Defenders of Stand Your Ground laws and other efforts to expand gun rights have for years invoked female victims to justify them. The scenario of a woman shooting a rapist as a rationale for broader gun rights is a recurring one, particularly since the killings of Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis in Florida have cast Stand Your Ground laws in particular in a harsh light.

“Calls to repeal ‘Stand Your Ground’ are anti-woman. Imposing a duty-to-flee places the safety of the rapist above a woman’s own life,” wrote a pair of Florida lawmakers in 2012. Or as NRA President Wayne LaPierre has explained it, “The one thing a violent rapist deserves to face is a good woman with a gun.”

But as Marissa Alexander faces a possible 60-year sentence in Florida for what she called a warning shot fired against her abusive husband -- and on Friday filed a request for a new Stand Your Ground immunity hearing -- it’s clear the definition of “a good woman with a gun” doesn’t necessarily apply to everyone. And according to a new analysis of FBI homicide data, race plays a disproportionate role.

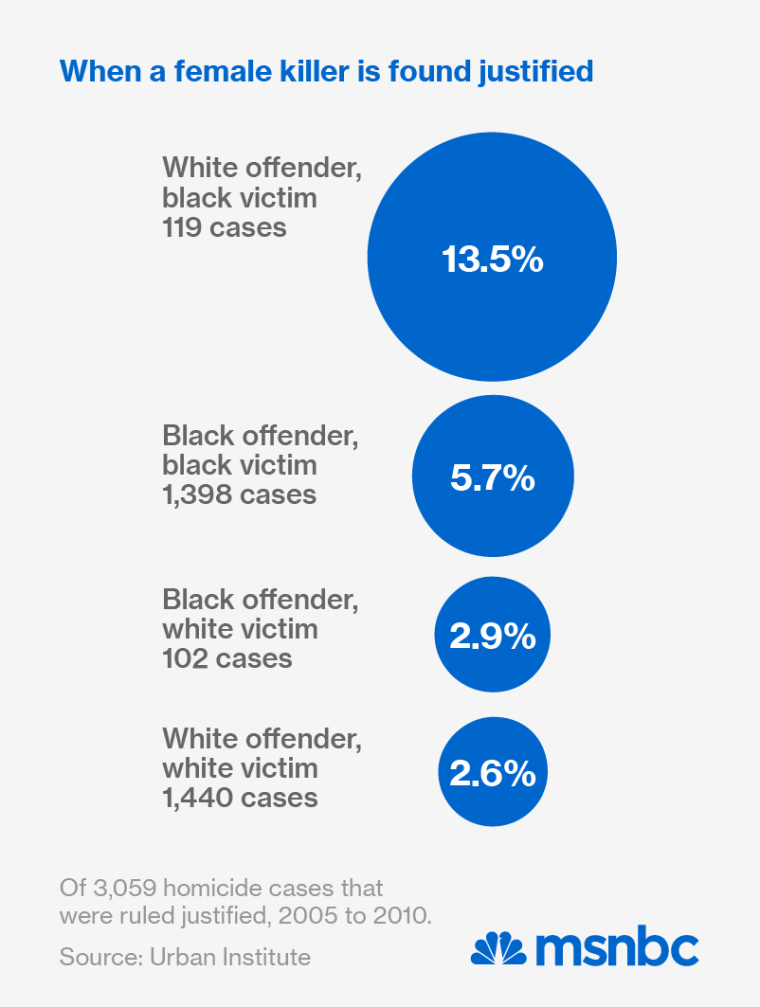

The analysis was prepared by the Urban Institute at msnbc’s request. It used national data on homicide cases that were found “justifiable” – generally, those in which no charges were brought, on the grounds that deadly force was appropriate.

Among cases nationwide where a woman killed an adult man, white women who killed black men were most likely to be found justified, at 13.5% of the cases, the data found. By contrast, just 2.6% of white women who killed white men, and 5.7% of black women who killed black men were found to be justified. (Most killings happen between people of the same race.)

“In any situation where a black male is perceived as being the aggressor, you are much more likely to have the homicide considered justifiable,” said John Roman, senior fellow at the Urban Institute, who analyzed the data for msnbc. “If they’re involved in a homicide, the finding is likely going to go against them.”

Among homicides overall (perpetrated by both men and women), Roman previously found that 11.4% of murders of black people committed by white people were found justified, compared to 1.2% of black-on-white murders. The disparity is widest in states with Stand Your Ground statutes.

