EUREKA, Calif. – It did not look particularly like a history-making day in the Redwoods. The jars of condoms and the pinned-up primer on the HPV vaccine at the Six Rivers Planned Parenthood were undisturbed, and the waiting room was no more taxed than any other Saturday. The usual lone protester, loosely referred to as “the pastor,” had come early, before the clinic even opened, and gone home.

But inside the employee kitchen, there was proof of something special about this January morning, days after the anniversary of Roe v. Wade. “Well-behaved women rarely make history,” read a note affixed to some irises. “Today we make history!!!” Another card thanked one nurse practitioner by name for “blazing the trail.”

Thanks to a law passed last year, California is actually adding abortion providers – nearly fifty nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and physicians’ assistants, trained to provide aspiration abortions in the first trimester –with more to come.

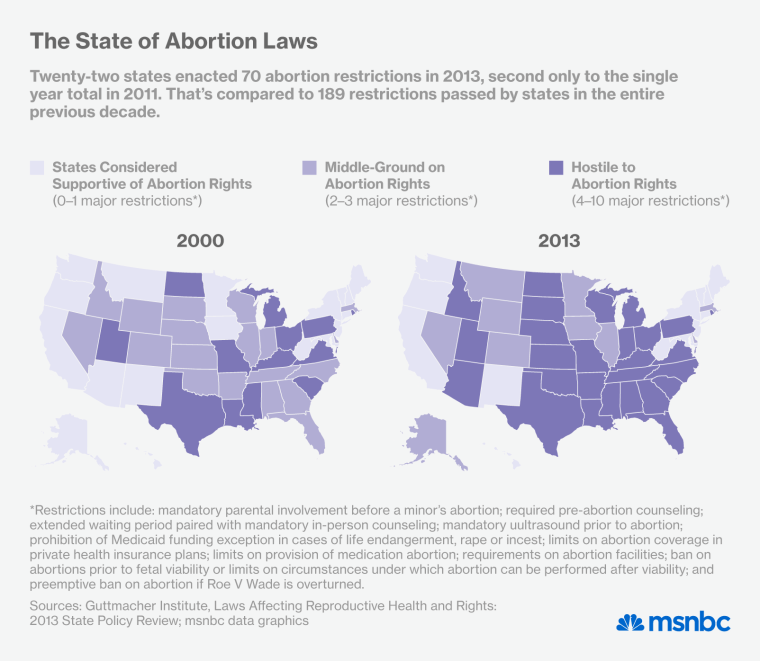

The state is bucking a nationwide trend as a wave of new restrictions is forcing abortion providers across the country to shut their doors. In Texas, the second-largest state after California, initial enforcement of a law passed last year initially put a third of the clinics of the state out of commission, and when new regulations go into effect in September, all but a half-dozen clinics are expected to close.

Meanwhile, in California, a Eureka nurse practitioner -- who worried about the safety of being named in the press -- had just officially become one of the new providers of vaccuum aspiration abortion, the most common procedure.

“I am used to being in a place where we are talking about all the options for birth control and for pregnancy,” she said simply. “It was just a no-brainer, a logical next step.”

The fact that it was an ordinary day – boring, even – was the whole point. The most radical move of all wasn’t just passing a law to expand abortion access. It was treating the termination of a pregnancy like any other medical procedure, and seeing if that changed women’s lives.

…

“I don’t really see the need for this bill here,” said Assemblyman Don Wagner, an Orange County Republican, at a committee hearing last April for AB154, which would eventually make the nurse practitioner’s day possible. He wondered why there were no women testifying that they had been unable to access an abortion.

“Where is the evidence that there are underserved populations out there?” Wagner asked.

"California is one of the few states whose reproductive health laws are based on science."'

Evidence was something of a magic word to Tracy Weitz, testifying that day in her capacity as a medical sociologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Weitz had overseen a massive peer-reviewed study, published in the American Journal of Public Health, that had trained the Eureka nurse practitioner and dozens of other advanced-practice clinicians on providing aspiration abortions. Armed with a waiver from the state, the study set out to determine whether such clinicians could provide early aspiration abortions as safely as physicians. Eleven thousand abortions later, there was no meaningful difference.

Weitz doesn’t perform abortions, but her colleagues at San Francisco General Hospital do, and they specialize in later ones. And over the years, they’d noticed something.

“We were serving an extraordinarily high number of women later in gestation who were coming from throughout California,” Weitz told Wagner.

The later in pregnancy an abortion occurs, the more expensive it is. And though abortion remains an extremely low-risk procedure – the study had actually shown it was even safer than previously believed -- complications rise too. Someone who doesn’t want to be pregnant anymore likely isn’t interested in drawing out the process, either.

“When you talk about, where’s the evidence of lack of access,” Weitz continued, “it’s in the disparity in the number of low-income women geographically located in [remote areas]…who do not access their abortion until later in the second trimester.”

In other words, lifting the barriers would make it easier for women to get abortions earlier in pregnancy.

California is friendly terrain for reproductive rights, but it’s also enormous. The nurse practitioner in Eureka knew what Weitz was talking about firsthand. “What we see here in Humboldt County is what a lot of the rural areas in California see -- it’s hard to get and retain health practitioners,” she told msnbc. “There is a shortage especially in primary care, and up in Humboldt, we are it.”

One day, a patient had called about her appointment for a first-trimester abortion with a doctor at the Eureka clinic. “The people that were supposed to give her a ride had had their car impounded, so she had no transportation,” the nurse practitioner recalled. “She couldn’t get here that day and she was going to go over the line, time-wise.”

