Chapter 1

DELTA BRAVO APRIL 7, 2010, MILTON, VERMONT I dialed the strange number with a sequence of digits too long to remember. The tone beeped in a distinctly foreign way. My call went through to Afghanistan. “Hello, Duncan? This is Michael Hastings from Rolling Stone.” I was in a house on Lake Champlain, smoking a cigarette on a screened-in porch with a view of the Adirondacks. I put the smoke out in an empty citronella candle, went inside, and grabbed a notebook from the kitchen counter. Duncan Boothby was the top civilian press advisor to General Stanley McChrystal, the commanding general of all U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan. Duncan and I had been e-mailing back and forth for a month to arrange a magazine profile I was planning to write about the general. I’d missed his call yesterday. He’d left a message. This was the first time I’d spoken to him. Duncan had a slight British accent, ambiguous, watered down. He told me I should come to Paris, France.

“We’re going to discreetly remind the Europeans that we bailed their ass out once,” he said. “It’s time for them to hold fast.” Duncan explained the plan. The visual: Normandy. D-day. The Allied forces’ greatest triumph. Bodies washed ashore then, rows of white crosses now. The scene: McChrystal standing on the banks of the English Channel, remembering the fallen, a cold spring wind blowing up from Omaha Beach. He’s a “war geek,” Duncan said; he spends his vacations at battle¬fields. A few months ago, on a trip back to DC, on his day off he went to Gettysburg. The narrative: The trip is part of a yearlong effort for McChrystal to visit all forty-four of the allies involved in the war in Afghanistan. This time, it’s Paris, Berlin, Warsaw, and Prague. It’s to shore up support among our friends in NATO—to put to rest what Duncan called “those funny European feelings about the Americanization of the war.” From my perspective, he told me, there would be something new to write about. No one had ever profiled McChrystal in Europe. Duncan was a talker. He hinted: I’m in the know. I’m in the loop. I’m in the room. “What do you make of Karzai’s outburst the other day?” I asked. Ha-mid Karzai, the U.S. ally and Afghan president, had threatened to join the Taliban, the U.S. enemy. He’d done so just days after President Barack Obama had met with him. “That make life difficult for you?” Duncan blamed the White House. “The White House is in attack mode,” he said. “It took President Obama a long time to get to Kabul. They threw the trip together at the last minute. We had six hours to get it ready. Then they came out of the meeting saying how much they slammed Karzai. That insulted him.” I took notes. This was good stuff. Duncan spun for McChrystal—the general had invested months of his time to develop a friendship with the Afghan president. “Karzai is a leader with strengths and weaknesses,” he said. “My guy has inherited that relationship. Holbrooke and the U.S. ambassador are leaking things, saying they can’t work with him. That undercuts our abil¬ity to work with him. For the McCains and the Kerrys to turn up, have a meeting with Karzai, criticize him at the airport press conference, then get back for the Sunday talk shows. Frankly, it’s not very helpful.” I was surprised by his candidness. He was giving me his critique over the phone, on an unsecured line. “This is close-hold,” Duncan said, using a military phrase for ex¬tremely sensitive information. “We don’t like to discuss our movements. But I would suggest getting to Paris next week. Wednesday or Thursday. We’ll do the trip to Normandy on Saturday.” “Okay, great, yeah,” I said. “So I’ll plan to meet up with you guys next week. For travel, the main thing is—” “You’ll probably want to go to an event with us on Friday at the Arc de Triomphe, maybe sit down for an interview with The Boss, then take a train out to Normandy, and meet us there.” “Cool. As much as I can get inside the bubble, I mean, travel inside the bubble.” “I’ll let you know on the bubble.” He hung up. I e-mailed my editor at Rolling Stone: “Can I go to Paris?” Chapter 2

IT’S NOT SWITZERLAND SEPTEMBER TO NOVEMBER 2008, KABUL A handful of staffers are watching television on the 32-inch flat screen outside the office of General David McKiernan at the International Secu¬rity Assistance Force (ISAF) headquarters in Kabul. The buildings that house ISAF (pronounced eye-saf ) used to be home to a sporting club for the wealthiest in Afghanistan, but for the last eight years it’s been the headquarters for a succession of American generals who have run the war in this country. It doesn’t have the harsh look usually associated with a U.S. military base: There are trees, manicured lawns, and a beer garden with a wooden gazebo. Guard towers overlooking the garden are perched on cobblestone walls, just refurbished by the Turks, with shiny new pan¬eling, like the interior of a Hilton Garden Inn. It’s 7:00 a.m. on September 4 in Afghanistan, 9:30 p.m. on Septem¬ber 3 in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Sarah