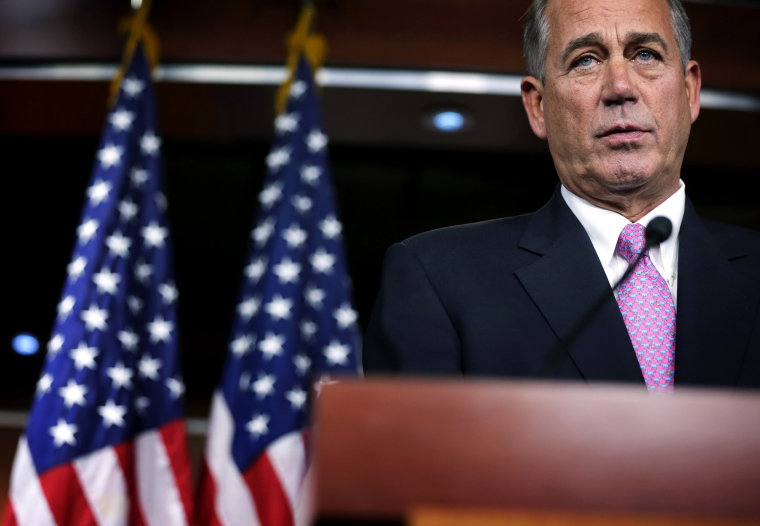

As recently as last August, congressional Republicans were still insisting that any increase in the federal government’s debt limit would have to be matched, dollar-for-dollar, by spending cuts. Indeed, Speaker John Boehner said the cuts should exceed the debt-limit increase.

This was an extreme position to take, risking U.S. default on its financial obligations. But the risk was worth it, the House GOP felt, because the federal deficit simply had to be brought under control. As Rep. Paul Ryan had said during the 2012 presidential campaign: “Of all the broken promises from President Obama, this is probably the worst one, because this debt is threatening jobs today, it’s threatening prosperity today, and it is guaranteeing that our children and grandchildren get a diminished future.”

RELATED: The GOP's debt-ceiling farce

Then, in October, the House GOP decided no, what it really wanted was to kill off Obamacare by delaying its implementation one year. The scale was less ambitious, but the ideological message was the same: Republicans oppose big government.

When the government shutdown abruptly plunged Congress’s approval ratings into uncharted depths, the GOP started angling for smaller concessions. It wanted to delay Obamacare’s individual mandate. It wanted to eliminate Obamacare’s birth control coverage. It wanted to repeal the medical-device tax. In the end, it got essentially nothing.

Now the debt ceiling is expiring again and House Republicans don’t know what they want. According to Reuters, they would still like to do something “to reduce deficits or boost economic growth.” For Republicans, that never means anything except spending and tax cuts.

But the actual package they’re putting together includes neither. Instead, House Republicans are demanding that the debt-limit increase be tied to spending increases for military retirees and for physicians who treat Medicare patients. The pension cut was part of a bipartisan budget deal worked out a mere two months ago.

Congressional Republicans would like you to know that the increases they now propose will not be net increases; spending cuts will be found to offset them. And, to be sure, the Medicare “doctor fix” is an increase that Congress routinely makes to compensate for a faulty cost-control measure (the “Sustainable Growth Rate”) implemented back in 1997. The military pension increase will be offset at least in part by increased pension contributions.

Still, until fairly recently the House GOP insisted that the sole reason to hold up a debt-ceiling increase was to enforce spending discipline, not to cut a little spending here so you could increase a little spending there. This is an emergency, right? Granted, we no longer have trillion-dollar deficits. But we still have a half-trillion-dollar deficit.

The House GOP’s new debt-limit demands raise the powerful suspicion that its purpose these past few years, in playing chicken with government default, was never to limit government spending. It was just to mess with Obama. The strategy won Republicans spending concessions early on, but October’s government shutdown proved a complete fiasco for them. Now they’re just trying to show that they can get something—anything--out of Obama. What that something is scarcely matters.

Soon after the October shutdown began, Rep. Marlin Stutzman, R-Ind., blurted out to the Washington Examiner, “We have to get something out of this. And I don’t know what that even is.” Now that lament is the official position of the House GOP. They want something in return for keeping the U.S. Treasury out of default. They’re no longer (and probably, deep down, never were) terribly interested in what that is. It’s a lousy bargaining position, and an even lousier justification for years of damaging equivocation about whether Congress would fulfill its responsibility to pay its bills.