A Puppy and a Patch of Grass

By Jon Meacham

About two years ago, my wife and I made a slightly impulsive decision to move from New York City, where we had lived happily for close to two decades, to Nashville. Though announcing this to our New York friends didn’t provoke the same reaction as, say, reporting that we were divorcing or that one of us had been stricken by disease, I do suspect we’d have gotten similar looks of mystification, puzzlement, and pity had our news been of a more traditionally calamitous nature.

It’s a familiar leaving–New York ritual. One friend, a woman of Southern roots long resident in the North, wondered how we could give up a life where any problem could be solved by three magic words: “Call the super.” The question people asked with the greatest frequency and bewilderment was simple yet profound, and certainly existential: Why?

“Grass and dogs,” we’d reply.

Yes, our answer was glib, but as Henry Kissinger used to say, it also had the virtue of being true. I grew up in Chattanooga, my wife in Mississippi, in both the Delta and

Jackson. We have three children, all of whom, at that time, were under the age of ten. When our first child was born, we bought a house in Sewanee, Tennessee, the tiny Episcopal college town William Alexander Percy wisely christened Arcadia. Our wishful thinking was that ten months on the Upper East Side and summers on the Cumberland Plateau would be the perfect combination of differing cultures and climate for children who were Southern by blood if not birth.

As the years passed, however, it grew ever more difficult to pack up and re-migrate to Madison Avenue at the end of August. The brave new world of acreage, the freedom of being able to go out the front door and into something as radical as a yard, led us both to surreptitious online real-estate searches of suburban New York. It occurred to us, finally, that instead of trying to replicate the South we could just return to the real thing. Nashville seemed (and has proved) the perfect place.

The “grass” part of the equation was handled with some dis- patch. A Sewanee classmate of mine from Demopolis, Alabama, had a brilliant friend in real estate in Nashville (auspiciously, the only other woman I’ve ever met named Keith besides my wife). We bought the first house she showed us, a lovely if faded Georgian Revival with a glorious yard and a creek at the foot of a sloping hill. So we’d checked the first box.

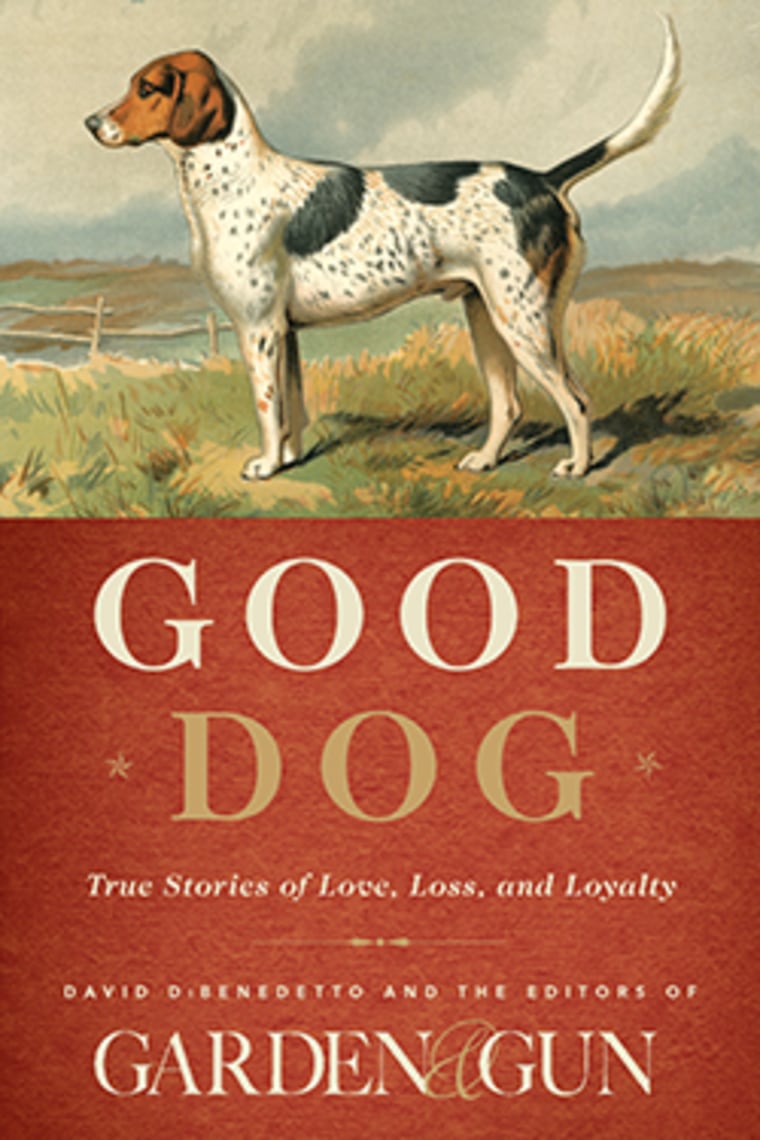

Now we needed the dog. As I think back on it, I believe there was more internal debate within the family over what kind of puppy we might get than there had been over the whole move itself. I had grown up with a liver-and-white English springer spaniel named Daphne, a brilliant hunter who merrily terrorized the quail on my grandfather’s farm near Blythe Ferry on the Tennessee River. To me the choice seemed obvious, even stipulated.