No one was hurt in the Alexander incident, where the charge is three counts of aggravated assault. But the most detailed data available is on homicide charges. The FBI also chose to exclude data from Florida, where all three high-profile Stand Your Ground cases have originated.

A project by the Tampa Bay Times in Florida offers some clues about how the laws are applied there. A database the newspaper compiled of cases in which Stand Your Ground played a role showed eight in which a female killer was found justified and six where she was not. All the cases where a woman did not succeed in claiming self-defense, including several in which she said she was the victim of rape or other physical abuse, involved white males.

By contrast, among the eight murder cases found justified, half involved women killing black men. Those cases included both intimate partner and stranger violence.

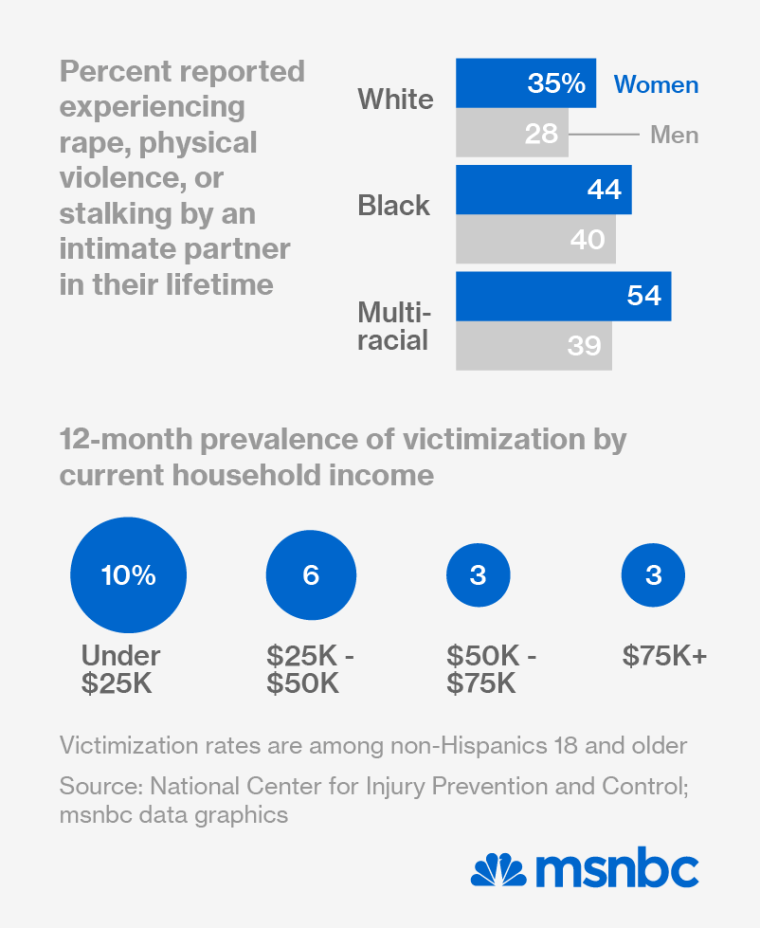

Women are still far more likely to be killed by their intimate partners than the other way around. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Females made up 70% of victims killed by an intimate partner in 2007, a proportion that has changed very little since 1993.” In fact, the share of female deaths due to domestic violence has actually grown by five percentage points in that time, even as homicides – and crime in general – declined.

The presence of a gun in a house more often means that it will be turned on the woman. One study found that living in a home with a gun made women three times more likely to be killed there. Another found that "the risk connected to gun ownership increases to 8-fold when the offender is an intimate partner or relative of the victim and is 20 times higher when previous domestic violence exists."

Experts on intimate partner violence say women in such situations have faced an uphill battle in convincing prosecutors and juries that they were victims acting in self-defense.

“I find myself saying often, the sad thing is that the only correct woman in a self-defense case is a dead one,” said Sue Osthoff, director for the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women.

A key question in any self-defense case is whether the defendant had a “duty to retreat” – that is, whether they were required to run away, “go to the wall” or otherwise defuse the situation before using deadly force, if at all possible. A broad exception, codified in most states, is the so-called castle doctrine, which holds that there is no duty to retreat in one’s own home.

The castle doctrine had its origins in a patriarchal figure defending his terrain from an outside aggressor. The idea that the home could itself be a place where violence originated – perpetrated by and against its inhabitants -- came later, through feminist jurisprudence.