Palin is on the screen. She’s giving her acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention. She’s get¬ting cheers from the crowd, the crowd is going nuts, but it’s too early in the morning in Kabul for anybody to be excited. The door to McKiernan’s office is open—it looks like a headmaster’s office at a boarding school, all dark oak and thick carpet—and the general passes in and out, checking early-morning e-mail. He overhears a few lines of Palin’s speech as she gushes about her husband, Todd. “Sounds like someone’s running for prom queen,” McKiernan says with a smile. McKiernan has more than a passing interest in the 2008 presidential election. The next commander in chief is going to be his boss. He’s been on the job since June, planning to stay for a two-year tour. It’s what he’d promised the Afghan generals, the diplomats, and his NATO allies. It’s the fifty-seven-year-old general’s second chance to run a war. He got screwed in Iraq. He pissed off Don Rumsfeld, and Don Rumsfeld doesn’t forget. McKiernan was in charge of invading that country, and his plan called for more troops to prevent an insurgency from springing up. Rumsfeld didn’t want to hear it; Rumsfeld wanted to go in as small as possible. (And, by the way, a year earlier, McKiernan had testified to de¬fend the Crusader artillery weapons system, a program Rumsfeld wanted killed.) After seeing McKiernan in Iraq, Rumsfeld judges the general to be “a grouch, resisting the secretary of defense,” as one retired admiral who advised the Pentagon puts it. So after Baghdad falls, McKiernan is supposed to take over. Doesn’t happen. He ends up in limbo, or what passes for limbo when your coun¬try is at war in two countries—commanding the U.S. Army in Europe. His promotion to fourth star gets held up. He doesn’t get it for two more years, and even then over Rumsfeld’s objections. During that time, the military world is changing. Iraq is a mess. Americans blame Bush, they blame Rumsfeld, they blame neoconserva¬tives, oil men, Israel, the media, Dick Cheney, Halliburton, Blackwater, Saddam. The U.S. military, by and large, escapes the blame—they were just following orders. The public gives them a pass. Not so within the ranks: There’s score-settling and finger-pointing going on. The finger points to an entire generation of military command¬ers. The poster boy is General George Casey—he oversaw Iraq’s complete spiral to @!$%# and didn’t stop it, didn’t adapt, or so the story goes. He’s got gray hair. He’s old-school. To top it off, Casey gets promoted to Army Chief of Staff—he gets rewarded for the mess. McKiernan is old-school, too. He’s not one of these new-school gen¬erals, like a Dave Petraeus or a Stan McChrystal. Petraeus already has a historic reputation, and McChrystal is an up-and-coming star, currently working on the Joint Staff at the Pentagon. McKiernan is part of the old generation, or so they claim. He gets dubbed the Quiet Commander; headlines call him “low-key” during his time in Iraq. Even in the midst of an invasion, “he is rarely known to swear.” “In any type of a chaotic situation,” another general says of him, “he’ll be in the middle of it, di¬recting things without emotion.” He’s a golfer, shoots in the seventies. He was on the debate team in high school. His best friend growing up says he “tended to be shy.” He hates PowerPoint and prefers a “walkabout style” of leadership to long-winded briefings, according to his colleagues. He doesn’t have a deep fan base in the media, either. He doesn’t like to get his picture taken, doesn’t suck up enough when visitors from Con¬gress come over to check out the front lines. McKiernan wouldn’t think to send an autographed picture of himself to a journalist, as David Pe¬traeus once did. That’s not McKiernan’s style—he doesn’t even have a good nickname. At over six feet, with silver hair and a handsome square-jawed face, he could be typecast as the father in a teen movie who scares the hell out of any boy stupid enough to take his daughter to the prom. He still gets his shot at Afghanistan, though. He’s next in line. The old school rules still hold sway on the promotion board. It’s been a bit of an awkward transition, partly because President Bush wants to pass off Afghanistan to the next president. McKiernan says a few things that aren’t quite diplomatic: He notes that some of those European allies seem to treat war “like summer camp.” Even more awkwardly, in October, Dave Petraeus, once his underling, now becomes his superior. Dave gets the job as CENTCOM commander, which means he has over¬sight of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Not the worst situation, he thinks, just a bit uncomfortable. A month after Palin’s acceptance speech, the presidential election is on television again at ISAF HQ. This time, the staff gathers to watch the vice presidential debate. It’s Senator Joe Biden from Delaware, squaring off against the governor of Alaska, Palin. Afghanistan is a hot topic in the debate, and they’re listening