I had momentarily forgotten, however, that my son and I live in a family of women. My wife wanted a Lab of some kind; my older daughter, Mary, wanted a beagle, having been struck years earlier by a coup de foudre on meeting the Platonic ideal of the breed in Henry, her godmother Julia Reed’s exceptional dog; and the baby, then nearly four, was in solidarity with the sisterhood. Whatever the boys want, we want something else.

In domestic matters my son and I have a perennial political problem. There are three of them and only two of us. And they’re louder. I was working on a biography of Thomas Jefferson when said baby girl was born. Our son, Sam, then seven, when told that he was going to have another sister, thus giving the female caucus a majority, replied presciently, “But Daddy, that means we’re out- numbered.” This was the same reaction the Federalists had when Jefferson bought Louisiana, provoking a secessionist movement led by New Englanders worried, rightly, about the expanding power of the South and the West.

In a moment of historical identification, I decided that Jeffer- son’s strategy in the Louisiana crisis—to dispense with what he called “metaphysical subtleties” of constitutional law and move ahead unilaterally—had much to recommend it in our own un- folding canine crisis. Jefferson had created his own facts on the ground by pressing ahead with the purchase. So would I.

I called a friend in Nashville, a physician who had already made me feel very inadequate by asking me, before the deal on the house was closed, whether I had lined up a dentist yet, and asked him to hook me up with the local springer spaniel mafia. I figured there had to be one; what I had not figured on was Jim Sawyers, a self-described “dogman” based in Goodlettsville, just outside Nashville. Jim is kind of a dog NSA—he knows everything—and within hours, it seemed, he had found a liver-and-white English springer puppy in southern Ohio.

Within moments—and of this I am certain—of Ellie’s arrival, the acquisition of a springer had become everyone’s idea. (The same thing happened with Louisiana, by the way.) Beautifully marked, boundlessly energetic, and, it would turn out, sweetly theatrical, Ellie transformed the household. As she grew out of the cute waddling puppy stage into a lean early adolescence, she turned the yard into her magical kingdom. With balletic leaps out the door and over the steps, Ellie became a Belle Meade huntress, giving tireless chase to what our younger daughter, Maggie, calls “burrrds.”

Ellie’s daily hunting reminds us of Samuel Johnson’s remark about second marriages—they’re the triumph of hope over experience. We don’t think she has actually ever caught anything, save for one already dead rat she pitched up with one afternoon, but Lord, does she love the hunt. From my desk I can watch her spend a good hour or more in wearying pursuit of game in an open rectangle of boxwoods. I think the birds are taunting her, but I like to think they’re doing so somewhat affectionately. When the family of possums that live in the underbrush between our property and our neighbors’ amble by in the twilight, Ellie puts on a good show of scaring them. She doesn’t scare them at all, of course, but she likes to think she does.

She has a Shakespearean streak, a sense that all the world’s a stage. Prideful, she loves being watched as she bounds from one end of the yard to another. Galloping and leaping and preening and pointing and panting, she is incredibly fast, pausing only to try to climb tree trunks or to lift a front paw in what we’re certain she thinks is a flattering pose. (And she’s right about that.)

To think of her as a creature of the wild, however, would stretch things rather far. While Ellie adores digging for moles, jumping the creek, and pointing Southwest jets that are climbing out of Nashville airspace, she has also yet to find a bed in the house on which she is uncomfortable and finds it totally natural to join guests on the couch for drinks. She’s puzzled when she’s asked to leave—or, more accurately, when she’s dragged off. Keenly able to manipulate her expressions, she manages to convey a more-in- sorrow-than-in-anger look of amazement that we would be so out- rageous as to want some time without her licking a visitor.

She loves her house and her outdoor domain, and we like to think that she loves us. I won’t pretend to have any insights about the inner lives of dogs. But I do know this. When the door swings open every morning and a liberated Ellie leaps into the yard, seek- ing prey—whether “burrrds” or a jetliner—she does so with joy, springing out into the world, delighted to be free again. As are we.