CHICAGO — After burying her husband, Tracey Richardson took all her paintings off the walls.

She would have packed up the rest of her rental apartment, too, if she could afford her escape plan.

“After he died, I wanted a house real bad,” Richardson, 45, said. The kind of home they lived in when she and Lonnie were first married. Or the house her grandparents owned, where she stayed as a child when her mother couldn’t take care of her.

Richardson, however, is still trying to get there. She has a better job now, making about $19,000 a year working as a part-time assistant at her cousin’s dental office. She earns extra money styling hair on the side and has worked to improve her credit score, too. But a home of her own is still out of reach.

Before the housing crisis, lawmakers and lenders might have gone out of their way to help aspiring homeowners like Richardson. In the name of expanding affordable homeownership, banks made record numbers of loans, both good and bad, to lower-income Americans. In 2007 alone, more than 930,000 people earning less than $50,000 got mortgages, according to data from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. The subprime market spawned mortgages that didn’t even require borrowers to verify their incomes, and lenders deliberately targeted African-Americans and other minorities.

It’s now far more difficult for those from modest means -- or anyone with a less-than-pristine credit score -- to buy a home. And the barriers to homeownership are especially high in neighborhoods like Bronzeville, the African-American enclave on the South side of Chicago where Richardson lives.

The neighborhood is still dotted with the remnants of Bronzeville’s golden years: murals of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, who played in the local clubs and lounges; the stately greystone home of civil rights-activist Ida B. Wells. But that was also the time when blacks were restricted from buying property anywhere outside of select areas. Once the Supreme Court struck down such discriminatory laws in 1948, Bronzeville’s black middle class fled; Ida B. Wells became the namesake of the housing projects that took their place.

Now Richardson wants to get out, too -- and not just to another rental. “I just want to have my own land,” she says.

But lenders keep turning her away. “You need $20,000,” one bank told her. No, they couldn’t help her with a down payment. Good luck.

So Richardson has spent the past three years staying in the rental apartment where her husband died of a heart attack, at the age of 40 -- and where their eight-year-old daughter Faythe found his body.

Outside her door, the shootings have gotten so bad that Richardson insists that Faythe, now 11, spend part of every week with her grandparents in suburban Homewood. The Ida B. Wells Homes down the street from her apartment were torn down years ago, but the violence hasn’t stopped. “One day I was going to my mailbox," she says. "By the time I got back, someone got shot.”

She imagines owning a house where she can bring Faythe back home for good, take up painting again, and host her three grown children from her previous marriage. "So I could have dinner. Family dinner," she says.

***

Black and Hispanic homeowners suffered disproportionate losses in the 2008 housing crisis, as predatory lending wiped out what few assets they had. But in the midst of the recovery, they’re dealing with a second crisis: The fear of another housing bubble could now keep them from getting a loan.