Until the nurse practitioner was added to the daily ranks, the Eureka clinic only had a doctor who would come one day a week to provide abortions up to 13 weeks and six days.

For the woman who had lost her transportation, having to wait a whole extra week was going to mean the difference between getting a ride to Eureka and getting a ride to Santa Rosa or Chico, each nearly four hours away.

"They made a huge effort to uplift the voices of young women, particularly young women of color."'

Seeing the nurse practitioner would also mean a familiar face. “The idea that abortion should occur in the settings where women get primary care was very important to us,” said Maggie Crosby of the ACLU of Northern California, who also testified that day. “That meant they could get abortions from clinicians they know and trust.”

And it would be a departure from the status quo in most places, where segregating abortion from other kinds of medical care has helped single out abortion providers for violence and abortion patients for stigma.

At the committee hearing that April day, one Assemblywoman, Holly Mitchell – now a state senator and chair of California’s Legislative Black Caucus -- had another answer for her colleague who wanted to see proof that women needed more access to abortion.

Mitchell said she was speaking as a woman who “represents a district filled with women who probably weren’t able to travel up here today because they’re working jobs, or they’re taking care of their families, or they’re looking for access to care as we speak. They may not have been able to travel to Sacramento on this one bill, this one day. I represent those women every day.” She added, “That’s why they elect people like me to bring their voice to this body. And so with that, I’ll be supporting the bill.”

…

The same summer that AB 154 cleared the California legislature, Texas was hurtling in the opposite direction. It passed a law requiring admitting privileges for physicians providing abortions at a local hospital and forbidding them from using an off-label regimen for medication abortion. The state will soon will require that abortions only be provided in ambulatory surgical centers.

It all sounds very medical – indeed, its supporters claimed the provisions promote women’s health -- but not if you ask the actual medical community. Both the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have argued in a court brief that “there is simply no medical basis” for the Texas law. That hasn’t stopped nearly half of U.S. states from passing similar laws.

The Supreme Court will likely eventually decide whether creating laws to shut down abortion clinics is unconstitutional. But as Crosby and other legal observers have argued, the Court's last abortion decision, upholding the "partial birth abortion ban" in Gonzalez v. Carhart, already opened the door to laws passed in contravention of scientific consensus.

That leaves California, as Crosby put it, as “one of the few states whose reproductive health laws are based on science.”

But even here, it was a long game. Being proactive about expanding access to abortion services, and not just playing defense against restrictions, was years in the making.

Weitz’s study formally began nearly a decade ago, and because it involved getting a waiver from the requirements that only doctors provide abortions (except for medication abortions) meant navigating massive red tape and politics. Once anti-abortion groups caught wind of the study, they did everything they could to block it, including trying to undermine its confidentiality and introduce legislation to halt the research.

Even beyond the particular politics of abortion were the internal fights within the medical community about scope of practice – who was allowed to do what, and under what terms. Abortion is unique in that providing it has such ancillary costs that doctors generally don't feel that proprietary about it. Still, there were turf battles with other players. In its first round in 2012, the bill failed in part because it hadn’t secured the support of powerful groups like the California Nurses Association. The bill’s supporters weren’t going to make that mistake again. By 2013, the California Medical Association and the California Academy of Family Physicians supported the bill, and other major groups, including the Nurses Association, stayed neutral.

That first year, it couldn't have helped that it was an election year. “Even in California, legislators don’t want to vote for abortion access, though they’re happy to vote against restrictions,” says Parker Dockray, who was the director of the California Coalition for Reproductive Freedom at the time.

But the bills' supporters had a major ally in the legislature, Assemblywoman Toni Atkins (then the whip, now the speaker) who once worked as an administrator at several abortion clinics. By 2013, they had a Democratic supermajority in both chambers. In October 2013, AB154 was signed by Governor Jerry Brown.

…

Much of the conversation around AB154 was about rural women, but Samara Azam-Yu thinks it will make a difference in cities, too.

Azam-Yu is the executive director of ACCESS, which runs a bilingual reproductive care hotline for California women. They recently took a call from a woman in West Oakland who had barely been out of the neighborhood and who never set foot on BART, the area’s public train system. She made $8 a week in commissions at a salon.

“People underestimate the amount of isolation in urban areas,” said Azam-Yu.

Ena Suseth Valladares, director of research for California Latinas for Reproductive Justice, agreed.

“A lot of Latinas who live in rural areas, as well as those who live in urban areas, will benefit because their health care provider now is most likely a nurse practitioner or a physician’s assistant,” she said.

Both groups co-sponsored the bill, highlighting another reason for its success: Diverse, grassroots support. “They made a huge effort to uplift the voices of young women, particularly young women of color,” said Azam-Yu.

Another co-sponsor was Black Women for Wellness, a reproductive justice organization with nearly two decades of work in South Los Angeles. “We wanted to make sure that legislators knew that black women care about this issue and that we work on abortion rights,” said Nourbese Flint, the group’s program manager.

Their participation helped broaden support in the face of longstanding concerns that the abortion rights movement is overwhelmingly white, older, and middle-class.

(The same coalition also came together to support the repeal of the maximum family grant, which restricts welfare benefits for additional children born to a family already receiving benefits. That bill, introduced by Mitchell, has yet to pass.)

It also was a ground-level riposte to the opponents’ claim that women of color would receive substandard care under the law. Anyway, in the face of Weitz’s thousands-strong study, which showed complication rates of less than 2 percent, it was hard to take those claims seriously.

In January, after opponents failed to gather enough support for a ballot referendum to repeal it, AB154 took effect, with little fanfare outside the staff kitchen at the Six Rivers Planned Parenthood. That was the idea.