to see where the candidates stand, what they can expect. McKiernan has had a troop request on the table at the White House for months, asking for some thirty thousand more soldiers. The White House has resisted—they want NATO to pony up the reserves, and McKiernan is hoping the next administration will give him the sol¬diers he’s asked for. Palin and Biden agree: more troops and resources to Afghanistan. What they don’t agree on is McKiernan’s name. Palin keeps calling him “McClellan”; two times she says it. (The staff breaks out laughing, in¬credulous; a McKiernan advisor pings an e-mail to the general, joking about how Palin got his name wrong.) Biden resists the urge to correct her. Instead, he points out that McCain, her running mate, has said, “The reason we don’t read about Afghanistan anymore in the paper [is that] it’s succeeded.” Afghanistan: an American success story. The media dub it the For¬gotten War. The nightmare in Iraq overshadows the conflict. The United States regularly declares success in Afghanistan, despite mounting evi¬dence to the contrary. A year doesn’t pass without public declarations of progress. In 2001, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld says, “It’s not a quagmire.” In 2003, the commanding general in Afghanistan says that U.S. forces should be down to 4,500 soldiers by the end of the following summer. After that summer, General John P. Abizaid says the Taliban “is increasingly ineffective.” In 2005, the Taliban is “collapsing,” says Gen¬eral Dave Barno. In 2007, we are “prevailing against the effects of pro¬longed war,” declares Major General Robert Durbin. In 2008, General Dan McNeill claims that “my successor will find an insurgency here, but it is not spreading.” That same year, Defense Secretary Robert Gates as¬sures us we have a “very successful counterinsurgency,” and we won’t need a “larger western footprint” in the country. The United States is spending every three months in Iraq what they’d spend in an entire year in Af¬ghanistan; there are over thirty thousand troops in Afghanistan, about one quarter of the number deployed in Iraq. McKiernan recognizes the trend lines aren’t great. Since 2006, vio¬lence has spiked dramatically, from two thousand annual attacks to over four thousand in 2008. American and NATO soldiers are getting killed at a rate of nearly one per day. Civilian casualties have tripled over the past three years, killing a total of approximately 4,570 people. The more U.S. and NATO troops added, the worse the violence gets. The Taliban has regained control over key provinces, including those surrounding the country’s capital. On October 13, a New York Times reporter writes a story suggesting we’re losing. McKiernan dismisses it; the guy “was only in town for a week.” But yes, things aren’t good. McKiernan gets a classi¬fied report from America’s seventeen intelligence agencies saying the prognosis is “grim.” McKiernan wants those troops to hold the line— who’s going to be the next commander in chief? A few weeks after the vice presidential debate, Lieutenant General Doug Lute, head of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan policies at the White House, visits McKiernan in Kabul. A White House staffer nicknames Lute “General White Flag”—he likes to surrender. It’s not a nice nick¬name. He didn’t want to surge in Iraq, and he’s skeptical on Afghanistan. He tells McKiernan that Obama has it locked up; it’s a foregone conclu¬sion, Lute says. Obama is going to be the next president. Which is fine with McKiernan. During the campaign, Obama an¬nounces after he returns from a visit to Kabul that he’d give McKiernan “the troops he needed.” McKiernan is impressed when he meets Obama that summer; he speaks to the senator in a phone call again before the election. He wants to build the relationship, quietly. And—let’s face it— McCain is an @!$%#, thinks he’s a military genius. Palin can’t even get his name right. McKiernan, although he would never say so publicly, is pulling for Obama, a senior military official close to him tells me. McKiernan is suspicious of McCain, too, because McCain views Pe¬traeus as some kind of godlike figure. Anyone so close to Petraeus can’t be good for McKiernan. He’s waiting for the full attention to get back to Afghanistan. On November 4, 2008, Obama wins the election. McKiernan is working up a new strategy to get to the president—three strategic reviews are going on, one at ISAF, one at CENTCOM, and one in the Bush White House. Lots of wacky ideas are being thrown about: The CIA has a plan to just withdraw everyone and go total psyops—like broadcasting horrible atrocities of ISAF soldiers to scare the @!$%# out of the Taliban. McKiernan’s plan calls for a comprehensive counterinsurgency strategy. It’s heavy on training Afghan security forces—he puts the date of how long it’s going to take at 2014, at the earliest. He sees the country’s limita¬tions: “There’s no way this place is going to be the next Switzerland,” he tells me during an interview that fall in Kabul.