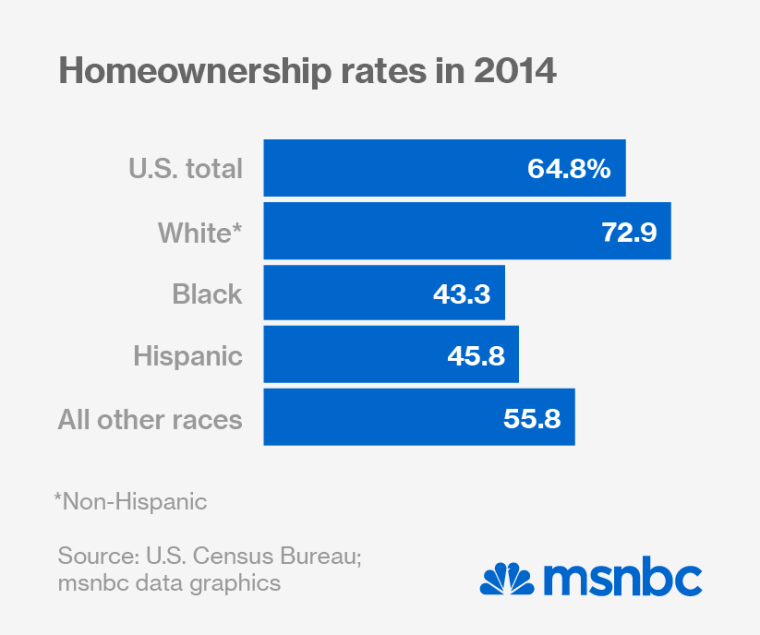

Forty-three percent of African-Americans now own their own homes, according to the Census Bureau, down from 49% in 2004; it’s now at the lowest level since 1995. Among Hispanics, it’s 46%. By comparison, more than 73% of white Americans are currently homeowners. While the worst mortgage practices are now banned, all kinds of other credit has evaporated as well, depressing homeownership rates even further among minority Americans.

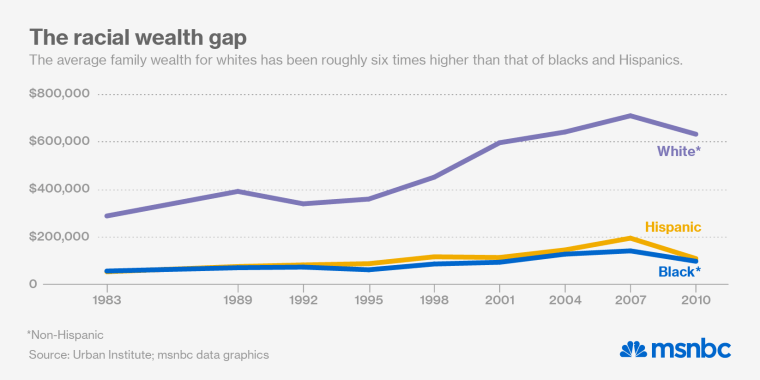

That’s a big reason why the racial wealth gap has grown so large. By 2010, whites had six times the average wealth of blacks and Hispanics, according to the Urban Institute—far greater than the 2:1 income gap between the groups. The Pew Research Group, drawing on different data, estimates that the median white household has twenty times the wealth of a black household.

No one wants a return of the lending abuses that help drive the crash. But such stark inequities have also raised new questions about whether the government should try again to expand homeownership to build wealth among lower-income and minority Americans—or whether real estate investments are a risky bet that will only backfire once more.

It’s a debate that cuts to the heart of what it means to be successful in America.

Even after the crash, most Americans continue to sanctify homeownership. According to one 2013 survey, 76% believe that being able to own your own home is necessary to be considered middle class. And they're hearing the same from the highest rungs of government: In a speech last August, President Obama glorified homeownership as “the most tangible cornerstone that lies at the heart of the American Dream, at the heart of middle-class life.” He said later: "A home is the ultimate evidence that here in America, hard work pays off, that responsibility is rewarded."

***

A young black woman breaks down in tears on camera.

“It is possible—I am going to be a new homeowner!” she said.

It’s part of the traveling roadshow from the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America, a non-profit that recently set up camp in Chicago’s sprawling Hyatt Regency. When representatives came to Capitol Hill in May, a woman rose to the podium to explain how a NACA loan made her family’s wealth skyrocket. “I was blessed to have my house almost triple in value in almost five years,” she said. “We’ve been praying for this for a long time. And today is the day!” an older black woman says proudly on the same video as it played before a group of aspiring Chicago homeowners.

NACA prides itself on offering mortgages to lower-income borrowers squeezed out of the market after the recession: No credit score minimums, no down payments, and no abusive interest rates, courtesy of agreements that the group has struck with big lenders. The tradeoff: mandatory workshops, counseling, two years of income returns, volunteer hours for the group, and voter registration.

“You’ll be insane to walk away from the deal we’re going to give you,” NACA loan officer Jim Spigutz, said. “Whatever your income is, there is a house for you,” he added later.

Still, participants are warned that it will take until at least October to obtain one of their mortgages, even if they qualify, given the high demand.

Richardson, who’s seeking outside assistance to receive a loan, is wary; she’s heard such promises before. “They’re not designed to help you for real—they’re designed for people inside the program to make money,” she said.

Like many Americans, she’s become skeptical of anyone promising a mortgage that sounds too good to be true. She points out that her mother-in-law, who works in real estate, is still struggling after losing multiple properties in the housing meltdown.

