When thousands flock to Sochi, a 30-mile stretch of city that’s been transformed from the balmy “Russian Riviera” to a fake snow-topped “Winter Wonderland,” athletes, journalists, world leaders, and spectators will experience the best Olympic spectacle money can buy.

At an estimated cost of $50 billion, it better be.

But beyond the record price tag, the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia, come at what human rights activists are calling an unquantifiable human cost in exploitation and abuse -- one to which the International Olympic Committee has largely turned a blind eye.

“A lot of workers have felt trapped,” said Jane Buchanan, associate Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch, which last year documented an extensive list of violations based on interviews with 66 migrant laborers.

“They felt trapped by the expectation that they would be paid,” Buchanan said. “Some were trapped because employers were withholding passports or identity documents.”

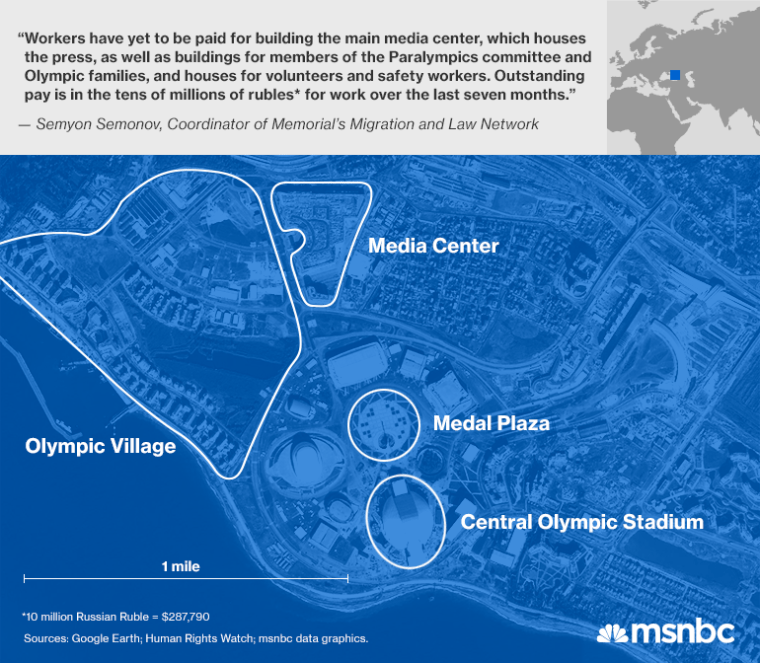

Since 2007, when Russia won the coveted bid to host next month’s Winter Games, thousands of laborers have traveled to Sochi--a Black Sea resort community and one of the warmest places in the country--to build two clusters of venues, packed with over 100 Olympic sites. They came looking for work from countries like Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. But hundreds have since complained about lack of pay, excessive hours, overcrowded housing, inadequate food, and, in recent months, unlawful detentions and hasty deportations.

Both Russian and Olympic officials have acknowledged the existence of wage irregularities, but insist that the problem has been dealt with. Russian authorities have suggested that immigration irregularities vastly outweigh those related to pay and stand by their right to deport migrant workers in the country illegally.

"The Russian government has the right to have a migration policy and enforce it," conceded Buchanan. "What they can't do is violate people's rights in the process of detaining and deporting them."

Semyon Semonov, who runs a local workers’ rights organization in Sochi, has seen these abuses firsthand. As coordinator of Memorial’s Migration and Law Network, he’s accounted for over 700 laborers who have not been paid. When trying to resolve these problems, Memorial has been met by government officials with indifference and, at times, even aggression.

“In July of 2013, we underwent an inspection by authorities from the Federal Security Bureau, prosecutors, and tax inspectors,” Semonov told msnbc via email. “This took place on the day after I submitted a complaint of the largest violation [of] migrant worker rights, having to do with almost 300 affected workers.”

“When we brought up the complaints of inhumane treatment workers have faced,” he continued, “the Investigative Committee not only refused to hear our claims, but also remarked: ‘We don’t have a Guantanamo here; that’s where they have inhumane treatment.’”

Beginning in September, Moscow has cracked down on the country’s undocumented immigrant population, and in the process targeted hundreds of Sochi workers for expulsion, sometimes without providing access to lawyers or interpreters. Many had travelled from neighboring countries in Central Asia, and were brought in by middlemen to work for lower wages than would be acceptable to Russian citizens. Their persecution, activists fear, indicates a rising tide of nationalism and xenophobia that has swept the country since Vladimir Putin regained the presidency in 2012, enacting a series of restrictive policies on the press, non-government organizations, and LGBT rights, to name a few.

“The government has systematically been cracking down on all sorts of civil society rights,” said Susan Corke, head of Eurasia/Russia programs at Freedom House. “It’s contributed to an environment where violence and discrimination and nationalism are given more space, and [people] with non-slavic appearances become a target.”

Exploitation, particularly of migrant workers, in Russia’s construction industry is nothing new. Human Rights Watch had uncovered many of the same problems in a 2009 report that looked at several cities. What was surprising about the recent spate of abuse was that it happened in the making of Olympic venues, supposedly under the watchful eye of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Organising Committees for the Olympic Games (OCOGs.)

When asked about whether an investigation into workers’ rights violations took place, both the IOC and the OCOG pointed to a recent check by Russian authorities that found some seven firms working on Sochi sites owed their employees over $8 million in unpaid wages. Those wages had been paid back in December, Deputy Prime Minister in charge of running the Olympics Dmitry Kozak announced, to the apparent satisfaction of Olympic officials, who did not say whether they had conducted an independent investigation into the matter. (One area in which the OCOG did put pressure on Moscow was in making sure Sochi hotel managers and staff attended “hospitality workshops” to train them in smiling at strangers.)

Human rights advocates remain suspicious of the government’s check, and disappointed with the IOC’s deference to Russian authorities.

“The government found this at basically the 11th hour,” said Buchanan. “If they’d been carrying out inspections all along, why would the government be turning up this scale of abuse in December?”

“The concern is that the IOC has not pushed the authorities enough,” she continued. “They simply take their word for it, and just act as bystanders.”