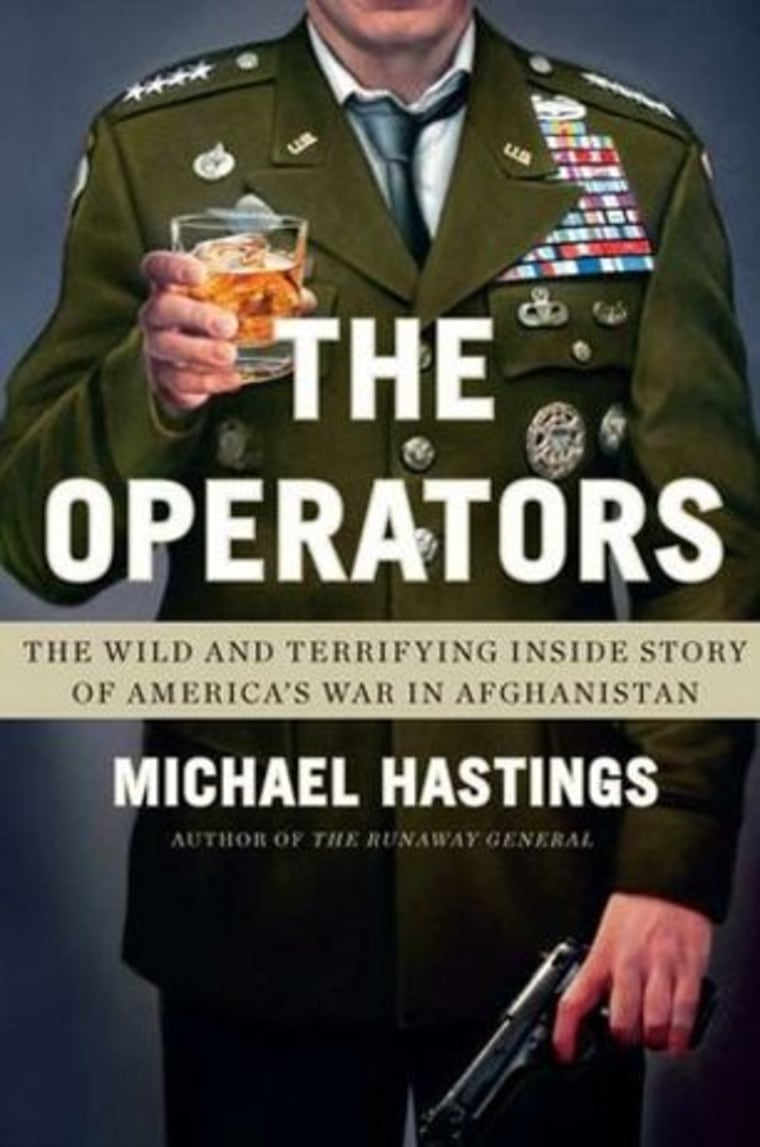

To order a copy of the book, click here.