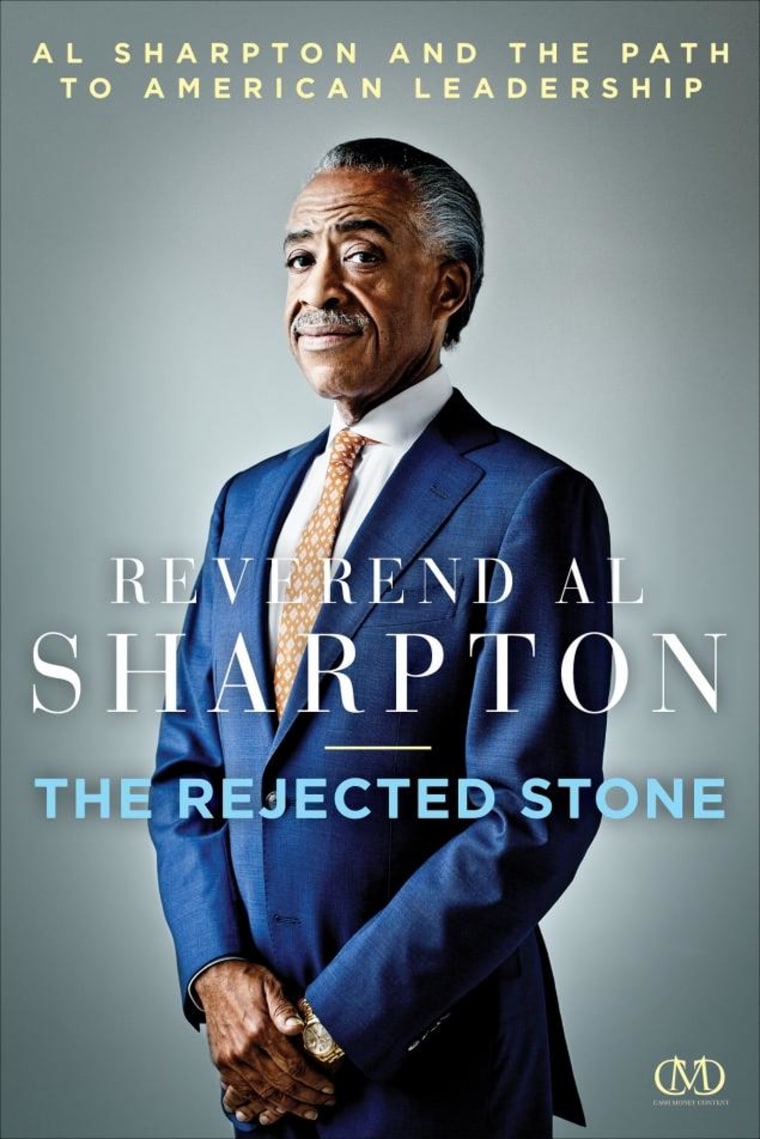

Rev. Al Sharpton’s new book, the Rejected Stone, comes out October 8.

Pre-order from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

RSVP to attend the book signing at noon on October 8 in New York City at the Barnes & Noble on Fifth Avenue between 45th and 46th streets.