“I need to be taught how to purchase a home without being ripped off,” Richardson says.

She has good reason to be cautious. In Chicago, officials are still going after lenders who exploited minority borrowers in the run-up to the crash.

Just three months ago, Cook County sued Bank of America and HSBC for causing “tremendous tangible and intangible damage, particularly to African American and Latino communities” through its predatory lending practices, intensifying the city’s urban blight.

New mortgage regulations are only beginning to take hold: The 2010 Wall Street reform law cracks down on abusive mortgage products, limits highly leveraged loans, and requires lenders to verify borrowers’ ability to repay loans—or else face a potential lawsuit. But the biggest reforms just started taking effect in January, more than five years after the financial meltdown.

It’s not all that's changed in the mortgage market. In the rush to prevent another housing bubble, Washington also reversed course on decades of policies explicitly aimed at helping lower-income and minority Americans buy homes.

"I feel like I should have a piece of land for my family and my children’s children. For them to say, ‘This is what my momma worked hard for.'"'

President Clinton allowed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—which purchase loans and resell them to investors—to use subprime securities to meet affordable housing goals. His successor, President George W. Bush, went even further to promote “the ownership society,” lobbying for major homeownership subsidies and government-insured mortgages that required no down payment.

Such enthusiasm has since evaporated. Under the leadership of Edward DeMarco—the Bush-appointed head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency who left office in January—Fannie and Freddie have toughened up their mortgage underwriting standards and imposed higher fees. Federal officials have also pushed lenders to buy back government-guaranteed loans that defaulted, saying the banks deliberately misled Fannie and Freddie about the quality of the mortgages.

The strategy has stabilized the housing giants' finances, but it's also made banks more reluctant to lend. Mortgages to those with less than perfect credit or limited incomes have all but disappeared. Subprime loans—which go to borrowers with a weak credit history, typically a sub-620 credit rating—made up just 0.3% of new home loans in October, according to research firm CoreLogic. The average credit score for FHA loans jumped from 640 to 693 in the past five years, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies—far higher than the 580 minimum on the books.

Some housing experts fear that in cracking down on easy lending, we’ve discarded the good with the bad.

It’s a mistake to assume that homeownership itself fueled the crisis, argues Janneke Ratcliffe, executive director of the University of North Carolina’s Center for Community Capital. She points out that the U.S. homeownership rate actually peaked in 2004, years before the mortgage meltdown. Then the subprime industry took advantage of Washington’s push for homeownership to convince the government to open to door to more dubious loans. "In the name of homeownership, certain players were able to get a lot of regulatory bypass—wolf in sheep’s clothing," says Ratcliffe.

But most predatory lenders weren't even targeting new homebuyers, she says. Just 38% of subprime loans between 1998 and 2006 went towards new home purchases, and only an estimated 9% were given to first-time homebuyers, according to a study from the Center for Responsible Lending; the rest were refinanced loans.

That distinction was lost in the aftermath of the crisis. “We have to be really careful in distinguishing the risk of certain people and the risk of certain lending products,” she says.

Ratcliffe and others believe that even those with low incomes and weaker credit scores can become responsible homeowners if they select a home they can afford and receive plain-vanilla mortgages. “The trick is to expand the credit box without excessively expanding the risk,” Ratcliffe says. In her view, homeownership could benefit lower-income Americans in particular by turning their home into a savings vehicle and stabilizing their housing costs.

Not everyone agrees. In academic and policy circles, there’s a growing chorus of experts who argue that homeownership was oversold to begin with—and that it’s still an exceptionally risky idea for lower-income borrowers.

Princeton economist Atif Mian believes that even conventional mortgages force homeowners to take on too much risk. The notion that cheaper lending can be a shortcut to wealth is misguided, says Mian, co-author of “House of Debt,” a new book on the causes of the Great Recession.

“In terms of [expanding] homeownership—including to low income and minorities—we had the most aggressive experiment we could think of in the 2000s," he says. "The consequences were what they were." The Great Recession entirely wiped out all of the gains in net worth that Americans had made between 1992 and 2007, he estimates.

