I was there when the people of South Africa first got to vote. Along with the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is one of my all-time great experiences as a journalist.

“Who said we don’t care? Who said we’re not politically sophisticated?”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was looking at the biblical length of South Africans waiting in line to vote that Wednesday morning. He was saluting what his ally, Nelson Mandela, had done to lead his country into democracy.

This sight, of millions of people – black, white, mixed race and Asian – all voting peaceably is something few South Africans thought would ever happen. The historic picture they had expected to see was a final, bloody battle between the diehard defenders of apartheid and the black masses.

Instead, it had come to this: a peaceful election with all the people of South Africa standing in the same lines waiting to vote.

It was not only the black majority that was hoping for the historic moment of change. “This is the day I’ve been waiting for all my life,” a young white woman told me as she stood in a long line of voters that morning in April 1994.

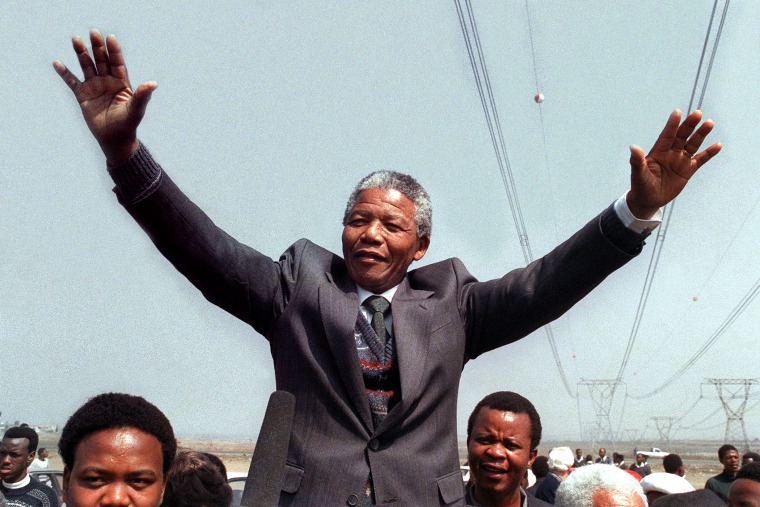

It was all happening this way – the democratic way – because of one man, Nelson Mandela.

“My vision of South Africa has been one which has a Bill of Rights which guarantees the rights of every South African regardless of race,” he told me in an election-time interview. He spoke of his 28 years in prison and how it had strengthened his commitment to a non-racial, multi-ethnic democracy.

“In prison, the authorities tried to cut me off completely from the outside world. But no measures they took could prevent us from knowing what was going on outside. We have always been very clear that the ideas for which we were suffering were going to triumph because we could see a stiffening of the resistance against racial repression from our people and the strong support we were receiving from the international community.”

I had begun election morning with a 6 AM mass said by Desmond Tutu, the Anglican archbishop of Cape Town. “Thank you for bringing us to this day,” he prayed that Wednesday morning, “when all the people shall be able to vote for their elected government.”

He prayed, too, for the right-wing whites who were trying to disrupt the first-ever all-races election. “We pray that you turn the hearts of those who want to use evil methods.” To sanctify the point, Tutu performed the consecration in both his native Xhosa and in Afrikaans, the language of his oppressors.

It was now 6:30 AM, Cape Town time – Time to bolt! The race was on from the archbishop’s leafy neighborhood to one to Gugulethu, one of the poorest, and most dangerous townships in the country. At 62, the archbishop wanted to cast the first vote of his life.

“Yippee!” he roared as he arrived at the plain cinder block building. “It’s how I feel. I can’t say it any other way. Fantastic! Fabulous! The day has come. Here we are voting.”

When we returned to his residence, after touring many of Cape Town’s voting places and seeing the huge crowds, Tutu calmly described the humiliation of apartheid.

“It is difficult to tell you how it felt.”

He told of what it was like to be a black man under white rule. He told having to explain to his young daughter that she couldn’t play on a swing that other white children were using.

“And you had to say, ‘No, darling, you can’t.’ You couldn’t look into the eyes of your child to tell her, ‘No, darling, those swings are for the white children.’”

In April 1994, the swings ceased to be for just the white children. South Africa became a democracy and the great Nelson Mandela became its first truly elected President.