There is only one way to counteract the U.S. Justice Department’s aggressive intrusion into the Associated Press’s newsgathering operation, and that is with aggressive reporting.

News organizations across the country should unite to fight this unprecedented threat to the core of what journalists do: gather information to hold government accountable.

A cursory reading of the Justice Department’s guidelines on issuing subpoenas of reporters strongly suggests that officials might have ignored their own rules.

And that is a story—a big story.

Every news organization with a reporter in Washington should dispatch journalists to demand answers from the attorney general and the White House about who knew what, and when, in the authorization and execution of a subpoena that in all likelihood collected phone numbers of sources for every story—hundreds, if not more—that AP reporters were working on during a two-month period in 2012 in Washington, New York, Hartford and at the House of Representatives.

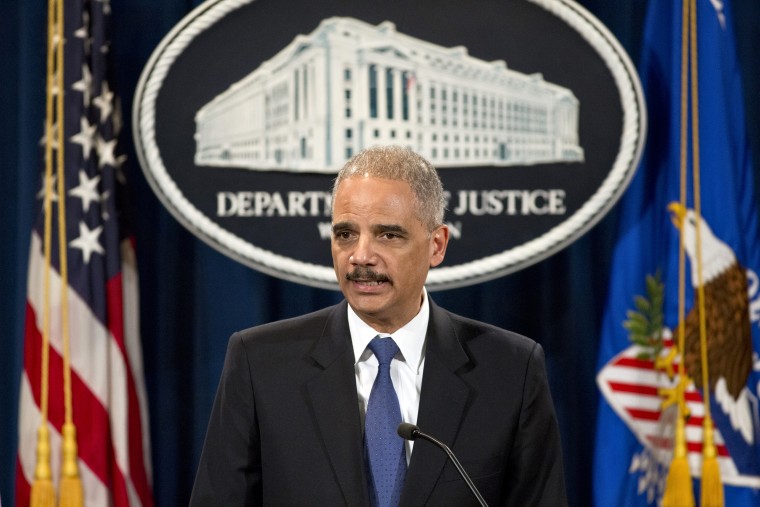

The AP’s president and CEO, Gary B. Pruitt, wrote a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder Jr. seething with rage. But it’s not enough. The AP should not be left to fight alone against this brazen infringement on freedom of the press.

Why? Because you could be next.

The technology exists for the government to track all of us, especially reporters and their sources. The AP presumably wouldn’t have known about the government’s intrusion if the Justice Department hadn’t revealed the subpoena’s existence.

Unfortunately, in recent years, journalists have fallen for the divide-and-conquer approach taken by government officials who sense weakness in the news business because of its struggle to profit in the digital era.

Lawyers for reporters cut deals with prosecutors in the Scooter Libby perjury case and with plaintiffs’ lawyers in the civil lawsuits filed by former Los Alamos scientist Wen Ho Lee, who was the subject of a misguided investigation into spying for China, and Dr. Steven Hatfill, the ex-U.S. Army scientist who was the target of a flawed FBI investigation into the deadly anthrax attacks in 2001.

Such shortsighted deals only serve to embolden government agents, prosecutors and plaintiffs’ attorneys into believing they can do whatever they want to journalists.

From August 2007 to February 2009, I resisted a federal judge’s threats to fine me into personal bankruptcy for refusing to identify sources who had provided information for stories I wrote about the FBI’s anthrax investigation.

In the Hatfill case, five reporters were ordered to disclose the names of their sources in August 2007. In a matter of months, I found myself alone, the target of a contempt-of-court motion in a hearing in a federal courtroom where I once covered the legal troubles of others.

I continue to wonder what would have happened if all of the subpoenaed reporters had banded together. Instead, our lawyers, the plaintiffs’ attorneys and the judge capitalized on our fears of being fined personally and sent to jail, and especially on our competitive natures to get us to race each other to obtain “waivers” of our promises of confidentiality from our sources.

They played us, and when I realized what was happening, I said, “Enough.” I refused to wheedle, cajole or trick sources into giving themselves up to protect me.

It is time to tell the Obama administration the same thing.

In the coming days, reporters should be relentless in figuring out whether the Justice Department followed its rules, 28 CFR 50.10, in obtaining and executing the AP subpoena.

Those rules begin with a poignant caution against abuse of power: “Because freedom of the press can be no broader than the freedom of reporters to investigate and report the news, the prosecutorial power of the government should not be used in such a way that it impairs a reporter’s responsibility to cover as broadly as possible controversial public issues.”

How the U.S. government deals with terrorism—from drones to waterboarding to foiling attacks—fits my definition of a controversial public issue.

The Justice Department’s rules also suggest that negotiations with the media should be attempted when a subpoena of phone records is considered, unless an assistant attorney general determines that such a discussion isn’t necessary or would jeopardize an investigation.

Did an assistant attorney general make that call? If so, which assistant attorney general? Why?

The attorney general is supposed to have final say on whether to subpoena a reporter to testify, or to demand phone records, according to the rules. Holder says he recused himself early on and turned over supervision of the leak investigation to the deputy attorney general.

Did the DAG, James M. Cole, know this was happening? When was he told? What was he told?

Until these questions are answered, reporters’ sources, often people seeking to reveal government waste and abuses of power, will continue to be sacrificed in the Obama administration’s overzealous pursuit of leaks.