Even without predatory loans, Mian continues, most U.S. mortgages are structured to make them inherently risky for lower-income borrowers if their home value plunges, while the bank is left off the hook. As a result, the most straightforward mortgage arrangements can destroy a family’s finances if home values plummet, and the impact is even more devastating for borrowers with few other assets.

"This is the fundamental feature of debt: it imposes enormous losses on exactly the households that have the least,” Mian and his co-author Amir Sufi write in their book. And it's the entire economy that suffers as a result. “The most severe recessions in history were preceded by a sharp rise in household debt and a collapse in asset prices” as households cut back on spending, the authors conclude.

"The reality is that most of the time, it is a good investment. "'

Others point out that homeownership isn’t generally a great investment for individuals to begin with: In the long run, its returns are barely more than zero against inflation, significantly less than the stock market. They argue that many Americans would be better off putting their savings elsewhere rather than tie it all up in a down payment if they’re looking to build wealth long term.

But you can’t live inside a stock portfolio. And many lower-income families still view homeownership as the only available vehicle to building wealth, particularly as the cost of rental housing continues to rise across the country.

Even those who suffered the most during the mortgage meltdown haven’t given up on the notion that owning a home is a smart move.

During the housing bubble, Joel Salgado, 44, bought not one but two apartments as a first-time homebuyer, naming the properties after his young sons, Joel Jr. and Joshua. Then in 2009, the Chicago steel factory where he worked as a project manager went out of business. He lost both apartments and declared bankruptcy.

Salgado says he and his wife have become more financially savvy since the meltdown; with his income dropping from $100,000 in his best pre-recession years to his current salary of $55,000 at a non-profit, they’ve had little choice. “If we don’t need it, we don’t buy it,” he says.

But he still sees getting back into the housing market as a necessity for his family, hoping to send his sons to better public schools.

“The reality is that most of the time, it is a good investment,” he says.

***

For Richardson, owning a home isn’t simply an investment; it’s also a question of justice.

Her grandfather was a steelworker and a Navy veteran, but he had to bring in his own lawyer before he was able to buy a home in Fernwood, a neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. It was 1968, the year that the federal government finally outlawed redlining—the discriminatory housing practice that turned Chicago into one of America's most segregated cities.

He wasn’t the first to fight to live there. When black veterans moved to the neighborhood in 1947, “gangs of whites yanked blacks off streetcars and beat them,” writes The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Richardson now wants to own the home her ancestors were denied.

“We need land—we need to own something. I think it’s only fair. Forty acres and a mule—where is it?” says Richardson, whose father’s family descended from former slaves who migrated north from Mississippi. “I feel like I should have a piece of land for my family and my children’s children. For them to say, ‘This is what my momma worked hard for.”

Every week, housing advocates make the case that owning a home will not only help families like Richardson’s, but also elevate communities that have yet to recover from decades of racist policies designed to trap minority residents in crumbling ghettos.

On the west side of Chicago, more aspiring homeowners have been showing up at the Spanish Coalition for Housing, which was originally formed in 1966 to combat redlining.

“You’re going to be helping your future, your family’s future, the future of your neighborhood,” housing counselor Madeline Morales told Richardson and others at a recent workshop. “You’re going to increase the economy of your neighborhood.”

Still dressed in her dental-office scrubs, Richardson listened as Morales described some of the public programs designed to help lower-income homebuyers, including “Welcome Home Illinois,” a state-funded program that offers $7,500 down payment assistance and below-market interest rates. But Morales warned funds for such help are limited. “It’s running out fast,” she explained.

While federal lawmakers are focused on preventing another housing bubble, a vocal group led by the Congressional Black and Hispanic caucuses worry that Washington is abandoning aspiring minority homeowners who still face unfair racial barriers to securing a loan. An Urban Institute study, for example, found African-Americans and Hispanics were far more likely to be rejected than white and Asian applicants with similar credit scores in 2012.

For Mitria Wilson, it's just a modern-day version of what happened after World War II, when the government's VA home loan program drove up white homeownership rates while racist loan officers shut qualified minorities out.

