NDJAMÉNA, Chad -- "It took 24 years, but I finally got to face down the man who threw me in prison,” said Souleymane Guengueng with a big grin outside the courthouse in this dusty capital. “He couldn’t even deny what he did.”

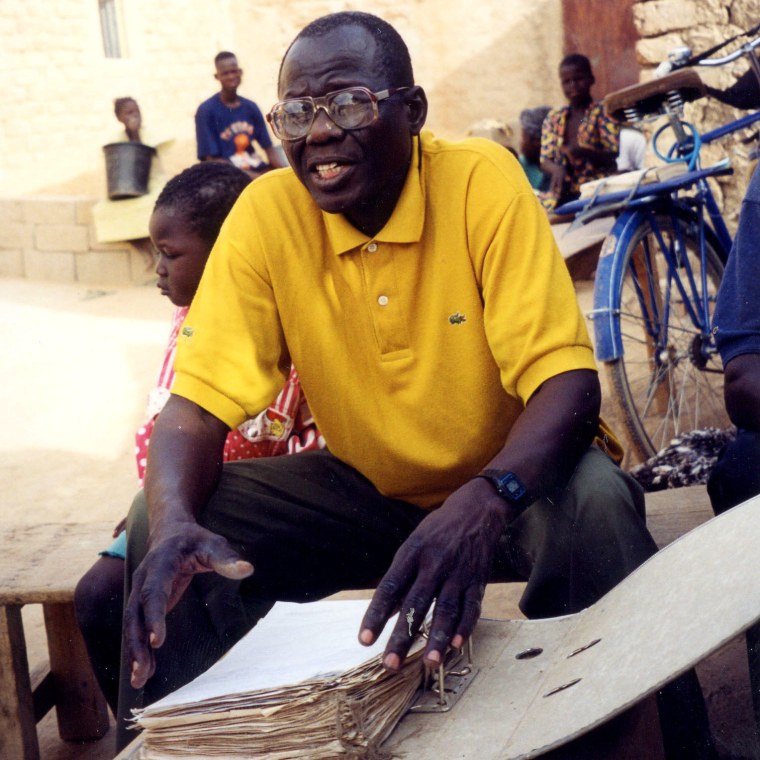

Guengueng, who barely survived two-and-a-half years of mistreatment in the dungeons of former dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré, swore that if he got out alive he would bring his jailers to justice. When Habré was overthrown in 1990 by the current president, Idriss Déby Itno, and fled across the continent to Senegal, Guengueng rallied wary survivors and widows to his quest for justice. Twenty-one officials of Habré’s political police -- the dreaded DDS -- are now standing trial here, while Habré himself is in pre-trial detention in Dakar, Senegal.

"Many in the courtroom wept when a video was projected showing a series of mass graves, the inside of Habré’s jails ..."'

Habré’s government is accused of thousands of political killings and systematic torture. But it took two decades of campaigning by the victims before Senegal and the African Union established special chambers in 2013 to try crimes committed under Habré. The Chadian authorities, not wanting to appear laggard, quickly followed suit by dusting off Guengueng’s 2000 complaint in Chadian courts and jailing dozens of Habré’s henchmen, many of whom were still serving as police chiefs and government officials.

None of that has dampened the ardor of the survivors, who have relished the chance finally to confront their tormentors in this trial, which has been going on since November. Mahamat Bechir Djidda described in court how the police chief at the time, Issa Idriss, burned Djidda with a cigarette as he was chained to the wall. Mallah Ngaboli said that Khalil Djibrine, known as "Khalil the Butcher," dragged Ngaboli behind a moving car. Hundreds of victims and widows in the audience hang on every word. Many in the courtroom wept when a video was projected showing a series of mass graves, the inside of Habré’s jails, drawings of the main forms of torture, and footage of emaciated prisoners released at Habré’s fall.

In 2014, the Chadian government, which had helped finance the Senegalese Chambers, seemed to get cold feet about the foreign investigation. President Déby, who had once been Habré’s military chief, was said to fear he would be implicated. He refused to transfer two key DDS suspects to Senegal and, perhaps to justify that refusal, rushed them to trial here, together with 22 others, with such haste that the indicting court didn’t notice that three of the defendants had been long dead.

Perhaps the most courageous person in the courtroom, though, is Jacqueline Moudeina, the Chadian lawyer who has guided the victims since 2000 and leads their case here. This icon of dignity narrowly survived an assassination attempt by one of the men on trial, and grenade shrapnel is still lodged in her leg.

The defendants for the most part have denied any brutality, and the hasty investigation means that no real record was prepared and new plaintiffs come forward each day – to the loud complaints of the defendants’ lawyers. In addition, because the court has strangely called no outside witnesses, it is sometimes the survivor’s word against the agent’s.

But Moudeina has an ace up her sleeve – tens of thousands of DDS files that detail what each DDS unit did. I stumbled on them in 2001, and Guengueng’s association later spent months organizing them for entry into a database. The documents list 1,208 dead prisoners and 12,321 victims of other abuses. They also report torture. "It was in compelling him to reveal certain truths that he died on October 14 at 8 o'clock" said one report. In another, the prisoner "only admitted certain facts that had been alleged against him after physical discipline was inflicted upon him."

The trial is also yielding information on U.S. support for Habré, seen by Ronald Reagan as a bulwark against Libya's Moammar Gadhafi. The U.S. covertly supported Habré’s ascension and backed him until the end. Saleh Younous, the former DDS director, told the court he was “aided constantly by a CIA agent." (To its credit, the Obama administration has been one of the strongest supporters of bringing Habré to justice.)

This trial is a kind of a warm-up for the main event -- Habré’s own trial, which is expected to begin in Senegal in May. Fortunately, that one has been better prepared. In 18 months, the chambers’ investigators have interviewed about 2,500 witnesses, analyzed the DDS documents, assigned experts to dissect Habré’s command structure and uncovered mass graves. That case, described by the French newspaper Le Monde as “a turning point for justice in Africa,” will be the first time the courts of one country try the leader of another for alleged human rights crimes. Even the trial here in Chad, though flawed, is a direct result of the Senegal case against Habré.

When Guengueng began his campaign, “everyone thought that I was crazy.” But now, he says, “we are showing them that justice is possible.”

Reed Brody, counsel with Human Rights Watch, has worked with Hissène Habré’s victims since 1999.