Linda Sandefur has a Master’s degree and two decades of administrative experience. She's filled out 93 applications since losing her job in June but is still struggling to find work. Living in Michigan, which cut its unemployment aid, Sandefur got six fewer weeks of benefits than most jobless Americans—and now her extended federal benefits could end, too. ”My sister only works part-time, my mom’s on Social Security, and we’re barely making a go of it,” says Sandefur, 49, who lives with her relatives in Brant, Michigan.

Since the beginning of the recession, seven states have cut their unemployment benefits to less than 26 weeks—the prevailing standard since the 1950s. So far, emergency federal benefits have cushioned the blow of most of these cuts, kicking in after state benefits expire. But at the end of December, those federal benefits are scheduled to disappear as well, cutting off unemployment checks to 1.3 million jobless Americans and delivering a double whammy to states that have already reduced their benefit weeks to historic lows.

In addition to the 1.3 million who would lose their benefits immediately, the expiration of federal benefits would affect 3.5 million more jobless Americans by the end of 2014. That's how many unemployed workers are still expected to be job-hunting after their state benefits expire, according to the Obama administration, which is pressing to continue the emergency federal aid as part of a year-end budget deal.

The end to federal benefits would deal a particularly sharp blow to jobless Americans in states that have already cut back their own unemployment programs to ease the debt they've taken on to pay for them. Michigan has already cut state benefits for unemployed workers like Sandefur down from 26 to 20 weeks. Georgia, Missouri, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Illinois, and Arkansas have also cut anywhere between 1 and 14 weeks of state benefits. Some states have also made it harder to qualify for aid and have shrunk their checks as well.

States haven’t been this stingy toward the jobless since the 1950s.

Up until now, jobless workers everywhere but North Carolina have been able to rely on the federal benefits to make up for their states' cutbacks. "The federal extension in place kind of camouflaged what they have done," says George Wentworth, an attorney at the National Employment Law Project. But now those federal benefits are on the chopping block as well, scheduled to expire December 29 unless Congress decides otherwise.

Congressional Democrats and the Obama administration are trying to stop the unemployment cliff. "That abrupt transition—one day you have it, one day you don't—is going to a huge burden. There are people who are out looking for work who are receiving it, and they're depending upon it," says Sen. Jack Reed of Rhode Island. During 2012's fiscal cliff talks, Congressional leaders agreed to a year-long extension of the benefits, and Democrats are hoping for a similar deal this time around. "Senator Murray is very interested in finding a path to an extension before the end of the year," said Eli Zupnick, a spokesman for Patty Murray, a lead Democratic budget negotiator.

