It has been more than two decades since the Veterans Administration was elevated to a cabinet department. But its dreary public image endures and not without reason: veterans wait a staggering average of nine months for their disability claims to be processed and the delay gets longer all the time.

In a stark departure from how he has operated until now, Secretary Eric Shinseki, who oversees the administration, is seeking to change the public perception. I interviewed him on March 27th during his visit to a veterans’ jobs fair in New York City.

Shinseki, a retired Army general, was twice wounded in Vietnam. As Army chief of staff, he incurred the opprobrium of the Pentagon’s civilian leadership in 2003 by delivering news it didn’t want to hear: A large number of American troops would be required to secure Iraq once Saddam Hussein was deposed. So, although he is a shy, modest man, he’s not necessarily a shrinking violet. Nevertheless, amid the inability of the VA to cope with the logjam of claims, Shinseki has not been much of a visible presence outside his department. Until now.

Shinseki’s main message for the public, and his critics, is that veterans who need medical care are enrolled for treatment right away. While the quality of care varies from hospital to hospital, and veterans in sparsely populated areas need to travel some distance to a facility, there seem to be no bureaucratic impediments to timely medical care.

However, the large and persistent problem is the enormous and growing backlog of claims for disability benefits.

Ironically, one reason may be Shinseki’s own decision to do the right thing. Troops with post-traumatic stress, and Vietnam-era vets exposed to Agent Orange, were not entitled to benefits. In 2009, Shinseki changed that, allowing these two large groups to become eligible to apply for payments. But, as is often the case when bureaucracies have to respond to new requirements, the VA couldn’t---and still can’t---process these applications without frustratingly long delays.

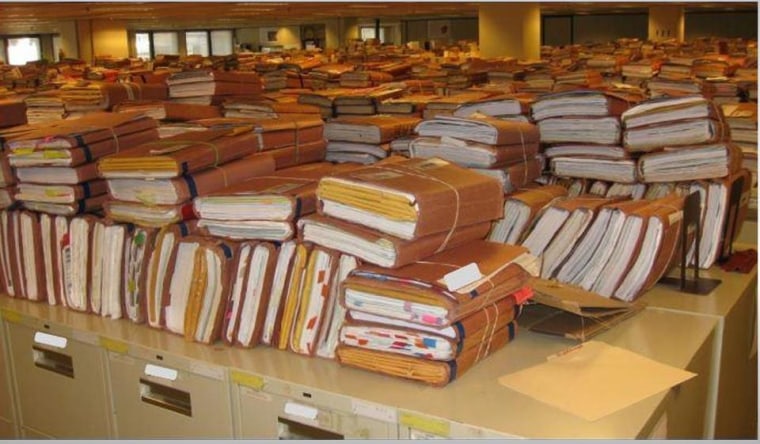

How could this be? The VA claims system, which deals with thousands and thousands of claims, is not digitized and instead relies on hard-copy paper. It will take another two and a half years to bring the VA’s snail-paced system into the 21st century to fulfill the obligations Shinseki has placed upon it.

In our interview, Shinseki acknowledged the burden his decisions were having on an antiquated system but said more veterans needed access right away.

“I think they deserve the benefits, and I didn’t think it was right to wait.”

At a time when the entire government is slashing expenditures, Shinseki has managed to get a huge increase in his budget, an enormous success in the cutthroat arena of Washington. And nobody could be faulted for concluding that he is doing the right thing.

But for an increasingly dissatisfied constituency, good intentions don’t count for much. No matter how honorable the effort, the claims backlog has so far stubbornly refused to yield, and as long as veterans expect benefits and don’t get them, the VA and its boss will continue to take the heat.