BALTIMORE — On the November night in 2008 when the nation elected its first black president, wild celebrations broke out in west Baltimore. But when Perry Hopkins jumped up from the steps of the Chinese takeout where he was sitting and tried to join the party, he was quickly put in his place.

“Somebody looked at me and said: You got a record, you can’t vote. You ain’t got nothing to do with this, you can’t claim this,” Hopkins recalled. “And it hurt.”

A wiry, intense 54-year-old, Hopkins has been barred from voting thanks to an extensive criminal history that he attributes to a past addiction problem. “I’ve done five years three times, and four years once, so I’ve got roughly 20 years on the installment plan,” he said. “I’m not proud of it, but it’s the truth.”

Of being disenfranchised, Hopkins said: “I felt like my hands were tied behind my back and I was being beaten."

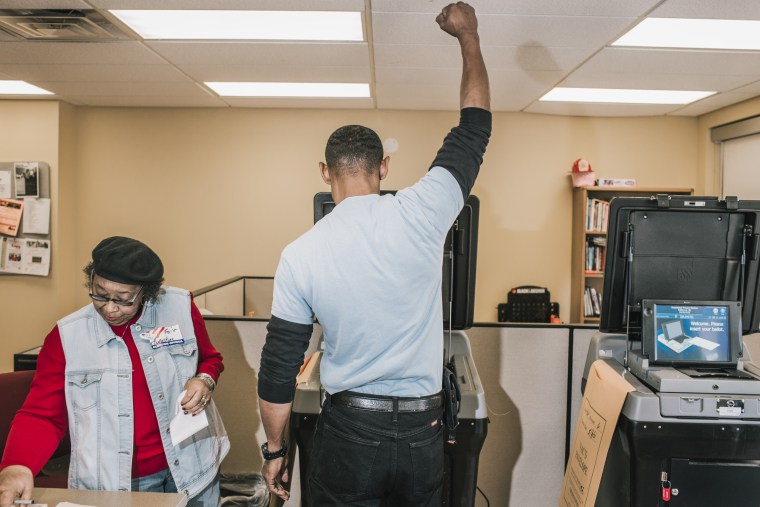

Now that feeling is gone. On Thursday, Hopkins cast his first votes ever in Maryland’s presidential and mayoral primaries. (He won’t say for whom he voted.) And as an organizer for Communities United, a local community group, he rounded up scores of his neighbors — many of them also former felons — and drove them in a van to the polls, too. “Hey, come vote!” Hopkins was shouting to anyone who would listen Thursday as he stood at a busy intersection, loading up another van with people.

In February, prodded by a grassroots campaign by Communities United and other voting rights and civil rights groups, Maryland restored voting rights to people with felony convictions as soon as they’re released from prison — re-enfranchising an estimated 40,000 predominantly African-American Marylanders. Previously, they’d had to wait until they had completed probation or parole. Democratic lawmakers overrode a veto by Maryland’s Republican governor to push the measure into law. Communities United says it's registered about 1300 new voters since the law passed.

RELATED: New York probing primary election problems

The move was perhaps the biggest victory yet for a nationwide movement to scrap or weaken felon disenfranchisement laws, which shut nearly 6 million Americans, disproportionately non-white, out of the political process.

On Friday, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe announced an executive order that re-enfranchises more than 200,000 felons, a move that could boost Democrats in the crucial swing state this November. Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin last week signed a law that softens that state's felon voting ban. And a ruling by the Iowa Supreme Court, expected imminently, could dramatically reduce the number of crimes that lead to disenfranchisement there.

In Maryland, opponents of the change argued that it makes sense to require former felons to complete their full sentence — meaning probation or parole — before getting their rights back. But several of the newly re-enfranchised who Hopkins ferried to the polls Thursday said emphatically that the right to vote was itself a powerful spur toward reintegrating back into society.

“Not being able to vote was hindering me from actually being considered as a full citizen, and it was hindering my whole rehabilitation process,” said Reginald Smith, moments after voting for the first time in decades. “Because I was still being punished for something that I already served time for.”

“Being able to vote, it just makes me feel that much more positive about myself,” said Robert Mackin, 54, shortly before he cast the first ballot of his life. (Who did Mackin plan to vote for? “I sure know it ain’t gonna be no Trump.”)

RELATED: Why does New York make it so hard to vote?

“I believe my word is just as good as the next man in line,” added Mackin, who said he’s been in and out of prison since he was 18. “I have opinions. I’m on this earth, I’m of age. I work and pay my taxes, too. So why can’t I have a say on what’s going on?”

“A long time coming,” Trina Ashley exulted, moments after casting her first ballot — for Hillary Clinton and Sheila Dixon, a candidate in the mayoral race.

Ashley has been back home since completing an eight-year prison sentence in 2000 for what she described as “a misdemeanor that they labeled a felony.” Being disenfranchised felt “like I still had the chains on me, like I was still locked down,” Ashley said. “Now, not all the chains are gone. But at least one of them is gone.”

Michael Watt, 39, was another former felon voting for the first time. As he bought a hot-dog for his 4-year-old son Max, Watt said that, like Hopkins, he felt left out when his friends and family were celebrating President Obama’s election.

“We went out to Friday’s, and it was like a fun night,” Watt remembered. “But I felt ostracized because I was the only one that wasn’t able to cast a ballot.”

Now that he can, Watt said, it feels “like a breath of fresh air.”

The change offers more than personal milestones. Baltimore's black community has been galvanized by the death in police custody last year of Freddie Gray, which led to days of sometimes violent protests and a political mobilization aimed at holding city and police leaders accountable.

“Politicians and elected officials, they never had to pay attention to this group of people. They could do what they wanted to us.” Hopkins said. “But you got to recognize us now.

“I’m gonna vote every time I can for the rest of my life,” Hopkins added. “It’s important.”