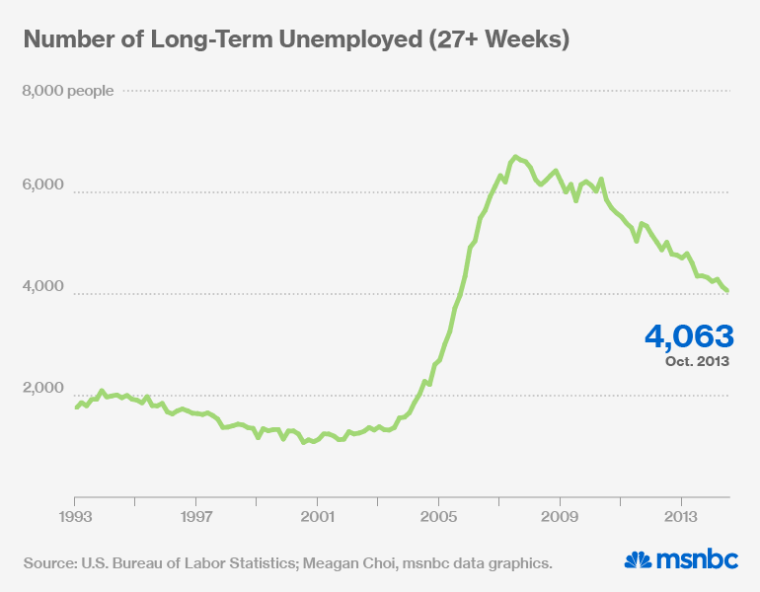

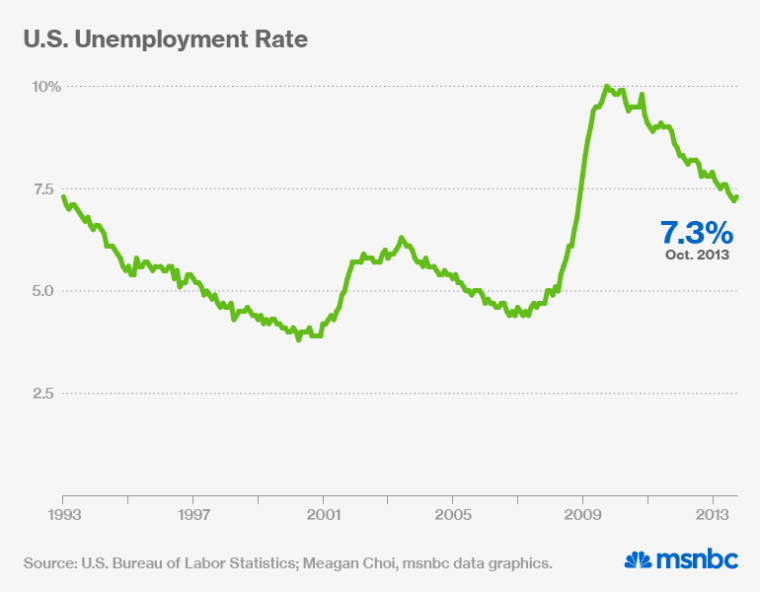

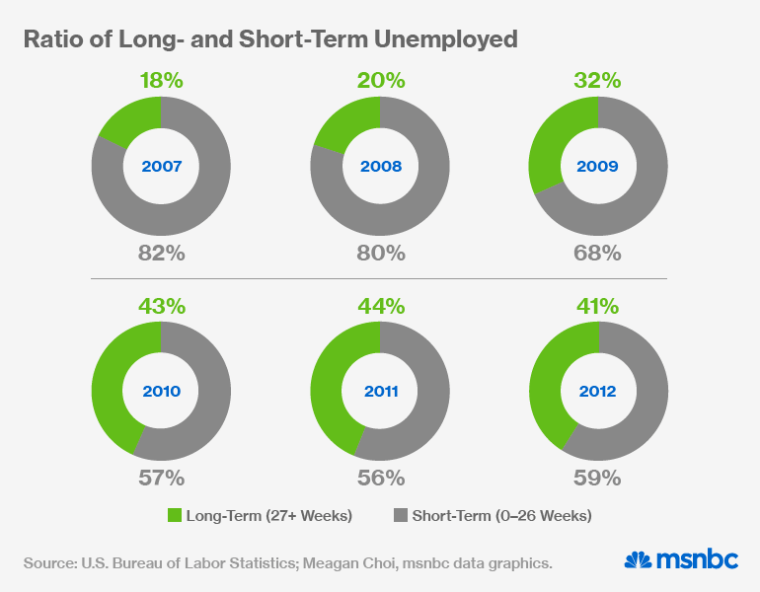

The emergency unemployment aid has been at the heart of Congress's response to the recession, and Democrats argue the help is still necessary given the state of the labor market. Though unemployment has fallen from the post-crisis high of 10.2 percent to 7.3 percent, there are 4.1 million Americans who have been out of work for more than 26 weeks. The long-term unemployed still make up more than one-third of all unemployed workers. "That's higher than at any point prior to the Great Recession, going back to the mid-1970s," says Henry Farber, an economist at Princeton University.

Democrats also point out that ending federal benefits would dampen economic growth, as those who receive them to tend spend the money quickly. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody's Analytics, estimates that letting the benefits expire would reduced GDP growth in 2014 by 0.16 percentage points, or nearly $25 billion.

But Republicans aren't keen on the idea of continuing the aid. "This program—which has already added too much to the deficit, and helped keep unemployment too high for too long—should be allowed to finally come to an end," said Rep. David Camp, chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, arguing that the program has actually raised the unemployment rate by deterring workers from taking jobs.

It's also highly unclear how the program will be incorporated into a budget agreement, which Democrats and Republicans are still far from reaching. In 2012, the year-long extension cost $30 billion, and politically feasible offsets remain scarce.

Congress has already scaled back federal unemployment benefits since the height of the recession, when they hit an unprecendented length of 73 weeks; combined with the standard 26 weeks of state benefits, the aid to the jobless lasted as long as 99 weeks. Federal benefits now last anywhere between 14 and 47 weeks, depending the state's unemployment rate and length of their own benefit period. (Recently cutting jobless aid to 19 weeks, North Carolina does not meet the threshold to receive any federal benefits.) Sequestration also cut the size of federal unemployment checks. Altogether, the federal benefits have cost about $252 billion since they began in 2008.

State governments that have reduced jobless aid say the cost of the program—and the debt they've incurred because of it—forced them to make permanent cutbacks. Overwhelmed with benefit claims during the recession, many states borrowed from the federal government when their own unemployment trust funds ran dry. Rather than tax employers more to pay for the program, states like Michigan cut back on benefits instead, and highly indebted states like California are currently weighing their choices.

Sherry Phurrough, 49, recently exhausted her state unemployment benefits in Georgia, which now offers only 18 weeks of aid. Though she's found a few weeks of temporary work, in the human resources department of a manufacturer, she worries about what's going to happen when the stint ends next month. "I'm divorced and have two kids at home," says Phurrough. "Most of us don't have a big savings account or a rich relative. I pray about my situation, and that God comes through and gives the answers."