The story of the budget in 2013 was a grand tour through the worst of Washington.

From January's fiscal cliff to October's government shutdown, attempts to make the most basic fiscal decisions produced self-destructive gridlock, brinksmanship, and the failure to even get the bare minimum accomplished.

Congress managed to leave town before Christmas without forcing us to the brink of another budget crisis, creating some hope about a new dawn of cooperation. But it was only after legislators had failed so many times in 2013 to make responsible fiscal decisions, setting their expectations at new lows.

For all the alarmism surrounding the budget this year, every fiscal crisis of 2013 was manufactured by Congress itself.

Legislators had laid the groundwork more than two years ago, passing a 2011 budget deal to reduce the deficit by $2.1 trillion: $900 billion in upfront cuts, with another $1.2 trillion that would happen in one of two ways. Either Congress could pull together a bipartisan deficit reduction deal, or automatic, across-the-board cuts called sequestration would go until effect on January 1, 2013.

Sequestration was supposed to be the sword of Damocles—a threat so great that both Republicans and Democrats would do everything in their power to keep it from ever happening. But the very first hours of 2013 made it clear that Congress would not and could not do enough to stop the vast majority of cuts.

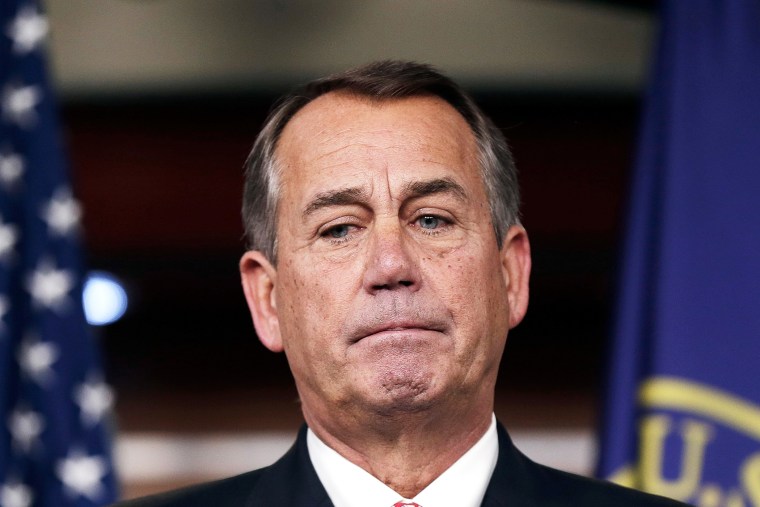

After weeks of fruitless negotiations, the Senate passed a deal around 2 a.m. on January 1 that preserved most of sequestration and the Bush tax cuts—a deal made possible only because House Speaker John Boehner broke from the majority of the GOP caucus.

The fiscal cliff deal replaced just two months of the automatic cuts and raised income taxes for Americans earning more than $750,000. It also raised taxes on the middle class by letting the payroll tax cut expire. But the bill was far from a "grand bargain" to reduce the deficit through sweeping reforms to entitlements and taxes. It raised about $600 billion in new revenue, far lower than the $1.6 trillion target that President Obama had originally set.

It was a deal born out of crisis: Boehner sided with Democrats only after he failed to get the GOP caucus to come along, and conservatives hated him for agreeing to raise taxes. And the early months of 2013 made it clear that Congress had returned to a partisan deadlock over the budget. Sen. Patty Murray and Rep. Paul Ryan drew up diametrically opposed spending plans that were $91 billion apart: Democrats proposed to reverse sequestration completely, while Republicans proposed to ramp up military spending and cut domestic programs even more sharply.

The talks between Ryan and Murray stopped altogether by the spring of 2013. And with no action from Congress, sequestration went into effect on March 1. Boehner and other Republicans blamed Obama for letting the cuts happen, dubbing it the "Obamaquester."

As the spending reductions actually took hold, however, Republicans began to change course. The White House overstated the magnitude of some of the cuts, prompting the Republicans to attack Democrats for crying wolf. Sequestration had real consequences for many other government programs, cutting Head Start programs, federal unemployment benefits, scientific research, and heating aid, with a disproportionate impact on the poor.

But the early Democratic alarmism, combined with the uneven, diffuse nature of the rolling cuts, made it difficult to gauge the overall impact of sequestration, reducing the political urgency for reversing them. And despite protestations from the GOP's defense hawks, a growing number of conservatives came to embrace sequestration as spending cuts that trimmed the fat from the government.

Knowing how much Democrats hated the automatic cuts, Boehner hoped to replace sequestration with entitlement reforms—a medium-sized bargain. But in August, an insurgent group of conservative Republicans, backed by outside pressure groups, pushed Boehner in a completely new direction: they convinced the Speaker to link the next budget deadline to the launch of Obamacare's insurance exchanges on October 1.

With Boehner's support, the anti-Obamacare campaign ultimately drove the country to a shutdown as House Republicans refused to fund the government without unraveling part of Obamacare—a total non-starter for Democrats. The shutdown stretched over 16 days, while Democrats held firm against GOP attempts to open the government piecemeal to extract an Obamacare concession. It ended when the GOP leadership finally admitted its campaign was doomed to fail, voting with Democrats to keep the government running and raise the debt ceiling without any pre-conditions.

Ordinary Americans hated the shutdown and overwhelmingly blamed Republicans for a self-inflicted wound that cost the country billions of dollars. The experience prompted the GOP to take a more pragmatic stance toward the budget, helping to clear the way for a modest bipartisan budget deal that easily passed the House and Senate a few weeks later.

But the compromise came only after both parties had seriously ratcheted down their expectations. The deal reversed just one-third of sequestration's cuts in 2014-15 without accomplishing any of the goals that both Democrats and Republicans had set out for themselves two and a half years earlier.

All that fiscal brinksmanship barely touched the major tax and entitlement programs that are the biggest drivers of the budget. Instead, Congress's austerity project slashed trillions in discretionary programs, undermining programs that both parties support while doing little to reduce the long-term deficit. Democrats got $600 billion in additional tax revenue from January's fiscal cliff deal, but the tax changes did nothing to address the fundamental problems with our antiquated tax code.

Having failed to meet its own expectations so many times already—hurting economic confidence and shaking the public's faith in the process—Congress resigned itself to doing the minimum possible to keep the government running. And even that is no guarantee.

Though Congress seems to have reached a detente over the budget, to avoid another government shutdown, legislators still need to decide how they'll spend the money before January 15, which could spur fights over funding for environmental programs, the IRS, Obamacare, and other flashpoints.

Then Congress will have to raise the debt ceiling once again, which has already prompted Republicans like Ryan to demand concessions that Democrats refuse to make. So 2014 could still mean a return of the fiscal brinksmanship that's left so many Americans disgusted with Washington.