World leaders who gathered in Paris this week to negotiate a climate deal described it as one of the most important meetings in human history -- a prerequisite to staving off a catastrophic rise in global temperatures.

Then there are the Republican candidates looking to succeed President Obama, who have greeted the COP21 event with a mix of yawns and jeers. In Washington, GOP congressional leaders are working to derail the Paris plan to curb emissions and are even warning foreign leaders not to trust Obama’s promises.

Scientists, politicians and citizens around the world are coalescing in favor of international action. While the exact consequences of failure are unknown, the overwhelming consensus among scientific researchers is that the carbon emissions warming the planet could cause an array of effects from droughts to rising sea levels if left unchecked.

“Never have the stakes been so high because this is about the future of the planet, the future of life,” French President Francois Hollande said on the conference’s opening day.

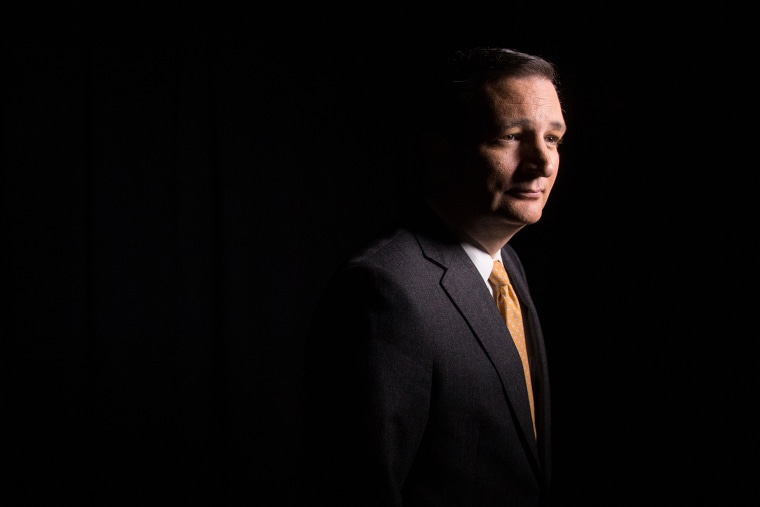

The Republican Party, meanwhile, has largely moved in the opposite direction. After a brief GOP flirtation with environmentalism in the 2000s, the entire top tier of the 2016 presidential field is skeptical of efforts to address carbon emissions or outright hostile to the science driving the issue. This includes candidates with relatively mainstream credentials like former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, Ohio Gov. John Kasich, and Florida Sen. Marco Rubio as well as more untraditional contenders like Donald Trump, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Dr. Ben Carson.

Bush, who has questioned the extent to which human behavior causes climate change, repeatedly lambasted the Paris talks this week on the campaign trail.

“I’m not sure I would have gone to the climate summit if I was president today,” he told reporters on Tuesday, citing potential economic dangers to restricting carbon emissions.

At an Iowa town hall, Bush said he feared threats to the nation’s “sovereignty” from a climate deal, while cautioning he still had not seen the final product of the conference. The Bush campaign emailed the press a radio appearance in which he criticized Obama for, in the candidate’s view, putting climate ahead of the economy and terrorism.

Rubio, who has long questioned climate science, has performed a similar dance. On Fox News Monday, Rubio argued there’s no scientific “consensus” on the issue. At the same time, he said that even if the science is correct, it’s futile for the U.S. to cap emissions given that it would take a global effort with countries like China to make a serious impact. “America is not a planet," he said at a GOP primary debate in September.

That sounds an awful lot like an argument in favor of the Paris talks, but Rubio’s not a fan of them either and has told supporters they will have “no meaningful effect on climate change.”

Kasich has said he “[doesn't] believe that humans are the primary cause of climate change.” New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said on MSNBC’s "Morning Joe" Tuesday that climate change “is not a crisis” based on his gut instinct.

Among other GOP candidates, opposition is even stronger. Trump has claimed that climate science is a hoax and said on Tuesday it was “ridiculous” for Obama to worry about the issue. Cruz has mocked climate science as a “religion” and said in Iowa Tuesday that Obama “apparently thinks having an SUV in your driveway is more dangerous than a bunch of terrorists trying to blow up the world.”