“Homeownership has been the mechanism by which the U.S. has created a middle class. The ownership for white Americans is more than 70%,” says Wilson, advocacy director at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. “Then all of a sudden, when you talk about it being expanded to working class Americans, or communities of color, we say it’s not all that it’s cracked up to be.”

On Capitol Hill in May, she put it more succinctly: “We’re talking about not letting brown people have access to wealth.”

***

It’s not just individual families whose fates are at stake. The younger generation is more racially diverse, so minorities will make up an increasingly large pool of potential first-time homebuyers in the U.S.

“The whole economy’s fate will be affected by how well we reverse the homeownership gap,” Mike Calhoun, executive director of the Center for Responsible Lending said on a recent panel. “To move this whole market, we’ve got to open up the credit box.”

Even as banks begin edging back into subprime lending, the private market alone is unlikely to take on risks without imposing high interest rates and steep down payments. One North Carolina credit union made low-interest loans to borrowers of limited means—successfully helping many build wealth over time—but only after receiving a $50 million grant from the Ford Foundation to absorb potential defaults.

"There is no doubt that people with lower incomes and less wealth are higher risk. There has to be some high compensation for that risk," says Chris Herbert, research director of Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies. Mian, the Princeton economist, wants to see lenders take on more of the downside risk when home values drop—perhaps in exchange for a share of the home’s appreciation. But few banks are eager to such radical reforms yet.

Given such realities, housing advocates insist it's the government's responsibility to help subsidize mortgages for Americans on the margins of the housing market. “If the government going to provide a guarantee for mortgages, there’s got to be a duty to serve folks who would otherwise be passed over,” says former Democratic Rep. Brad Miller, who helped write the new laws regulating abusive mortgages.

Under pressure from Democrats and outside advocates, lawmakers have recently hinted they might go further to subsidize lower-income home ownership, particularly as most private lenders remain reluctant to loosen up credit.

That might mean more down-payment assistance, lower fees for future borrowers, or new programs like one launched by the Federal Housing Administration that reduces premiums if homebuyers get credit counseling. But the administration can only take limited steps without broader action from a reluctant Congress.

Having bailed out Fannie and Freddie during the crisis, lawmakers are now trying to wind down the housing giants—whom Republicans blame for the entire meltdown—and replace them with more limited government mortgage insurance. But prominent liberal Democrats and housing advocates are already worried that proposed reforms won’t do enough to guarantee a commitment to affordable homeownership.

By contrast, the government continues to hand out more than $70 billion a year in tax breaks to higher-income homeowners: More than three-quarters of the taxpayers who benefit from the mortgage interest deduction earn more than $100,000 a year, according to the Center on Budget and Policies Priorities.

The Resurrection Project’s Kristen Komara believes the real problem is more fundamental. Without a steady job at a decent wage, individuals won’t be able to pay back loans even with generous outside assistance. And the same racial disparities persist in the labor market. Black Americans with an unemployment rate that is consistently twice that of whites, and the gap is even bigger in major cities like Chicago.

“Incomes just aren’t rising, they are not keeping up with the housing market,” says Komara, vice president of financial wellness at the community-development organization. “I have a lot of folks who ask, ‘Can I get a brand-new rehabbed house for $60,000?’ Nowhere is that possible.”

***

Richardson still isn’t sure where the money for a home will come from. She’s planning to pay down her outstanding debts to help raise her credit score, which is currently hovering near 600. Her 25-year-old son, Namiah, keeps telling her that he’ll help her out. “Mom, I’m going to give you money,” he tells her. But despite working two jobs and holding a college degree in finance, he doesn’t have the cash yet either.

Ultimately, she says, “I’m depending on no one but me and God.” And she knows where she wants to live, in her dreams at least.

The other week, she went to walk around Oak Park, a middle-class community just west of Chicago. Unlike the surrounding areas, where discriminatory housing policies created long-standing pockets of segregation, Oak Park passed a pioneering 1968 fair housing ordinance to insure equal access to housing.

“Big trees, lots of greenery. It smells so good,” she says. She remembers being struck by the sight of two teenagers sitting on a bench.

“It was a white girl and a black girl, sitting there, having a good conversation, laughing. They had their music on,” she recalls. “I thought it was so nice to see that.”