Eventually, some courts began applying the castle doctrine to domestic violence situations where a victim acted in self-defense, though it was complicated when, as is often the case, both parties had a legal right to be in the house. In 1997, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the castle doctrine applied in such situations, because “a person in her own home has already retreated ‘to the wall’ as there is no place where she can further flee in safety.”

That same year, the New Jersey Supreme Court criticized that state’s self-defense laws for not covering a woman who shot her abusive husband, and New Jersey promptly changed its law.

In 2005, Florida became the first state to expand the castle doctrine to include anywhere the threatened person had a right to be -- such as a public sidewalk. Florida also created a presumption that deadly force was justifiable when someone was defending against an unlawful forceful entry into their home or vehicle. At least 22 states followed suit.

Some news outlets have erroneously reported that there is a domestic violence exception to Florida’s Stand Your Ground statute. That’s not the case. But there is a higher burden for cases involving people who live together. The presumption that deadly force was justified doesn’t apply when the attacker is a cohabitant, unless the one who used deadly force had a domestic violence protection order against the attacker. But that doesn’t mean a domestic violence victim who acted in self-defense can’t subsequently qualify for immunity at a Stand Your Ground hearing.

Stand Your Ground laws have met with mixed reviews from advocates for women in abusive situations.

“I do not think that Stand Your Ground benefits women facing intimate partner violence in any way that they wouldn’t have had under the prior law,” said Donna Coker, an expert on domestic violence law at the University of Miami Law School. “And I think it increases the risk to a significant number of people.”

Others were not prepared to dismiss the laws entirely. "SYG laws, when applied properly, can eliminate one of the many barriers a battered women defendant who acts in self-defense faces," wrote Cindene Pezzell, Legal Coordinator for the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women, in 2012.

Pezzell urged opponents of Stand Your Ground to "carefully consider whether it is the SYG laws they find objectionable, or whether it is the application of those laws that is problematic."

Because self-defense cases rely so much on subjective assessments of what is reasonable to fear, they are particularly vulnerable to bias. In Alexander’s case, prosecutor Angela Corey – who could have dropped the charges or pursued lesser ones -- has repeatedly insisted that Alexander “was angry” when she fired the shot, rather than “in fear.” That’s despite the fact that Alexander’s husband, Rico Gray, had been arrested twice on domestic battery charges and Alexander had a protection order against him; that he admitted in a deposition to domestic abuse (an admission he later retracted); that the events took place a few days after Alexander gave birth prematurely; and that, according to Alexander, Gray threatened to kill her that day.

“You tell me that I can bear arms. You tell me that I can go to class and get a permit [to carry],” Alexander told Loop21, an African-American issues site. “And you tell me everything that I need to do to get on the right side of the law, which also includes getting an injunction for no violence in place. And then you try to dictate to me my level of fear.”

Said Mary Anne Franks, a professor of University of Miami School of Law, “There’s this idea that anger and fear are mutually exclusive. Black women are not allowed to get mad about the fact that someone is allowed to beat them.”

Franks wondered if the same standard had been applied to Michael Dunn, the white Florida man who shot into a carful of black teenagers in 2012, killing Jordan Davis.

“Was Michael Dunn scared, or was he angry?” Franks said.

If a woman stays with or maintains contact with an abusive partner – whether it’s because she is dependent on him, because they have children, because she loves him, or any other reason short of outright imprisonment – a jury may also be skeptical of her victim status.

“Legally, whether a woman is in an abusive relationship or chooses to stay in one, or whether she could have left when the violence started, is irrelevant to a self-defense claim,” Osthoff said.

And leaving an abusive partner might not be enough, anyway. “One of the primary misconceptions is that many people believe if she leaves the relationship, she will be safe,” said Coker.

Among inter-spousal homicides, most men who kill women do so after separation, Coker said. For women, she said, it’s the other way around.

“It was a deterrent, and thank God it actually worked,” Alexander told Loop21 of firing the warning shot. “Had it not, we would have had another statistic. And that would have been me being dead.”

An appeals court ordered a new trial for Alexander last year, saying the jury instructions improperly put the burden on her to prove she was acting in self defense.

Corey has subsequently sought three consecutive, instead of concurrent, sentences for Alexander, which would total 60 years. Florida has mandatory minimum sentencing when a gun is used in the course of committing a felony.

Aleta Alston-Toure of Free Marissa Now has said the new sentence would “be a decisive blow” to the right to self defense for black women and all women.

Incarcerating Marissa Alexander, she said, “will send a strong message to all survivors that violence against them will be ignored and they instead will be subject to prosecution if they defend their lives.”