The three Democratic presidential hopefuls, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley, are lined up behind Obama’s efforts to tackle climate change and have pledged to continue efforts to lower emissions if elected. The stark contrast makes climate one of many issues where the presidential election could have a lasting impact on policy for years to come.

How much of an impact is not entirely clear. For now, Obama can veto challenges from congressional Republicans to his proposals. Even if a Republican is elected to succeed Obama and has control of Congress and more power to shift policy gears, he or she might be constrained by existing regulations, court cases, and international commitments from going too far.

The diplomatic pressure alone to maintain America’s commitment to reduce emissions by 26-28% from 2005 levels would be enormous. Republican candidates, from Bush to Cruz, frequently complain that Obama has alienated America’s allies. That’s a difficult case to make while also threatening to thwart a massive global effort to address an issue America’s allies have named as a top priority.

“It’s easy to cry when you’re standing on the outside, but when you’re sitting in the Oval Office and you have 100 nations around the world who want you to live up to the agreements and you’re looking at the evidence of what’s happening, its going to be harder to walk away,” Sharon Burke, a senior advisor to the New America Foundation, told msnbc.

Even in the context of center-right politics around the world, U.S. Republicans are considered global outliers – one study found they were unusual among conservative parties in nine developed nations in their opposition to climate action. German leader Angela Merkel has earned the moniker “the climate chancellor” and said the issue is “a question of the future of mankind,” while British Prime Minister David Cameron told the Paris conference that he refused to tell his grandchildren he failed to take action.

In Asia, leaders are looking to the U.S. for reassurances that they’ll provide aid to help transition to renewable energy and use their leverage to pressure China – with whom Obama negotiated a major bilateral deal on emissions – to participate in a meaningful way. Some GOP candidates have singled out the impact of pollution from China and India as reason to avoid unilateral regulations, but they haven't laid out prescriptions to pressure them into a collective solution.

Burke said she was optimistic that candidates like Bush and Rubio, even after pledging to reverse Obama’s regulations, would not derail climate commitments made in Paris. “I see a lot of wiggle room in their statements,” Burke said. More committed anti-science candidates like Trump are another story, however.

Kathy Sierra, a Brookings Institute fellow who researches climate policy, identified a number of domestic obstacles Republicans would face in undoing Obama’s climate action as well.

The EPA is racing to finalize regulations that form the core of the president’s Clean Power Plan, which will make them more difficult to reverse. The Supreme Court has ruled that the agency is legally required to address carbon emissions and a GOP administration would have to submit new regulations or prove that greenhouse gases not harmful. Finally, the private sector is already undertaking expensive investments to limit energy use in response to anticipated regulation, and would be unlikely to backtrack on at this point.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t risks. Sierra warned that by tossing out Obama’s plan and starting from scratch, a GOP president could slow things down with a lengthy review process, legal battles, or legislative debates.

“They could say we're going to consider this a lot longer while the emission targets under the Obama plan are really predicated on a pretty hard drive,” Sierra said.

The trickiest part might be getting on board with U.S. commitments to aid developing nations. Currently, Republicans in Congress are threatening to block $3 billion for a UN climate fund. Even then there’s some possibility other actors could step in to fill the gap: Burke cited this week’s multi-billion dollar pledge by Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos and other elites to invest in energy research as an example.

As it stands, the organizers of the Paris conference already have made some concessions to political reality to give talks a better chance to succeed. Unlike previous global attempts to tackle the issue, the Paris talks rely on commitments from nations instead of a binding treaty that would require a two-thirds majority to pass the Senate and likely fail even with Democrats in control.

When it comes to the politics of 2016, it’s unclear what role the issue will play.

Former White House adviser John Podesta, now a top Clinton adviser, has predicted Republicans will pay a price with voters for appearing backwards on climate. A New York Times/CBS poll this week found two-thirds of respondents favored joining an international agreement to tackle the issue. In the same survey, Republican voters were more divided than their leadership suggested – a slight majority opposed an agreement but favored regulations to limit power plant emissions.

That said, translating support for action on climate into votes could be tricky. Billionaire Tom Steyer spent $74 million targeting Republican candidates through his group NextGen Climate in the 2014 midterms with limited results, but it’s possible the general election environment will be more favorable for such an appeal. Democrats certainly sound eager to give it another shot.

“[T]he Republican deniers, defeatists and obstructionists should know—their cynical efforts will fail,” Clinton wrote in a Time op-ed on this week.