“Mom, when Eric gets out of prison, can he come over and play?”

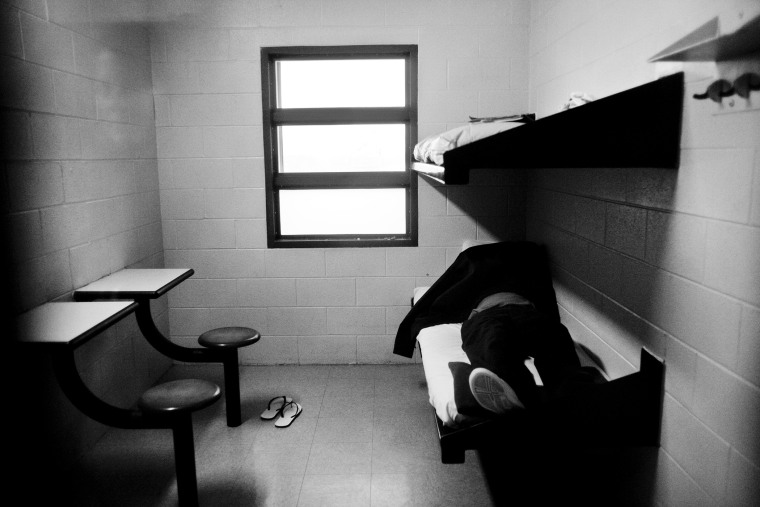

Stella, my 5-year-old daughter asked her question this summer as we walked by the razor-wire fences that separate a parking lot from the looming gothic maximum-security prison in Chester, Illinois. We were visiting Eric Anderson, who is serving a life sentence without parole there. I didn’t know how to answer – Eric’s sentence means he will never get out. He entered prison at 15.

"Nearly 100 people in Illinois are serving life-without-parole for crimes they committed before they turned 18."'

I started going to see Eric a couple of years ago with his mother, who has been visiting several times a month for 19 years. The Andersons have become friends, so taking my kids to meet Eric seemed natural. Days before our visit, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan and Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez filed a petition to the United States Supreme Court concerning another young “lifer:” Addolfo Davis. Davis and Anderson are two of nearly 100 people in Illinois serving life-without-parole for crimes they committed before they turned 18.

Both had been waiting for a resentencing hearing since June 2012, when the Supreme Court found mandatory life-without-parole sentences unconstitutional. However, the decision wasn’t clear about whether it applied to people already serving such sentences. The Illinois Supreme Court said it did —though now the state prosecutors are asking the US Supreme Court to reverse that decision.

Eric Anderson and his family are watching the Davis case closely, because if the highest court in the land rejects the appeal, he might have a chance to be re-sentenced to a term that envisions his eventual release.

Walking to meet Eric, Stella got right to the point. “Are they good guys or bad guys?” That is what everyone wants to know – is the court going to resentence someone to a shorter term, just for them to get out and continue being “a bad guy”?

There is no question that Eric Anderson did a bad thing, a truly reprehensible thing. With Nicholas Morfin, William Bigeck, Nicholas Liberto, and Edward Morfin, he was convicted of first-degree murder in the shooting deaths of Carrie Hovel and Helena Martin in what was described in court documents as a gang crime. The group planned to – and then did – shoot into a van that was marked as belonging to a rival gang. Bigeck and Edward Morfin were eligible for the death penalty because both were older than 18; each pleaded guilty in exchange for testimony against their codefendants and received 20-year sentences as a result. They are due to be released just months from now.

"Of youth sentenced to life-without-parole, nearly 60% are first-time offenders, never to be given a second chance."'

The crime Eric committed that night was his first offense. This is consistent with research by my colleagues at Human Rights Watch about youth sentenced to life-without-parole. Nearly 60% are first-time offenders, never to be given a second chance.

When we visit Eric, he spends time coloring animals for Stella, laughing at every little facial expression she makes. He teaches my 11-year-old son, Soren, the Anderson family handshake. Eric enthusiastically discusses books, offering up reading lists and hinting at spoilers.

In our conversations, he expresses deep gratitude for his mother’s devotion and for advocates, including victim family members, who seek to improve conditions for children in the adult criminal justice system. He is proud of his little sister, who just graduated from St. Mary’s College. He makes sarcastic (but loving) jokes about his father and brother, both of whom work in law enforcement.

He recently completed a program called “Thinking for a Change” with others who are serving long sentences, and is one of a handful of inmates at the facility who has a steady job, basically as an electrician. His mother says he has not been cited for a violation for about 10 years, because, as she puts it, “he’s grown up.”

"We have no way of knowing if those convicted of serious crimes as children are rehabilitated. Their sentence precludes them from ever being reviewed by anyone, anytime, until the day they die in prison."'

He consistently brings up wanting to be useful to kids who are prone to trouble and might not understand the consequences – he has been trying to find a community group that would bring at-risk boys to the prison to see what is waiting for them if they continue down a violent path.

Are they good guys or bad guys?

While my instinct tells me that Eric is not a bad guy, in Illinois, we have no way of knowing if those convicted of serious crimes as children are rehabilitated. Their sentence precludes them from ever being reviewed by anyone, anytime — from the age of 15, in Eric’s case, until the day they die in prison. What the state is saying is that nothing they do in all of that time matters.

Stella and Soren started school last week. Here is what I hope they learned at this unlikely summer school: With some notable exceptions, there is no such thing as a good or bad guy in perpetuity. Rehabilitation is possible. A community should recognize when people who once did something bad find a way to turn themselves around.

Maybe the U.S. Supreme Court will do the right thing, and by the time Stella finishes kindergarten, we can have Eric over to play.

Jobi Cates is senior director for development and global initiatives for the Midwest region at Human Rights Watch.