Texas didn't discriminate against minority voters. It was only because they were Democrats. And even if it did, the racial discrimination Texas engaged in is nowhere near as bad as the stuff that happened in the 1960s.These are some of the arguments the state of Texas is making in an attempt to stave off federal supervision of its election laws. In late July, citing the state's recent history of discrimination, the Justice Department asked a federal court to place the entire state back under "preclearance." That means the state would have to submit its election law changes in advance to the Justice Department, which would ensure Texas wasn't disenfranchising voters on the basis of race.This week, Texas submitted a brief arguing that placing the state back under preclearance would be an "extreme" encroachment on state sovereignty and denying that they ever discriminated against minority voters in the state."I don't think it's going to work, frankly. The mere desire to achieve partisan advantage does not give Texas a free hand to engage in racial discrimination," says Brenda Wright, a voting law expert with the liberal think tank Demos. "If the only way you can protect white incumbents is by diluting the voting strength of Hispanic citizens, you are engaging in intentional racial discrimination, and the courts will see that."

Related story: Conservatives prepare to finish off the Voting Rights Act

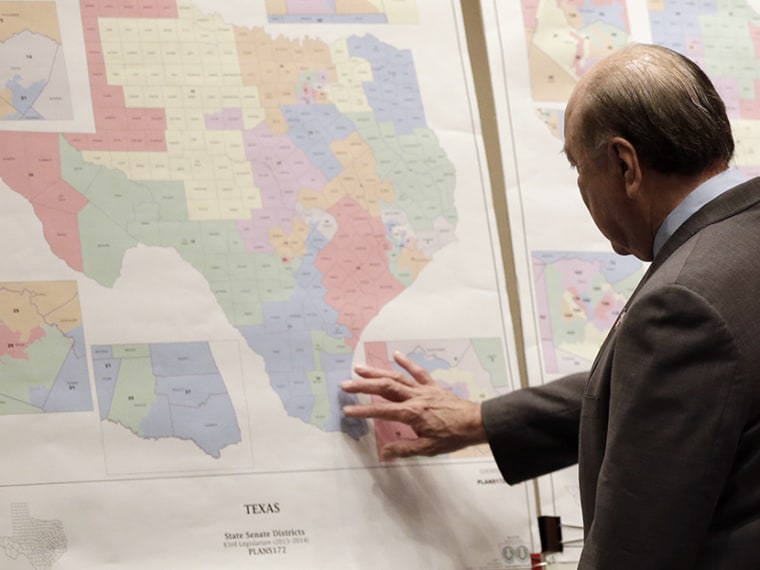

The Supreme Court struck down section 4 of the Voting Rights Act in June, the part of the law that determined which states have to go through preclearance. Section 3 of the law however, allows states with recent histories of deliberate discrimination on the basis of race to placed under preclearance again. A different federal court found that Texas' Republican-dominated state legislature had deliberately discriminated against minority voters with their 2011 redistricting plan, which diluted minority voting strength in an effort to give GOP candidates the upper hand. Texas though, says the legislature's actions weren't about race, they were just partisan politics.The Texas case is a key test for voting rights advocates of whether, and to what degree, section 3 can patch up the damage caused by the Supreme Court's ruling. Even if the court sides with voting rights advocates and the Justice Department, it could place Texas under a limited preclearance regime where they'd only have to submit specific voting law changes in advance rather than all of them.Shortly after the Supreme Court's Voting Rights Act decision, Texas moved to reinstate restrictive voting laws that had previously been blocked by the feds. As far as it's 2011 redistricting plan goes, the state's brief argues that's all in the past, and it was a partisan issue rather than a racial one anyway."The redistricting decisions of which DOJ complains were motivated by partisan rather than racial considerations, and the plaintiffs and DOJ have zero evidence to prove the contrary," the state writes in its brief. "It is perfectly constitutional for a Republican-controlled legislature to make partisan districting decisions, even if there are incidental effects on minority voters who support Democratic candidates."

Related story: House GOP's half-hearted first attempt to patch Voting Rights Act

Furthermore, the state claims, even if Texas did discriminate, and the state stresses that it did not, it was nothing as bad as "the 'pervasive,' 'flagrant,' 'widespread,' and 'rampant' discrimination that originally justified preclearance in 1965." So as long as Texas skies aren't alight with flames from burning crosses, what's the big whoop?Texas actually wasn't included in the original southern states placed under preclearance in 1965. Texas came under preclearance during the 1975 reauthorization of the law. Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, in her speech arguing for Texas to be covered by preclearance, didn't just discuss the obvious discriminatory practices that existed in the South before 1965. She talked about "school boards which have been abolished or reduced in order to prevent minority membership," and "polling places removed without notice," and "annexation by cities and counties to dilute minority votes." That is, attempts to disenfranchise minorities less overt than the ones Texas is claiming would be necessary to justify placing the state under preclerance again."There's an irony there that the standard that they're suggesting now is a standard which would have prevented Texas from being covered in the first place," notes Rick Hasen, a professor at the University of California-Irvine School of Law and author of the Election Law Blog.Since being placed under preclearance, Texas has amassed a rather poor record. According to a 2006 study by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the state was second only to Mississippi in the number of election law changes that were blocked by the feds, and more voting rights lawsuits under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act were brought in Texas than any other state.

Related story: The secret weapon that could save the Voting Rights Act

"If any states' history of voting discrimination would justify preclearance as a judicial remedy, certainly Texas is one of those states," says Wright.Texas' argument however, has larger implications, because it suggests only the conditions that existed in 1965 could justify close federal supervision of state election practices."They're arguing that the bail in remedy is no longer permissible, and I think that is a stretch," says Hasen. "It's an unfair reading of the [Supreme Court's recent] decision." Wright agrees. "It's one thing to say that Congress failed to update the [preclearance] coverage formula, but it's something very different to say there's no record that would justify preclearance other than the record that existed in 1965."That is however, exactly what Texas is saying. The court will soon decide how seriously to take it.